- HOME

- SOLDIER RESEARCH

- WOLVERTONS AMATEUR MILITARY TRADITION

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE RIFLE VOLUNTEERS 1859-1908

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BATTALION 1908-1947

- The Bucks Battalion A Brief History

- REGIMENTAL MARCH

-

1ST BUCKS 1914-1919

>

- 1914-15 1/1ST BUCKS MOBILISATION

- 1915 1/1ST BUCKS PLOEGSTEERT

- 1915-16 1/1st BUCKS HEBUTERNE

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS SOMME JULY 1916

- 1916 1/1st BUCKS POZIERES WAR DIARY 17-25 JULY

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS SOMME AUGUST 1916

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS LE SARS TO CAPPY

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS THE GERMAN RETIREMENT

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS TOMBOIS FARM

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS THE HINDENBURG LINE

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS 3RD BATTLE OF YPRES

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES 16th AUGUST

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES WAR DIARY 15-17 JULY

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS 3RD BATTLE OF YPRES - VIMY

- 1917-18 1/1ST BUCKS ITALY

-

2ND BUCKS 1914-1918

>

- 1914-1916 2ND BUCKS FORMATION & TRAINING

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS ARRIVAL IN FRANCE

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS FROMELLES

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS REORGANISATION

- 1916-1917 2/1st BUCKS THE SOMME

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS THE GERMAN RETIREMENT

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS ST QUENTIN APRIL TO AUGUST 1917

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS ARRAS & CAMBRAI

- 1918 2/1st BUCKS ST QUENTIN TO DISBANDMENT

-

1ST BUCKS 1939-1945

>

- 1939-1940 1BUCKS MOBILISATION & NEWBURY

- 1940 1BUCKS FRANCE & BELGIUM

- 1940 1BUCKS HAZEBROUCK

- HAZEBROUCK BATTLEFIELD VISIT

- 1940-1942 1BUCKS

- 1943-1944 1BUCKS PREPARING FOR D DAY

- COMPOSITION & ROLE OF BEACH GROUP

- BROAD OUTLINE OF OPERATION OVERLORD

- 1944 1ST BUCKS NORMANDY D DAY

- 1944 1BUCKS 1944 NORMANDY TO BRUSSELS (LOC)

- Sword Beach Gallery

- 1945 1BUCKS 1945 FEBRUARY-JUNE T FORCE 1st (CDN) ARMY

- 1945 1BUCKS 1945 FEBRUARY-JUNE T FORCE 2ND BRITISH ARMY

- 1945 1BUCKS JUNE 1945 TO AUGUST 1946

- BUCKS BATTALION BADGES

- BUCKS BATTALION SHOULDER TITLES 1908-1946

- 1939-1945 BUCKS BATTALION DRESS >

- ROYAL BUCKS KINGS OWN MILITIA

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE'S LINE REGIMENTS

- ROYAL GREEN JACKETS

- OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1965

- OXF & BUCKS LI INSIGNIA >

- REGIMENTAL CUSTOMS & TRADITIONS >

- REGIMENTAL COLLECT AND PRAYER

- OXF & BUCKS LI REGIMENTAL MARCHES

- REGIMENTAL DRILL >

-

REGIMENTAL DRESS

>

- REGIMENTAL UNIFORM 1741-1896

- REGIMENTAL UNIFORM 1741-1914

- 1894 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1897 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1900 DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1931 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1939-1945 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1950 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1960 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS (TA)

- 1960 REGIMENTAL MESS DRESS

- 1963 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1958-1969 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- HEADDRESS >

- REGIMENTAL CREST

- BATTLE HONOURS

- REGIMENTAL COLOURS >

- BRIEF HISTORY

- REGIMENTAL CHAPEL, OXFORD >

-

THE GREAT WAR 1914-1918

>

- REGIMENTAL BATTLE HONOURS 1914-1919

- OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY INTRODUCTION

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY

- 1/4 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 2/4 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 1/1 BUCKS BATTALION 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 2/1 BUCKS BATTALION 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 5 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 6 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 7 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 8 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 1st GREEN JACKETS (43rd & 52nd) 1958-1965

