- HOME

- SOLDIER RESEARCH

- WOLVERTONS AMATEUR MILITARY TRADITION

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE RIFLE VOLUNTEERS 1859-1908

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BATTALION 1908-1947

- The Bucks Battalion A Brief History

- REGIMENTAL MARCH

-

1ST BUCKS 1914-1919

>

- 1914-15 1/1ST BUCKS MOBILISATION

- 1915 1/1ST BUCKS PLOEGSTEERT

- 1915-16 1/1st BUCKS HEBUTERNE

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS SOMME JULY 1916

- 1916 1/1st BUCKS POZIERES WAR DIARY 17-25 JULY

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS SOMME AUGUST 1916

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS LE SARS TO CAPPY

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS THE GERMAN RETIREMENT

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS TOMBOIS FARM

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS THE HINDENBURG LINE

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS 3RD BATTLE OF YPRES

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES 16th AUGUST

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES WAR DIARY 15-17 JULY

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS 3RD BATTLE OF YPRES - VIMY

- 1917-18 1/1ST BUCKS ITALY

-

2ND BUCKS 1914-1918

>

- 1914-1916 2ND BUCKS FORMATION & TRAINING

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS ARRIVAL IN FRANCE

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS FROMELLES

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS REORGANISATION

- 1916-1917 2/1st BUCKS THE SOMME

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS THE GERMAN RETIREMENT

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS ST QUENTIN APRIL TO AUGUST 1917

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS ARRAS & CAMBRAI

- 1918 2/1st BUCKS ST QUENTIN TO DISBANDMENT

-

1ST BUCKS 1939-1945

>

- 1939-1940 1BUCKS MOBILISATION & NEWBURY

- 1940 1BUCKS FRANCE & BELGIUM

- 1940 1BUCKS HAZEBROUCK

- HAZEBROUCK BATTLEFIELD VISIT

- 1940-1942 1BUCKS

- 1943-1944 1BUCKS PREPARING FOR D DAY

- COMPOSITION & ROLE OF BEACH GROUP

- BROAD OUTLINE OF OPERATION OVERLORD

- 1944 1ST BUCKS NORMANDY D DAY

- 1944 1BUCKS 1944 NORMANDY TO BRUSSELS (LOC)

- Sword Beach Gallery

- 1945 1BUCKS 1945 FEBRUARY-JUNE T FORCE 1st (CDN) ARMY

- 1945 1BUCKS 1945 FEBRUARY-JUNE T FORCE 2ND BRITISH ARMY

- 1945 1BUCKS JUNE 1945 TO AUGUST 1946

- BUCKS BATTALION BADGES

- BUCKS BATTALION SHOULDER TITLES 1908-1946

- 1939-1945 BUCKS BATTALION DRESS >

- ROYAL BUCKS KINGS OWN MILITIA

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE'S LINE REGIMENTS

- ROYAL GREEN JACKETS

- OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1965

- OXF & BUCKS LI INSIGNIA >

- REGIMENTAL CUSTOMS & TRADITIONS >

- REGIMENTAL COLLECT AND PRAYER

- OXF & BUCKS LI REGIMENTAL MARCHES

- REGIMENTAL DRILL >

-

REGIMENTAL DRESS

>

- REGIMENTAL UNIFORM 1741-1896

- REGIMENTAL UNIFORM 1741-1914

- 1894 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1897 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1900 DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1931 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1939-1945 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1950 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1960 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS (TA)

- 1960 REGIMENTAL MESS DRESS

- 1963 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1958-1969 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- HEADDRESS >

- REGIMENTAL CREST

- BATTLE HONOURS

- REGIMENTAL COLOURS >

- BRIEF HISTORY

- REGIMENTAL CHAPEL, OXFORD >

-

THE GREAT WAR 1914-1918

>

- REGIMENTAL BATTLE HONOURS 1914-1919

- OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY INTRODUCTION

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY

- 1/4 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 2/4 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 1/1 BUCKS BATTALION 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 2/1 BUCKS BATTALION 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 5 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 6 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 7 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 8 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 1st GREEN JACKETS (43rd & 52nd) 1958-1965

- 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND) 1958-1965

- 1959 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1959 REGIMENTAL MARCH IN OXFORD

- 1959 DEMONSTRATION BATTALION

- 1960 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1961 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1961 THE LONGEST DAY

- 1962 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1963 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1963 CONVERSION TO “RIFLE” REGIMENT

- 1964 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1965 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1965 FORMATION OF ROYAL GREEN JACKETS