- 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND) 1958-1965

- 1959 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1959 REGIMENTAL MARCH IN OXFORD

- 1959 DEMONSTRATION BATTALION

- 1960 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1961 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1961 THE LONGEST DAY

- 1962 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1963 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1963 CONVERSION TO “RIFLE” REGIMENT

- 1964 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1965 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1965 FORMATION OF ROYAL GREEN JACKETS

- REGULAR BATTALIONS 1741-1958

-

1st BATTALION (43rd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

-

43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1914

>

- 43rd REGIMENT 1741-1802

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1803-1805

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1806-1809

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1809-1810

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1810-1812

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1812-1814

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1814-1818

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1818-1854

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1854-1863

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1863-1865

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1865-1897

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1899-1902

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1902-1914

-

1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919

>

-

1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1920-1939

>

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1920

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1921

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1922

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1923

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1924

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1925

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1926

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1927

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1928

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1929

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1930

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1931

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1932

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1933

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1934

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1935

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1936

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1937

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1938

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1939

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945 >

-

1 OXF & BUCKS 1946-1958

>

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1946

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1947

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1948

- 1948 FREEDOM PARADES

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1949

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1950

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1951

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1952

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1953

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1954

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1955

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1956

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1957

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1958

-

43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1914

>

-

2nd BATTALION (52nd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

- 52nd LIGHT INFANTRY 1755-1881 >

- 2 OXF LI 1881-1907

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1908-1914

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919

>

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919-1939

>

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1920

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1921

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1922

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1923

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1924

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1925

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1926

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1927

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1928

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1929

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1930

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1931

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1932

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1933

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1934

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1935

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1936

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1937

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1938

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1939

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945

>

- 1939-1941

- 1941-1943 AIRBORNE INFANTRY

- 1944 PREPARATION FOR D DAY

- 1944 PEGASUS BRIDGE-COUP DE MAIN

- Pegasus Bridge Gallery

- Horsa Bridge Gallery

- COUP DE MAIN NOMINAL ROLL

- MAJOR HOWARDS ORDERS

- 1944 JUNE 6

- D DAY ORDERS

- 1944 JUNE 7-13 ESCOVILLE & HEROUVILETTE

- Escoville & Herouvillette Gallery

- 1944 JUNE 13-AUGUST 16 HOLDING THE BRIDGEHEAD

- 1944 AUGUST 17-31 "PADDLE" TO THE SEINE

- "Paddle To The Seine" Gallery

- 1944 SEPTEMBER ARNHEM

- OPERATION PEGASUS 1

- 1944/45 ARDENNES

- 1945 RHINE CROSSING

- OPERATION VARSITY - ORDERS

- OPERATION VARSITY BATTLEFIELD VISIT

- 1945 MARCH-JUNE

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI DRESS 1940-1945 >

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1946-1947 >

-

1st BATTALION (43rd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

- MILITIA BATTALIONS

- TERRITORIAL BATTALIONS

- WAR RAISED/SERVICE BATTALIONS 1914-18 & 1939-45

-

5th, 6th, 7th & 8th (SERVICE) 1914-1918

>

-

6th & 7th Bns OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945

>

- 6th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI 1940-1945 >

-

7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI 1940-1945

>

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1940-JULY 1942

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JULY 1942 – JUNE 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JULY 1943–OCTOBER 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI OCTOBER 1943–DECEMBER 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI DECEMBER 1943-JUNE 1944

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JANUARY 1944-JUNE 1944

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1944–JANUARY 1945

-

5th, 6th, 7th & 8th (SERVICE) 1914-1918

>

- "IN MY OWN WORDS"

- CREDITS

NOVEMBER 1915 - THE BATTLE OF CTESIPHON.

EXTRACTED FROM THE REGIMENTAL CHRONICLES OF THE OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY

EXTRACTED FROM THE REGIMENTAL CHRONICLES OF THE OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY

BATTLE OF CTESIPHON.

(with the machine-guns.)

November 22nd.—Fell in at 6 a.m., and marched at 6.20. Heavy guns opened at 7, before sunrise. A gorgeous orange sky.

8.30 a.m.—We have halted, and I have the mules in a nullah, under cover, just in rear of S Company (Forrest's). Ctesiphon Arch is 2.500 yards by the range-finders—a wonderful ruin of tremendous size. There has been no sign or sight of the enemy, and, according to map, we ought to be already in their first-line trenches. The map must be wrong.

9 a.m.—The guns have ceased fire. We are going to advance in two lines of half-companies in fours. Machine-gun Section to follow in rear of S Company. Q and P Companies in first line; S and R in second line; 100 yards interval, and 450 yards distance.

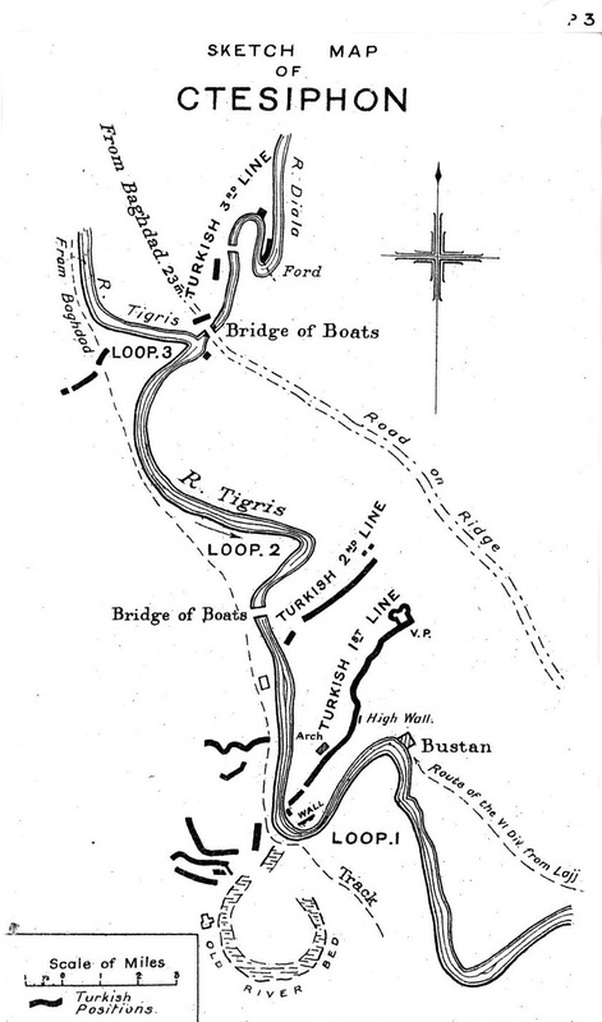

Sketch Map No. 3,

Here the Diary breaks off. Subsequently Lieut. Birch-Reynardson continued it:--

We advanced, for about 1,000 yards, over ground intersected by small nullahs some two or three feet deep. At, I should think, about 9.45 a.m. the enemy made his first sign by firing two groups of three shots each from a machine-gun on our left flank. This appeared to be the curtain-raiser, and soon afterwards shells began to arrive.

The 17th Brigade was quickly deployed, and luckily found some cover in a long ditch running parallel to the enemy's trenches, which were only about 400 yards in front of the Arch, instead of over a mile (according to the aeroplane map). From the ditches in which we were the range to the Arch was 1,200 yards.

Just to the left (S.W.) of the Arch we could see the entanglements in front of a redoubt, and thence a trench appeared to run to some high mounds or banks. Here were two machine-guns, and on the top of the mounds was a tin-roofed blockhouse or observation post.

We remained in this position for about an hour, or perhaps less, replying to the enemy's fire, from which we suffered very few casualties, though his shrapnel fire soon increased in volume and, by degrees, in accuracy. I heard afterwards that our guns could see nothing at this stage, because of a hopeless mirage.

The Brigade now got sudden orders to advance at right angles to its existing position, towards the work on the left of the enemy's position—the "vital point"—in front of which the force detailed for its capture was hung up and in urgent need of reinforcement.