- REGULAR BATTALIONS 1741-1958

-

1st BATTALION (43rd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

-

43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1914

>

- 43rd REGIMENT 1741-1802

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1803-1805

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1806-1809

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1809-1810

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1810-1812

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1812-1814

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1814-1818

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1818-1854

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1854-1863

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1863-1865

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1865-1897

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1899-1902

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1902-1914

-

1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919

>

-

1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1920-1939

>

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1920

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1921

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1922

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1923

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1924

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1925

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1926

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1927

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1928

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1929

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1930

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1931

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1932

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1933

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1934

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1935

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1936

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1937

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1938

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1939

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945 >

-

1 OXF & BUCKS 1946-1958

>

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1946

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1947

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1948

- 1948 FREEDOM PARADES

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1949

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1950

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1951

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1952

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1953

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1954

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1955

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1956

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1957

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1958

-

43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1914

>

-

2nd BATTALION (52nd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

- 52nd LIGHT INFANTRY 1755-1881 >

- 2 OXF LI 1881-1907

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1908-1914

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919

>

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919-1939

>

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1920

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1921

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1922

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1923

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1924

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1925

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1926

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1927

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1928

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1929

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1930

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1931

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1932

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1933

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1934

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1935

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1936

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1937

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1938

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1939

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945

>

- 1939-1941

- 1941-1943 AIRBORNE INFANTRY

- 1944 PREPARATION FOR D DAY

- 1944 PEGASUS BRIDGE-COUP DE MAIN

- Pegasus Bridge Gallery

- Horsa Bridge Gallery

- COUP DE MAIN NOMINAL ROLL

- MAJOR HOWARDS ORDERS

- 1944 JUNE 6

- D DAY ORDERS

- 1944 JUNE 7-13 ESCOVILLE & HEROUVILETTE

- Escoville & Herouvillette Gallery

- 1944 JUNE 13-AUGUST 16 HOLDING THE BRIDGEHEAD

- 1944 AUGUST 17-31 "PADDLE" TO THE SEINE

- "Paddle To The Seine" Gallery

- 1944 SEPTEMBER ARNHEM

- OPERATION PEGASUS 1

- 1944/45 ARDENNES

- 1945 RHINE CROSSING

- OPERATION VARSITY - ORDERS

- OPERATION VARSITY BATTLEFIELD VISIT

- 1945 MARCH-JUNE

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI DRESS 1940-1945 >

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1946-1947 >

-

1st BATTALION (43rd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

- MILITIA BATTALIONS

- TERRITORIAL BATTALIONS

- WAR RAISED/SERVICE BATTALIONS 1914-18 & 1939-45

-

5th, 6th, 7th & 8th (SERVICE) 1914-1918

>

-

6th & 7th Bns OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945

>

- 6th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI 1940-1945 >

-

7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI 1940-1945

>

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1940-JULY 1942

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JULY 1942 – JUNE 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JULY 1943–OCTOBER 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI OCTOBER 1943–DECEMBER 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI DECEMBER 1943-JUNE 1944

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JANUARY 1944-JUNE 1944

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1944–JANUARY 1945

-

5th, 6th, 7th & 8th (SERVICE) 1914-1918

>

- "IN MY OWN WORDS"

- CREDITS

MAJOR Allison Digby TATHAM WARTER D.S.O.

Officer Commanding A Company

2nd Parachute Battalion

Commissioned into the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry in 1938. He served with the 2nd Battalion (52nd) then in India. He returned to the UK from India with the 52nd in 1940 and went on to command Letter C Company.

By 1942 the 52nd were a glider-borne Battalion. This was not exciting enough for Tatham-Warter, however, and in 1943 he joined the Parachute Regiment. He was given command of “A” Company of the 2nd Parachute Battalion who he would lead at Arnhem.

When training his Company in the UK and remembering his Light Infantry roots, Major Tatham-Warter concerned about the effectiveness of radios had set up a system of using Bugles to send signals within his company that were used to good effect on the march to the bridge and in its defence.

The umbrella wielding officer in the film “A Bridge Too Far” is based on Major Tatham-Warter who carried his umbrella because he could not remember the password. There are reports that on one occasion he used the rolled-up umbrella to disable a German armoured car, simply by thrusting it through an observation slit in the vehicle and incapacitating the driver!

On another occasion during a mortar bombardment the Battalion padre, Father Egan, was trying to cross to a building on the other side of the street to visit the wounded in its cellar. He made an attempt to move over but was forced to seek shelter from intense mortar fire. He then noticed Digby Tatham-Warter casually approaching him. The Major opened his old and battered umbrella and held it over Egan's head, beckoning him "Come on, Padre". Egan drew Tatham-Warter's attention to all the mortars exploding everywhere, to which came the reply "Don't worry, I've got an umbrella."

Brigadier (later General Sir Gerald) Lathbury recalled that Tatham-Warter took command of 2 Para “when the Colonel was seriously wounded and the second-in-command killed ... He did a magnificent job, moving around the district freely and was so cool that on one occasion he arrived at the door of a house simultaneously with two German soldiers - and allowed them to stand back to let him go in first.”

After the defence at the bridge ended, Major Tatham-Warter was taken away with the wounded of the battalion but along with his Company 2ic he managed to escape from hospital and with the help of the Dutch underground managed to evade capture and after the withdrawal of the remnants of the Division across the Rhine at the end of the battle he was involved in organising many of the evading Airborne troops left behind to get back to Allied lines in “Operation Pegasus”.

By 1942 the 52nd were a glider-borne Battalion. This was not exciting enough for Tatham-Warter, however, and in 1943 he joined the Parachute Regiment. He was given command of “A” Company of the 2nd Parachute Battalion who he would lead at Arnhem.

When training his Company in the UK and remembering his Light Infantry roots, Major Tatham-Warter concerned about the effectiveness of radios had set up a system of using Bugles to send signals within his company that were used to good effect on the march to the bridge and in its defence.

The umbrella wielding officer in the film “A Bridge Too Far” is based on Major Tatham-Warter who carried his umbrella because he could not remember the password. There are reports that on one occasion he used the rolled-up umbrella to disable a German armoured car, simply by thrusting it through an observation slit in the vehicle and incapacitating the driver!

On another occasion during a mortar bombardment the Battalion padre, Father Egan, was trying to cross to a building on the other side of the street to visit the wounded in its cellar. He made an attempt to move over but was forced to seek shelter from intense mortar fire. He then noticed Digby Tatham-Warter casually approaching him. The Major opened his old and battered umbrella and held it over Egan's head, beckoning him "Come on, Padre". Egan drew Tatham-Warter's attention to all the mortars exploding everywhere, to which came the reply "Don't worry, I've got an umbrella."