This meant a march right across the enemy's front, at a distance of not more than 1,000 yards. It was an opportunity for the Turks, and they took it. Every available gun, machine-gun, and rifle was turned on to th0 ground over which the 17th Brigade marched. It was absolutely open and devoid of cover, and, consequently, the losses were very heavy indeed. But the steadiness of the advance was wonderful. The 22nd Punjabis and the 119th Infantry were particularly noticeable in the way in which they went ahead, as if nothing out of the common was happening—and it was trying work, as it was not a case of an exciting charge, but just a march across an open, bullet-swept plain.

Some 200 yards from the enemy's trenches south of V.P. (the "vital point") was a shallow ditch or irrigation channel, and this was reached by the survivors of the Brigade at about 12.30 p.m.

I came across Courtis, very badly wounded, and he asked me to take a message to the Colonel; so, leaving Sergeant Badby in charge of my Machine-gun Section, I went up to the firing line, and was hit almost at once. After this I knew very little of what was happening on the actual battlefield.

The Turks commenced "to flood our ditch, and the wounded had a thin time of it, trying to keep their heads below the low bank and their mouths above water. Those who were badly wounded would have drowned had they not been held up. Nearly everyone who showed his head over the edge of the bank here was hit by a sniper, and soon there were very few unwounded men in this part. Those who could still use their rifles had little ammunition left, so things did not look too bright.

Luckily the enemy was not giving us any shrapnel, otherwise we should have had a bad time, as the ditch was wide, and only some 2 ½ feet deep. A howitzer was dropping heavy H.E. shells fifty yards beyond us, making the ground shake, and sending up great columns of dark green smoke; but we were again fortunate, in that the wind was the other way. How long we lay here I do not know, but some time in the afternoon the " vital point " and the redoubts opposite to us were captured, and we could at last be taken from the water, which was icy cold and by now red with blood.

About sixty of us were laid out on the edge of the ditch, and our first field-dressings were put on. One good Samaritan chopped up an emergency ration and boiled some cocoa, which was very welcome to us after lying in the cold water. We were all shivering and shaking as if we had the ague, and for the first time blessed the warm sun of Mesopotamia. In the distance passed some Turkish prisoners, who willingly parted with some coats for us, and stretcher-bearers brought more coats and a few blankets from the captured trenches.

Night came on, and it became very cold. Some time after dark stretchers were brought, and we were carried to a spot near a dressing-station, and there put into a deep trench. I can remember being lifted out and taken to the dressing-station to have my wound dressed—an unpleasant experience—and then being replaced in the trench. Later, the Padre (Spooner) came along, but after that I can remember little until well on in the next day (November 23rd). It must have been about midday, as the sun was right over the trench, when someone, I think the Padre, gave me some brandy and tinned milk. The next I remember was early in same evening, when the battle seemed to be coming nearer again.

I heard a voice above the trench give orders for all wounded who could walk to get back. Carts, the voice said, were coming for us non-starters. The sounds of strife now began to get unpleasantly near, shrapnel burst close to our trench, and bullets came bouncing in. Suddenly there was a sound of galloping horses, and we heard shouts of Dushman ata ("the enemy is coming"). The shouts came from a few sowars—lost sheep without a shepherd—galloping back with the funks on board. Unfortunately, the transport carts for us had just arrived, and these the fugitive sowars successfully panicked. There were sounds of jolting and bumping, and the creaking of wheels, which gradually faded away in the distance. Then a voice said, "And what about these in the trench, sir ?;' And the reply came, " Oh, we can't move them now that those carts have gone ; they'll have to stay."

So we, six of us, in the trench stayed, and a doctor and the Padre with us. I remember I was quite awake now. There was a tremendous rifle-fire from in front, and bullets were whizzing over the trench and thudding into the parapet—evidently a determined counter-attack going on. The Padre was busy making a white flag, in case it should be wanted, for there was nothing else for it, as we were all helpless cases. When he had finished that, he came and spoke to each of us, and then proceeded to stand on the parapet under heavy fire, and give us the news, just as if he were on the stand of a race meeting, and we down in the crowd below. The last piece of news which I remember was : "They're 300 yards away, but it's: all right—we're giving them hell!"

They got no farther. By now it was almost dark—the sky deep blue, and the stars looking very large and yellow. Suddenly, against the blue of the sky, appeared a shadow. It seemed to hang on the edge of the trench for ages, and then rolled down almost on the top Of me, and became a Turk. I was not at all sure what he meant to do next, but as he came towards me I asked him what he wanted. He said that he was wounded and wanted water. I told him that I had none, but that he had better stay in the trench. However, he thought not, and disappeared again into the night. I hope he got his drink.

The rest of the night is but a dim recollection of star-shells and the crash of a battery firing close by, with an almost constant rattle of musketry.

When we awoke in the morning (24th November) everything was still, and we were told that we were to be moved. Soon, just as the sun rose, at about 7.15, the first carts arrived, and we were put into them. But we had to wait what seemed an interminable age until other carts were collected from the next Field Ambulance, so that we could all be formed up together. A few spent bullets moaned plaintively through the air as we waited. The only transport available consisted of A.T. carts, which have no springs, and are nothing more than iron frames on wheels, drawn by two ponies or mules. I was on a stretcher at the bottom of a cart, and two soldiers, one with a head wound and the other with a shattered ankle, were squeezed in beside me, hanging on as best they could. At last we got off. The desert surface here was like a ploughed field, and as hard as concrete. Over this we crashed and bumped for four hours in our springless carts; every few hundred yards a ditch had to be crossed, when the iron bottom of the cart seemed to rise up and hit one a smashing blow in the back; and, in addition, the ponies every now and then broke into a bucketing trot.

The Padre led us, and if it had not been for him we should have been much longer reaching Lajj, where the ships were. All through the last three days he had been with us, looking after us, feeding us, and reassuring us, with his cheeriness and coolness, when things looked bad, and showing absolute disregard for his own safety all along; his was a splendid example. I am glad to say that he was afterwards awarded the Military Cross.

At last, in the afternoon, we arrived at Lajj, and were embarked on the "Blosse Lynch" for down-river. We thought that we should be at Basra anyhow in a week, and we felt better for the thought. Lucky is it sometimes that we cannot foreknow the future !

The boat was crammed with wounded, and we lay like sardines up on the deck from stem to stern; there were some straw mattresses, but not enough to go round, and the deck was mightily hard for those without them. On the morning of the 25th we moved into the stream, two barges (also full of wounded) were lashed alongside, and then we made a start. That afternoon, when near Aziziyeh, we had to stop, as some paddle-blades were broken by a choppy cross sea, and we lay to all night. It rained hard, and soon water was pouring through the single awning, swamping the deck on which we lay, and wetting all the blankets. This was most unfortunate, as there was no possibility of drying them until next day, and there were no spare ones. On the afternoon of the 26th we arrived at Kut and that night were transferred to the "P. 2," as the "Blosse Lynch," being a shallow-draught boat, was wanted up-stream again. On the "P. 2" there were more stretchers, and the worst cases could now be put on these, which was a very great change for the better after the hard deck.

We began now to learn something of our casualties, which had been heavy. Most of the Indian regiments had only two or three British officers left. The three British regiments had lost about two-thirds of their numbers. Of the officers with the 43rd, Hyde, Forrest, Davenport, Courtis, Wynter, Kearsley, and Hind were killed, while Foljambe, Murphy, Webber, Hazell, Wilson, and myself were wounded. Of other ranks barely 160 were left on the morning of the 23rd November out of about 600.

Early on the 27th we started off down river, but in the afternoon, when just short of Sheikh Saad, two friendly Arabs came off in a canoe, and warned us to proceed no farther, as there was a large force of Arabs waiting for us round the corner. These we soon saw, and as we were without any form of protection or escort, it was thought advisable to turn back; so back we plugged to Kut, and arrived there next day, the 28th.

On the morning of the 29th we started again, this time as part of a big convoy of ships, preceded by H.M.S. "Butterfly," a new monitor, and also provided with a small escort of Indian troops. It was thought that we should get through without trouble, but, in case of accidents, our kit-bags, valises, etc., were piled up on the port side, to serve as a protection to the stretcher cases; walking cases were to go down into the iron barges on either side.