Brigadier (later General Sir Gerald) Lathbury recalled that Tatham-Warter took command of 2 Para “when the Colonel was seriously wounded and the second-in-command killed ... He did a magnificent job, moving around the district freely and was so cool that on one occasion he arrived at the door of a house simultaneously with two German soldiers - and allowed them to stand back to let him go in first.”

After the defence at the bridge ended, Major Tatham-Warter was taken away with the wounded of the battalion but along with his Company 2ic he managed to escape from hospital and with the help of the Dutch underground managed to evade capture and after the withdrawal of the remnants of the Division across the Rhine at the end of the battle he was involved in organising many of the evading Airborne troops left behind to get back to Allied lines in “Operation Pegasus”.

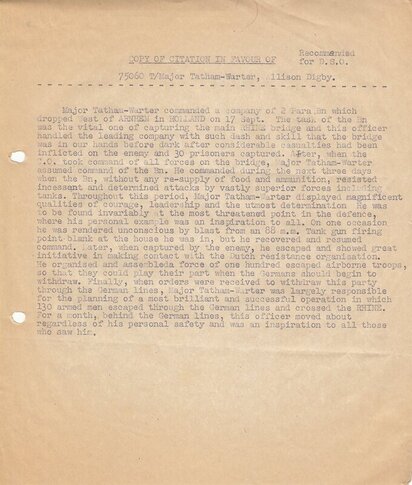

For his exploits at Arnhem and beyond he was awarded the

DISTINGUISHED SERVICE ORDER for:

“Major Tatham-Warter commanded a company of 2 Para Bn which dropped west of ARNHEM in HOLLAND on 17 Sept.

The task of the Bn was the vital one of capturing the main RHINE bridge and this officer handled the leading company with such dash and skill that the bridge was in our hands before dark after considerable casualties had been inflicted on the enemy and 30 prisoners captured. After, when the O.C. took command of all forces on the bridge, Major Tatham-Warter assumed command of the Bn. He commanded during the next three days when the Bn, without any re-supply of food and ammunition, resisted incessant and determined attacks by vastly superior forces including tanks. Throughout this period, Major Tatham-Warter displayed magnificent qualities of courage, leadership and the utmost determination. He was to be found invariably at the most threatened point in the defence, where his personal example was an inspiration to all. On one occasion he was rendered unconscious by blast from an 88m.m. Tank gun firing point-blank at the house he was in, but he recovered and resumed command.

Later, when captured by the enemy, he escaped and showed great initiative in making contact with the Dutch resistance organisation.

He organised and assembled a force of one hundred escaped airborne troops, so that they could play their part when the Germans should begin to withdraw.

Finally, when orders were received to withdraw this party through the German lines, Major Tatham-Warter was largely responsible for the planning of a most brilliant and successful operation in which 130 armed men escaped through the German lines and crossed the RHINE.

For a month, behind the German lines, this officer moved about regardless of his personal safety and was an inspiration to all those who saw him.”

OBITUARY NOTICE EXTRACT FROM THE ROYAL GREEN JACKETS REGIMENTAL CHRONICLE 1993.

MAJOR A.D. DIGBY TATHAM-WARTER, DSO

The Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

Digby Tatham-Warter, former company commander, in the 52nd and in 2nd Battalion, Parachute Regiment, who has died aged 75, was celebrated for leading a bayonet charge at Arnhem in September 1944, sporting an old bowler hat and with a tattered umbrella.

During the long, bitter conflict Tatham-Warter strolled around nonchalantly during the heaviest fire. The padre (Fr Egan) recalled that, while he was trying to make his way to visit some wounded in the cellars and had taken temporary shelter from enemy fire Tatham-Waiter came up to him, and said: "Don't worry about the bullets: I've got an umbrella."

Having escorted the padre under his brolly, Tatham-Warter continued visiting the men who were holding the perimeter defences. "That thing won't do you much good," commented one of his fellow officers, to which Tatham-Warter replied: "But what if it rains?"

By that stage in the battle all hope of being relieved by the arrival of 30 Corps had vanished. The Germans were pounding the beleaguered airborne forces with heavy artillery and fire from Tiger tanks, so that most of the houses were burning and the area was littered with dead and wounded.

But German suggestions that the parachutists should surrender received a rude response. Tatham-Warter's umbrella became a symbol of defiance, as the British, although short of ammunition, food and water, stubbornly held on to the north end of the road bridge.

Arnhem was the furthest ahead of three bridges in Holland which the Allies needed to seize if they were going to outflank the Siegfried line. Securing the bridge by an airborne operation would enable 30 Corps to cross the Rhine and press on into Germany.

As the first V2 rocket had fallen in Britain earlier that month, speed in winning the land battle in Europe was essential. In the event, however, the parachutists were dropped unnecessarily far from the bridge, and the lightly-armed Airborne Division was attacked by two German Panzer divisions whose presence in the area had not been realised: soldiers from one of them reached the bridge before the British parachutists. Tatham-Warter and his men therefore had to fight their way to the bridge, capture the north end, try to cross it and capture the other side. This they failed to do.

At one point the back of Tatham-Warter's trouserings was whipped out by blast, giving him a vaguely scarecrow-like appearance instead of his normally immaculate turnout. Eventually he was wounded (as was the padre), and consigned to a hospital occupied by the Germans. Although his wound was not serious Tatham-Warter realised that he had a better chance of escape if he stayed with the stretcher cases. During the night, with his more severely wounded second-in-command (Capt A.M. Frank), he crawled out of the hospital window and reached "a very brave lone Dutch woman" who took them in and hid them. She spoke no English and was very frightened, but fed them and put them in touch with a neighbour who disguised them as house painters and sheltered them in a delivery van, from where they moved to a house.