Our luck was clean out. Just before we reached the dangerous bend a shimal sprang up, and blew the monitor on to the bank. All the ships behind were held up, and soon we were all aground. This happened at about 12 noon, and at 1 p.m. the Arabs came. They opened fire at a range of some 900 yards, and until 5 p.m. we were sniped without intermission. The escort landed and went out to keep the Arabs back, but there was none too much ammunition, and the monitor was too close into the bank to use her 4-inch gun, though her 6-pounder and a machine-gun were able to keep down the enemy's fire. On our ship we had one man killed and five wounded, and I do not know how the other ships fared. It was not very pleasant lying behind our parapet of kit-bags (probably not bullet-proof) wondering what would happen next, and what we should do if the Arabs got on board—for we were close up against the bank. At last, just before dark, the monitor got off, and dispersed the Arabs with her 4-inch gun; but they could be seen collecting again a little farther down. The channel in front of us was difficult, and it was evident that we could not stay where we were. With feelings almost of despair we heard that we were to return again to Kut.

We arrived there on the morning of the 30th November, and did not make a fresh start until the 2nd December. In the meanwhile half a battalion of infantry and a section of mountain guns had been sent down to deal with the Arabs; and this time we got through safely, although we stuck on the mud just below Sheikh Saad, and had to stop for the night. It seemed as if our journey would never end.

There were only two doctors, an assistant surgeon, a British orderly, and four native sweepers to deal with all the cases on the ship and two barges. How many cases there were I do not know, but I do know that, although the doctors worked all day and most of the night, never seeming to eat and hardly ever to sleep, the worst cases could, as a rule, be dressed only every other day.

The doctors were perfectly wonderful, contending with every difficulty, working continuously on a crowded deck, without any of the conveniences of a hospital ship, and doing everything possible for our comfort. Fortunately we had been able to buy at Kut chickens, eggs, and some vegetables, on which we depended to help out the ration bully-beef—now quite uneatable to many. Bread ran short before we reached Amara, and those who could manage to do so ate biscuit.

On the afternoon of the 3rd we ran hard aground below Ali-al-Gharbi, and stuck there until next morning, when we succeeded in getting off, and arrived at Amara that night. Here all the slighter cases were to have been evacuated, but the hospital accommodation was found to be hopelessly inadequate, and only those in need of an immediate operation were removed.

We started again on the afternoon of the 5th, and, though losing a lot of time continually running aground, we managed to get off every time, and by the morning of the 6th we were just above Kurna, with the prospect of reaching Basra that night. But our engines now had an accident, and, after the necessary repairs had been effected, we could proceed only at half speed, and it was 4 p.m. on the 7th when at long last we got to Basra.

After some delay we were transferred to barges, but these did not leave the ship until 7 p.m., and then, owing to a mistake on someone's part, our barge was towed to the bank near the hospital, where, for a space of some two hours, Arab coolies proceeded, across our prostrate and very weary forms, to unload medical stores from the barge.

But in the end came paradise ! At 10 p.m. we were alongside the hospital ship "Varela," and by 10.30 we found ourselves in brightly-lit and clean wards, with swing cots, white sheets, electric fans, and gentle nurses. We knew that at last all was well, and that we were awake in heaven, after fifteen days of the very worst nightmare.

Next morning by 6 a.m. we had up-anchored, and by 11 were at the mouth of the river, heading our course for India. Mesopotamia dropped below the skyline and became a thing of the past, and we were not sorry to say good-bye. We had sampled all its seasons and five hundred miles of its marshes and plains. Most of us agreed with somebody's remark : "Well, it was five hundred miles too much."

Company-Sergeant-Major Shilcock gives the following description of the Battle of Ctesiphon, in which he took part:--

We left bivouac before daylight, and just after dawn commenced digging. Whilst we were digging our trenches our 5-inch and 4-inch batteries and a monitor on the river were bombarding the enemy's position; but, as no reply came, we concluded that he had retired on Baghdad. Soon, however, we heard heavy rifie and artillery fire a long way to our right, which told us that our other brigades were in action, and through our glasses we could see parties of Turks moving about in their positions.