Tatham-Warter then bicycled around the countryside, which was full of Germans, making contact with other Arnhem escapees (called evaders) and informing them of the rendezvous for an escape over the Rhine. On one of these trips, he and his companion were overtaken by a German staff car, which skidded off the muddy road into a ditch. "As the officers seemed to be in an excitable state," he recalled, "we thought it wise to help push their car out and back on to the road. They were gracious enough to thank us for our help."

As jobbing painters, Tatham-Warter and Frank aroused no suspicions by their presence in the home of the Wildeboer family (who owned a paint factory), although the area abounded with Gestapo, Dutch SS and collaborators. Even when four Panzer soldiers were billeted on the Wildeboers, they merely nodded and greeted each other on their comings and goings.

Eventually, with the help of the Dutch Resistance, Tatham-Warter assembled an escape party of 150, which included shot-down airmen and even two Russians. Guided by the Dutch, they found their way through the German lines, often passing within a few yards of German sentries and outposts. Tatham-Warter suspected that the Germans deliberately failed to hear them: 30 Corps had been sending over strong fighting patrols of American parachutists temporarily under their command, and the Germans had no stomach for another bruising encounter.

In spite of Tatham-Warter's stern admonitions, he recalled that his party sounded more like a herd of buffaloes than a secret escape party. Finally, they reached the river bank where they were ferried over by British sappers from 30 Corps and met by Hugh Fraser (then in the SAS) and Airey Neave, who had been organising their escape.

Tatham-Warter was awarded the DSO after the battle.

Allison Digby Tatham-Warter was born on May 26 1917 and educated at Wellington and Sandhurst. He was destined for the Indian Army but while on the statutory year of attachment to an English regiment in India - in this case the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry - he liked it so much that he decided to stay on. He formally transferred to the regiment in 1938.

He had ample opportunity for pig-sticking: on one occasion he killed three wild boar while hunting alone. The average weight of the boars was 150 Ib and their height 32 in. He also took up polo - which he called "snobs' hockey" - with considerable success.

In 1939 he shot a tiger when on foot. With a few friends he had gone to the edge of the jungle to make arrangements for the reception of a tiger the next evening. As they were doing so, they suddenly noticed that one had arrived prematurely. They shinned up the nearest trees, accompanied by some equally prudent monkeys. When the monkeys decided it was safe to descend, the party followed, only to find that the tiger was once more with them. This time Tatham-Warter, who was nearest, was ready, but it was a close shave.

In 1942 the 52nd were a glider-borne Battalion. This was not exciting enough for Tatham-Warter, however, and in 1944 he joined the Parachute Regiment. "He was lusting for action at that time", John Frost (later Major-General) recalled of Tatham-Warter, "having so far failed to get into the war. There was much of 'Prince Rupert' about Digby and he was worth a bet with anybody's money."

Tatham-Warter's striking appearance was particularly valuable when the British were fighting against impossible odds at Arnhem. For within the perimeter were soldiers from other detachments, signals, sappers and gunners, who would not know him by sight as his own men would, but who could not fail to be inspired by his towering figure and unflagging spirit of resistance.

Brigadier (later Gen Sir Gerald) Lathbury recalled that Tatham-Warter took command of 2 Para "when the Colonel was seriously wounded and the second-in-command killed ... He did a magnificent job, moving around the district freely and was so cool that on one occasion he arrived at the door of a house simultaneously with two German soldiers - and allowed them to stand back to let him go in first.

In Sir Richard Attenborough's controversial film about Arnhem, A Bridge Too Far, the character based on Tatham-Warter was played by Christopher Good.

In 1991 Digby Tatham-Warter published his own recollections, "Dutch Courage and Pegasus", which described his escape after Arnhem and paid tribute to the Dutch civilians who had helped him. He often revisited them.

He married, in 1949, Jane Boyd; they had three daughters.

By kind permission of the Daily Telegraph 30/3/93

R.H-W. Writes

The larger world will remember Digby for his courage and individual style at Arnhem, and for the escape afterwards in which he played so prominent a part. Much has been written elsewhere about that epic battle and its aftermath including Digby's own excellent memoir - modestly told after endless persuasion. The smaller world of his innumerable friends and acquaintances will remember his personal magnetism, his outspoken comments on men and affairs, his loyalty and kindness, often disguised under a sometimes irascible and impatient manner. Many memorable stories of him will be swapped over the dinner tables of his friends in years to come.

Digby was, above all, a born leader with acute intelligence, a marked capacity for meticulous planning and organisation, and great charm. He could have risen far, but had little worldly ambition.

I first served with him in the 52nd in India in 1937, and was to see much of him and his family at intervals over the year. He was soon recognised as an excellent regimental officer, and an enthusiastic sportsman of great promise, an outstanding horseman and horse-master, equally at home with a rod or gun.

I was to serve with him again in the 5th King's African Rifles in Kenya in 1946. There he immediately scraped together a pack of hounds, tried without success to introduce pig-sticking - a sport in which he had excelled in India, resumed playing polo, shot and fished whenever possible.

Loving Kenya he decided to retire in 1948 to a modest farm at Eburru overlooking the Rift valley. He was never a rich man as many thought. Perhaps his "presence", always immaculate, and lavish style led to that belief. Soon he had the good fortune to marry Jane Boyd, who not only embodies all the graces and is a wonderful hostess, but shared many of his interests.

Their busy farming and social life was to be interrupted in 1952 by the Mau Mau emergency. Digby, perceptive as ever, realised the value of a horsed unit in the prevailing conditions. With the necessary permission he formed and commanded the mounted section of the Kenya Police Reserve recruited from young farmers with their own horses, "syces" and trackers, reinforced by some expatriate volunteers - all great individualists. This was a natural for Digby (shades of the cavalry for which he was originally destined) and they soon became, under his leadership, a very effective unit contributing significantly to the resolution of the emergency.