When the G.O.C. 17th Brigade came up he gave orders to the effect that, instead of remaining where we were, we were to go up to assist the others. The 43rd advanced in two lines, P and Q in the front line, and R and S in support. When we had advanced a short distance towards the great Ruin, we were ordered to change direction and move along the enemy's front, the objective being a large redoubt.

All grass in front of the position had been burnt, except a patch here and there, which was used by the enemy as a range mark; posts also had been set up for the same purpose. When we were advancing over this burnt ground our khaki uniforms showed up very plainly, and, when near any of the above mentioned marks, our casualties were heavy.

The fighting was very severe, but eventually we turned the enemy out and captured his position.

During the action we took 11 guns, 8 in one place and 3 in another. These guns were taken and retaken by us three times, and finally, having no horses to remove them, they were abandoned, after we had destroyed the breech of each;

The Turks retired, leaving a large number of prisoners in our hands, but in the afternoon, having been reinforced from Baghdad by about 2 ½ Divisions, they attacked about 4 p.m., and tried to drive us out. They did not succeed in doing so, and they lost very heavily, reports stating that they had about 5,000 casualties.

At Roll-call that evening 137 of the 43rd answered their names. About 600 went into action. All our wounded were got to the river on the 24th, when General Townshend retired, and, after very heavy fighting, arrived at Kut-el-Amara on the 3rd December.

C.-S.-M. Shilcock was wounded at Ctesiphon aud invalided to England. He did not, therefore, take part in the retirement to Kut.

The following notes on the British force and on the Turkish position at Ctesiphon were put together afterwards by Captain Birch-Reynardson :--

At the time of the advance on Ctesiphon there were in Mesopotamia still only the two Divisions, viz. : the 6th and the 12th, and it is interesting to note that the 12th Division (less the 30th Infantry Brigade, which was with the 6th Division) was guarding the lines of communication and the whole country in rear of us, having detachments at Ahwaz (Persia) on the right, at Basra in the centre to Nasiriyeh (Euphrates) on the left, and up-stream (Tigris) at Kurna, Kalaat Salih, Amara, Ali-al-Gharbi, Sannaiyat, Kut, and Aziziyeh. It is also noteworthy that the artillery of the 12th Division consisted of no more than the 23rd and 30th Mountain Batteries and an Indian Volunteer Battery of old 15-pounders. Now the distance from Basra to Ahwaz, by the Karun River, is 150 miles; to Nasiriyeh, by the Shatt-el-Arab and Euphrates, 135 miles; and to Aziziyeh, by the Tigris, 400 miles.

The 6th Division consisted of the same units as had fought at Es Sinn, their casualties having been made good by drafts. The 30th Brigade (12th Division) was now up to strength ; "S" Battery, R.H.A., had joined the Cavalry Brigade, while the Naval Flotilla had been increased by the new monitor "Firefly," put together at Abadan, and carrying a 4-inch, a 6-pounder, and a machine-gun. This was the force which advanced on Ctesiphon.

As regards the Turks opposed to us: We knew for certain that they numbered 7,000, with about 40 guns, including, report said, three batteries of Krupp Q.F. and some heavy guns; but before the battle, probably by November 18th, unknown to us, they had been very heavily reinforced, and were able to meet our attack with probably as many as four Divisions, if not even six. Their position at Ctesiphon was, as at Es Sinn, astride the river, and though resembling it in some ways, it was decidedly stronger and had been prepared for a long time. It was also a fairly good natural position, and, unlike the Es Sinn lines, did not depend on the vagaries of temporary floods for the protection of its flanks. But in rear of it flowed the Diala River, provided with only two bridges, and in this fact seemed to lie our chance of a haul.

Briefly, the position may be described as follows: The Tigris hereabouts flows approximately north and south, but having, as the map shows, three considerable loops, which played an important part in the Turkish plans. The first loop is a bend to the southwest two miles deep, and within it, on the left bank, stands the great ruin of Ctesiphon Arch, with the enemy's first line just in front of it. The second bend runs north-east, and then curls, by the west, to north at the third bend, where there is an almost hair pin bend due east. At this last bend is the confluence of the Tigris and the Diala. Between the first and the third bend the distance is twelve miles as the crow flies, and twenty-five by the river's course.