Normal life was resumed with Jane and their small daughters, Caroline, Joanna and Belinda. Digby had become a leading light in the horse world; Captain of the Kenya International Polo team (personal handicap 6); President of the Kenya Horse Society; judge at horse shows and organiser of Pony Club camps. Particularly good with young people, there are many now grown who gratefully acknowledge the part he played in their development with his sharp ways, encouragement and guidance pushing them to limits they never expected to reach. They loved him and were putty in his hands.

He now found it politic to sell the Eburru farm and move to a small ranch near Nanyuki. Here with school bills mounting he looked for an additional source of income and found it, collaborating with Colonel Hilary Hook, in the developing photographic safari market where there was a demand for safaris tailored to family parties or small groups of friends. Digby's tented camps were luxurious and the food and amenities second to none. Both Digby and Jane loved the life to which they were so well suited with their extensive knowledge of the country, its wildlife, and not least their personalities. The venture was an almost immediate success and their clients, many rich Americans amongst them, were to become great friends who would return in succeeding years. Off-seasons were increasingly punctuated by visits to the coast to cruise and fish for marlin and other game fish.

Their houses through all these years were a haven for many and usually filled with guests (none more welcome than old, and new, friends from his regiments and the army). Their hospitality was legendary, perfect meals and never a dull moment or empty glass; much lively conversation, verbal sparring, and laughter. Sometimes late in the evening conversation would become contentious and a close friend might be told "never to darken his doorstep again". All this was well understood and immediately forgotten.

Ill-health forced Digby to abandon safaris and turn to something less strenuous developing his skill at carpentry into making fine furniture and small exquisite inlaid boxes of professional quality. His artistic feeling showed itself in other ways. He delighted in designing and redesigning the three beautiful gardens they created. Jane providing the green fingers and know-how.

Increasingly disabled and ultimately bed-ridden he never lost his sense of humour or intense curiosity in all things great and small. A familiar glint would come into his eye when anything particularly amused or annoyed him.

He was indeed remarkable. Something of a legend in his own time, a life-enhancer and man of action who filled every unforgiving minute. He leaves a void in many lives especially, of course, in Jane's and their exceptionally close-knit family now including eight grandchildren.

Sadly the name dies with him but will not be forgotten.

MAJOR A.D. DIGBY TATHAM-WARTER, DSO

The Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

Digby Tatham-Warter, former company commander, in the 52nd and in 2nd Battalion, Parachute Regiment, who has died aged 75, was celebrated for leading a bayonet charge at Arnhem in September 1944, sporting an old bowler hat and with a tattered umbrella.

During the long, bitter conflict Tatham-Warter strolled around nonchalantly during the heaviest fire. The padre (Fr Egan) recalled that, while he was trying to make his way to visit some wounded in the cellars and had taken temporary shelter from enemy fire Tatham-Waiter came up to him, and said: "Don't worry about the bullets: I've got an umbrella."

Having escorted the padre under his brolly, Tatham-Warter continued visiting the men who were holding the perimeter defences. "That thing won't do you much good," commented one of his fellow officers, to which Tatham-Warter replied: "But what if it rains?"

By that stage in the battle all hope of being relieved by the arrival of 30 Corps had vanished. The Germans were pounding the beleaguered airborne forces with heavy artillery and fire from Tiger tanks, so that most of the houses were burning and the area was littered with dead and wounded.

But German suggestions that the parachutists should surrender received a rude response. Tatham-Warter's umbrella became a symbol of defiance, as the British, although short of ammunition, food and water, stubbornly held on to the north end of the road bridge.

Arnhem was the furthest ahead of three bridges in Holland which the Allies needed to seize if they were going to outflank the Siegfried line. Securing the bridge by an airborne operation would enable 30 Corps to cross the Rhine and press on into Germany.

As the first V2 rocket had fallen in Britain earlier that month, speed in winning the land battle in Europe was essential. In the event, however, the parachutists were dropped unnecessarily far from the bridge, and the lightly-armed Airborne Division was attacked by two German Panzer divisions whose presence in the area had not been realised: soldiers from one of them reached the bridge before the British parachutists. Tatham-Warter and his men therefore had to fight their way to the bridge, capture the north end, try to cross it and capture the other side. This they failed to do.

At one point the back of Tatham-Warter's trouserings was whipped out by blast, giving him a vaguely scarecrow-like appearance instead of his normally immaculate turnout. Eventually he was wounded (as was the padre), and consigned to a hospital occupied by the Germans. Although his wound was not serious Tatham-Warter realised that he had a better chance of escape if he stayed with the stretcher cases. During the night, with his more severely wounded second-in-command (Capt A.M. Frank), he crawled out of the hospital window and reached "a very brave lone Dutch woman" who took them in and hid them. She spoke no English and was very frightened, but fed them and put them in touch with a neighbour who disguised them as house painters and sheltered them in a delivery van, from where they moved to a house.

Tatham-Warter then bicycled around the countryside, which was full of Germans, making contact with other Arnhem escapees (called evaders) and informing them of the rendezvous for an escape over the Rhine. On one of these trips, he and his companion were overtaken by a German staff car, which skidded off the muddy road into a ditch. "As the officers seemed to be in an excitable state," he recalled, "we thought it wise to help push their car out and back on to the road. They were gracious enough to thank us for our help."

As jobbing painters, Tatham-Warter and Frank aroused no suspicions by their presence in the home of the Wildeboer family (who owned a paint factory), although the area abounded with Gestapo, Dutch SS and collaborators. Even when four Panzer soldiers were billeted on the Wildeboers, they merely nodded and greeted each other on their comings and goings.

Eventually, with the help of the Dutch Resistance, Tatham-Warter assembled an escape party of 150, which included shot-down airmen and even two Russians. Guided by the Dutch, they found their way through the German lines, often passing within a few yards of German sentries and outposts. Tatham-Warter suspected that the Germans deliberately failed to hear them: 30 Corps had been sending over strong fighting patrols of American parachutists temporarily under their command, and the Germans had no stomach for another bruising encounter.

In spite of Tatham-Warter's stern admonitions, he recalled that his party sounded more like a herd of buffaloes than a secret escape party. Finally, they reached the river bank where they were ferried over by British sappers from 30 Corps and met by Hugh Fraser (then in the SAS) and Airey Neave, who had been organising their escape.

Tatham-Warter was awarded the DSO after the battle.

Allison Digby Tatham-Warter was born on May 26 1917 and educated at Wellington and Sandhurst. He was destined for the Indian Army but while on the statutory year of attachment to an English regiment in India - in this case the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry - he liked it so much that he decided to stay on. He formally transferred to the regiment in 1938.

He had ample opportunity for pig-sticking: on one occasion he killed three wild boar while hunting alone. The average weight of the boars was 150 Ib and their height 32 in. He also took up polo - which he called "snobs' hockey" - with considerable success.

In 1939 he shot a tiger when on foot. With a few friends he had gone to the edge of the jungle to make arrangements for the reception of a tiger the next evening. As they were doing so, they suddenly noticed that one had arrived prematurely. They shinned up the nearest trees, accompanied by some equally prudent monkeys. When the monkeys decided it was safe to descend, the party followed, only to find that the tiger was once more with them. This time Tatham-Warter, who was nearest, was ready, but it was a close shave.

In 1942 the 52nd were a glider-borne Battalion. This was not exciting enough for Tatham-Warter, however, and in 1944 he joined the Parachute Regiment. "He was lusting for action at that time", John Frost (later Major-General) recalled of Tatham-Warter, "having so far failed to get into the war. There was much of 'Prince Rupert' about Digby and he was worth a bet with anybody's money."

Tatham-Warter's striking appearance was particularly valuable when the British were fighting against impossible odds at Arnhem. For within the perimeter were soldiers from other detachments, signals, sappers and gunners, who would not know him by sight as his own men would, but who could not fail to be inspired by his towering figure and unflagging spirit of resistance.

Brigadier (later Gen Sir Gerald) Lathbury recalled that Tatham-Warter took command of 2 Para "when the Colonel was seriously wounded and the second-in-command killed ... He did a magnificent job, moving around the district freely and was so cool that on one occasion he arrived at the door of a house simultaneously with two German soldiers - and allowed them to stand back to let him go in first.

In Sir Richard Attenborough's controversial film about Arnhem, A Bridge Too Far, the character based on Tatham-Warter was played by Christopher Good.

In 1991 Digby Tatham-Warter published his own recollections, "Dutch Courage and Pegasus", which described his escape after Arnhem and paid tribute to the Dutch civilians who had helped him. He often revisited them.

He married, in 1949, Jane Boyd; they had three daughters.

By kind permission of the Daily Telegraph 30/3/93

R.H-W. Writes

The larger world will remember Digby for his courage and individual style at Arnhem, and for the escape afterwards in which he played so prominent a part. Much has been written elsewhere about that epic battle and its aftermath including Digby's own excellent memoir - modestly told after endless persuasion. The smaller world of his innumerable friends and acquaintances will remember his personal magnetism, his outspoken comments on men and affairs, his loyalty and kindness, often disguised under a sometimes irascible and impatient manner. Many memorable stories of him will be swapped over the dinner tables of his friends in years to come.

Digby was, above all, a born leader with acute intelligence, a marked capacity for meticulous planning and organisation, and great charm. He could have risen far, but had little worldly ambition.

I first served with him in the 52nd in India in 1937, and was to see much of him and his family at intervals over the year. He was soon recognised as an excellent regimental officer, and an enthusiastic sportsman of great promise, an outstanding horseman and horse-master, equally at home with a rod or gun.

I was to serve with him again in the 5th King's African Rifles in Kenya in 1946. There he immediately scraped together a pack of hounds, tried without success to introduce pig-sticking - a sport in which he had excelled in India, resumed playing polo, shot and fished whenever possible.

Loving Kenya he decided to retire in 1948 to a modest farm at Eburru overlooking the Rift valley. He was never a rich man as many thought. Perhaps his "presence", always immaculate, and lavish style led to that belief. Soon he had the good fortune to marry Jane Boyd, who not only embodies all the graces and is a wonderful hostess, but shared many of his interests.

Their busy farming and social life was to be interrupted in 1952 by the Mau Mau emergency. Digby, perceptive as ever, realised the value of a horsed unit in the prevailing conditions. With the necessary permission he formed and commanded the mounted section of the Kenya Police Reserve recruited from young farmers with their own horses, "syces" and trackers, reinforced by some expatriate volunteers - all great individualists. This was a natural for Digby (shades of the cavalry for which he was originally destined) and they soon became, under his leadership, a very effective unit contributing significantly to the resolution of the emergency.

Normal life was resumed with Jane and their small daughters, Caroline, Joanna and Belinda. Digby had become a leading light in the horse world; Captain of the Kenya International Polo team (personal handicap 6); President of the Kenya Horse Society; judge at horse shows and organiser of Pony Club camps. Particularly good with young people, there are many now grown who gratefully acknowledge the part he played in their development with his sharp ways, encouragement and guidance pushing them to limits they never expected to reach. They loved him and were putty in his hands.