On the left bank the enemy's first line extended from the bottom of loop 1 for about six miles in a north-easterly direction, and consisted of trenches with redoubts at close intervals, the left flank resting on high ground, whereon was erected a large and strongly-fortified redoubt—the Vital Point.

On this (left) bank were some 22 gun-emplacements, of which 12 were round about the large redoubt on the left flank. Eight guns were about the centre of the position, and one was just south-west of the Arch, which itself stood a little in rear of and about three-fourths of the way down the line.

A mile in rear of the first line was the second line, its right resting on the river, and its left almost directly behind the large redoubt, while gun-emplacements had been prepared slightly in rear of the left flank of the second line. Half a mile farther in rear, at the beginning of loop 2, was a bridge across the river.

On the right bank the ground was tremendously broken and cracked, being, in fact, dry, sun-baked marsh, and was further cut up by mounds and old canals, running out into the desert towards the south. Here there appeared to be 14 guns, and great use had been made of the broken ground, every canal and mound having been put into a state of defence.

There was no regular line of redoubts, but the defences extended for about four miles towards the south, with the right flank bent back towards the west. As a matter of fact the enemy knew quite well that he had little to fear on this side of the river, as the ground was so cracked and fissured as to be impassable. The second line on this bank was more advanced, than on the left bank, and consisted of entrenchments on the slopes of long water-cuts, running westward into the desert for about four miles. There were also gun-emplacements, but these were probably alternative positions.

The enemy's next line was right away back on the far bank of the Diala River, which, as I have already mentioned, was bridged at two points—close to its junction with the Tigris, and a mile and a half farther up-stream. Each of these bridges was covered by trenches in rear, as was also a ford across the Diala two miles or so higher up; but it was doubtful if this ford was passable.

The line of retreat was evidently along the left bank of the Tigris and across the Diala by the two bridges and the ford, the enemy troops on the right bank probably being intended to cross to the left bank by the Tigris bridge, although there did exist a rough track all along the right bank to what appeared to be an entrenched high-level canal. The main caravan route ran along a ridge two miles or so beyond the left of the enemy's position, and crossed the Diala by the lower bridge, the distance from which to Baghdad is 23 miles.

The above description of the position is not, of course, from a personal view of the ground, but, from what could be made out before the battle, from the official maps which had been compiled from aircraft reports and photographs. The description may not be accurate, but it contains all that we knew of the position when we advanced to the attack.

With regard to the plan of operations : As at Es Sinn, our force was divided into three columns; the main attack to be pushed in against the large redoubt (Vital Point), on the enemy's left flank by the 16th Brigade and two battalions of the 30th Brigade; the 18th Brigade, on their right, was to make a turning attack ; and on the extreme left the 17th Brigade was to deliver a holding attack against the enemy's right (on the left bank), opposite the' Arch; while the Cavalry Brigade, with a battalion of the 30th Brigade in carts, was to make a wide turning movement round and behind the left of the position, with the object of cutting off the enemy's retreat across the Diala. The right bank was to be left alone This is a brief outline of the scheme; but, owing to the fortunes of war, by which I was prevented from seeing much of the fight my account of it is perforce rather vague.

There is one matter to which I have not referred the Arch as an enemy observation post. How far or how much the Turks could see from its top I cannot say, but it must have been invaluable to them for observing our approach and dispositions on the morning of the attack. Bets were made as to whether our heavy batteries would knock it endways, but they refrained, and the Ctesiphon Ruins still stand, though, perhaps, we paid a somewhat high price for their preservation.

"An officer of the Regiment present at the battle, on the Staff, writes: "The main attack got in, but, instead of swinging round to clear the enemy trenches facing the 17th Brigade, they went on in pursuit of the fugitive Turks and thus came up against the enemy second line. The 17th Brigade were unable to get through unaided, so were brought round to the Vital Point and taken on to reinforce the 16th and 30th Brigades. But their losses had been already so heavy that the numbers the Brigade could bring into the fight were less than the strength of a battalion.. ,,

Proudly powered by Weebly