He now found it politic to sell the Eburru farm and move to a small ranch near Nanyuki. Here with school bills mounting he looked for an additional source of income and found it, collaborating with Colonel Hilary Hook, in the developing photographic safari market where there was a demand for safaris tailored to family parties or small groups of friends. Digby's tented camps were luxurious and the food and amenities second to none. Both Digby and Jane loved the life to which they were so well suited with their extensive knowledge of the country, its wildlife, and not least their personalities. The venture was an almost immediate success and their clients, many rich Americans amongst them, were to become great friends who would return in succeeding years. Off-seasons were increasingly punctuated by visits to the coast to cruise and fish for marlin and other game fish.

Their houses through all these years were a haven for many and usually filled with guests (none more welcome than old, and new, friends from his regiments and the army). Their hospitality was legendary, perfect meals and never a dull moment or empty glass; much lively conversation, verbal sparring, and laughter. Sometimes late in the evening conversation would become contentious and a close friend might be told "never to darken his doorstep again". All this was well understood and immediately forgotten.

Ill-health forced Digby to abandon safaris and turn to something less strenuous developing his skill at carpentry into making fine furniture and small exquisite inlaid boxes of professional quality. His artistic feeling showed itself in other ways. He delighted in designing and redesigning the three beautiful gardens they created. Jane providing the green fingers and know-how.

Increasingly disabled and ultimately bed-ridden he never lost his sense of humour or intense curiosity in all things great and small. A familiar glint would come into his eye when anything particularly amused or annoyed him.

He was indeed remarkable. Something of a legend in his own time, a life-enhancer and man of action who filled every unforgiving minute. He leaves a void in many lives especially, of course, in Jane's and their exceptionally close-knit family now including eight grandchildren.

Sadly the name dies with him but will not be forgotten.

EXTRACT FROM THE REGIMENTAL CHRONICLE OF THE

OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY 1946

ESCAPE FROM ARNHEM

BY MAJOR A. D. TATHAM-WARTER, D.S.O.

The story of my escape after the Battle of Arnhem is bound up with that of so many others and with so many minor incidents, some of them quite fantastic, that a book would be required to tell it properly. I shall therefore have to concentrate on the simple story and leave out a great deal that would make it more interesting.

The battle at the bridge ended disastrously, as is well known, after four days fighting. Tony Franks and I were taken to a German hospital on the outskirts of the town. We intended to make our stay as short as possible, and after dark dressed ourselves between visits by the orderlies and climbed out of the window, crawled through the garden, past the guards and into a pine wood. Tony still had a piece of shrapnel in his ankle and I was fairly battered so we did not expect to get far that night. Added to this we had no maps and only our escape outfit button compass. This proved a godsend and we moved on it in a westerly direction through the western suburbs of Arnhem with no immediate plan other than to find shelter and food which we hadn't seen for over two days. Daylight found us at a farm a mile from Arnhem.

We were obliged to take the chance of it being occupied and knocked on the door. A friendly but very frightened woman greeted us, hid us in a loft and fed us on eggs and cheese. Later on in the morning she introduced a house decorator who had been educated in America and seemed delighted to take care of us.

He tried to move us that day, but after two narrow shaves, hid us in a woodpile on the farm for the night. The next day he led us, disguised as his sons, to his own house, and there we stayed for a week. The courage of this man, his family and many like them cannot be too highly praised. There were Germans in the area all the time, many coming to the house. The penalty if we were found was death for the whole family. This penalty had been carried out in other instances.

While we hid there, amusing ourselves by cutting home grown tobacco leaves, with scissors, to smoke, word was brought in of a wounded General hiding nearby. An exchange of notes showed this to be Gerald Lathbury, recovering from a bad wound. This put new heart into us, and when a representative of the Resistance organization of Ede, a town ten miles to the west, came over to ask for our assistance, I decided to go with him. To cut the story short, I cycled over with my new friend, leaving Tony and the Brigadier, who were not fit for this kind of travel, with a promise to arrange for them to join me later. The journey had to be made in daylight as the night curfew was strictly enforced. It was quite uneventful, though we passed several hundred Germans on the road.

I was taken straight to the Underground Headquarters and introduced. Thence to a tailor, who gave me a new suit of clothes; to a photographer who provided me with an identity card, and finally a haircut. I was now considered sufficiently Dutch to move freely about the town and countryside, but always with an escort to answer awkward questions if the need arose.

My identity card showed me to be the deaf and dumb son of a lawyer in The Hague. I lived now with 'Bill', the leader of this Resistance Group, until our final escape nearly three weeks later. He was a most remarkable character, with a lovable and forceful personality that nothing disturbed, and which kept his district active long after most of the Resistance Groups had been broken up by the Gestapo,

Three days later Gerald Lathbury and Tony were brought over by car and established in houses in the town. Gerald's house overlooked the main square which had been turned into a 'REME' workshops, where he had the opportunity of studying the Boche mechanics' technique of refitting the Jeeps captured from his Brigade a few days earlier. They were both fitted out as I had been and were free to move about. Gerald's wound, however, kept him indoors. Tony and I spent our days helping the Underground to sift and pass information of dumps, batteries, troop movements, etc., to 2 Army, and visiting the increasing number of airborne soldiers hiding in the district in farms and villages. It was all most exciting and interesting, and several times we were able to witness, at close quarters, fighter bomber attacks which were the direct result of information passed a few hours earlier. At the same time with the help of an SAS wireless link in the neighbourhood, we organized two supply drops of arms, explosives, etc., to re-equip our force for sabotage in aid of the expected 2 Army push over the Rhine.

I need not tell you that this 'push' never came, and when this became clear, we started to think seriously of a mass evacuation.

Up to now we had been able to send a few in¬dividuals over the Rhine by a devious route a long way to the west; but for our numbers, which now amounted to some 15 officers and 120 other ranks of mixed origin, this was quite impracticable. We therefore formed a plan for crossing the river in the neighbourhood of Ede. Of the four requirements, a safe concentration area, the means of concentrating our very scattered force, a gap in the river defences, and the support of the 2 Army, the first alone was straightforward, as the country just north of the river was well wooded. The concentration of our force was simplified by a stroke of good luck at the last minute. The first patrol to the selected point of crossing showed it to be very strongly defended, so we tried again further to the east. A personal recce in daylight followed by two night patrols found a gap of some 400 yards between two positions, with a wooded approach to within half a mile of the bank. Finally David Dobie volunteered to cross the river immediately, by the route previously mentioned, to explain our intentions and elicit the support of 2 Army. The plans were accordingly made at a series of conferences held in Gerald Lathbury's house, and co-ordinated by nightly telephone conversations between David Dobie and myself, using a subterranean telephone line connecting various power stations north of the Rhine to Nijmegen.

A combination of events now made our situation extremely precarious and hastened our plans for departure. Up to now, although the area had been thickly populated with Germans, mostly L of C troops, artillery and troops passing through, with the usual smattering of SS and Gestapo, we had had no real difficulty with them. In fact our closest brush was an occasion, when I was stopped on the road and ordered to assist in pushing a Boche officer's car out of the ditch. Now, however, a large number of Gestapo and Grunei Politzei descended on Ede, and we received information that a round up of all males of working age was to be made in a week's time, to acquire labour for a further defence line. This invariably entailed a house to house search, which we would not be able to withstand; added to this several neighbouring Resistance Groups had recently been broken up, and our own friends were severely shaken by the presence of these large numbers of secret police. At the same time a squadron of tanks parked opposite my house and the personnel billeted themselves in the area, four coming to my house, which only had four rooms. However they were decent enough chaps, utterly fed up, and seemed content to sleep upstairs when off duty, oblivious of the fact that important conferences were being held beneath them; and although we often met they were content with a 'good morning or evening' in doubtful Dutch. Once, meeting two in the doorway, they had the good manners to stand aside and assist me to enter with a friendly arm on my shoulder.

Things were black indeed when we received the good news that all civilians were to be evacuated from an area four miles north of the river, in two days time. This meant crowded roads and great confusion, and so offered us an ideal opportunity to concentrate our force and saved us the necessity of making a long and hazardous night advance.

The plan briefly was this:

D—2 All evaders in the area of Ede (approx. 80) were to move on foot and bicycle, in one's and two's with Dutch guides, by main roads in daylight, to the concentration area three miles north of crossing place. Food for the following day, one blanket per man and all arms and ammunition, were to be conveyed to the area by horse and cart, disguised as vegetables, etc.

D—1 The remaining 40 evaders who were hiding some distance to the north-east were to be moved after dark in four Dutch lorries to the concentration area. They were to be in uniform and armed, with orders to fight if the lorries were stopped. D-Day By 0100 hrs our force was to be on the river bank. At this time a burst of tracer would be fired over the exact crossing place as a guide. On reaching the point we were to signal with a red torch for the boats to come across. The entire Corps Artillery was laid on should it be required. We were all to be armed and prepared to fight our way to the bank.

D—2 went entirely according to plan with no more than a few tense moments, and by nightfall the first part of the concentration was complete. That night I had my final co-ordinating telephone call to Nijmegen, who agreed to no cancellation under any circumstances.

On D—1, before midday, Gerald and I set off on bicycles; Gerald, dressed in a black clerical suit, the only one in the town that fitted him, looked, in his own words, like a 'very seedy Don'. We accomplished the 12 mile journey without event, passing a great many uninquisitive Boche, each one of whom we expected to stop us. There followed an interminable wait in the concentration area until an hour after dark, when the four lorries drew up at the appointed place. They debussed amidst great confusion and noise, and occupied so much of the road that a Boche cycle patrol had to ring their bells repeatedly to force a passage through.

I still dream of the three mile approach to the river that followed. Our force consisted largely of RAMC orderlies, and contained ten Dutchmen, several American airmen and two Russians. Never trained to this kind of warfare, their morale was badly shaken by weeks of evasion, and I can best describe that approach as a very jittery herd of buffalo stampeding through a wood. We passed through the gap without trouble, and then had to move parallel to the river for some 800 yards, between the river and the defences which were sited 400 yards back on the edge of the woods. A patrol bumped into us and opened fire, causing some consternation among our now thoroughly demoralized ranks. It must be realized that the men had never seen their officers before. This clash of fire was followed by red Verey lights from all along the Boche line, and we expected, what we most feared, a heavy artillery concentration on the river bank. Nothing happened, however, and we hurried on, until the tracer came over according to plan. A slight but very trying delay followed owing to our mistaking the crossing place. But eventually a friendly American voice guided us to the boats and so across the river. We had crossed within two miles of our Dropping Zone almost exactly a month before.

Before we succumbed to exhaustion and reaction, a great deal of the American's whisky went down our throats. At Nijmegen the hospital had been taken over for us and David Dobie had produced a case of champagne. The next day we flew to England.

In 1991 he went on to rewrite and publish his memoirs in a private publication entitled "DUTCH COURAGE AND PEGASUS" this was later in 1999 incorporated into an upgraded publication by the Ooosterbeek "Airborne Museum Hartenstein" and entitled "ESCAPE ACROSS THE RHINE".

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Proudly powered by Weebly