- HOME

- SOLDIER RESEARCH

- WOLVERTONS AMATEUR MILITARY TRADITION

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE RIFLE VOLUNTEERS 1859-1908

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BATTALION 1908-1947

- The Bucks Battalion A Brief History

- REGIMENTAL MARCH

-

1ST BUCKS 1914-1919

>

- 1914-15 1/1ST BUCKS MOBILISATION

- 1915 1/1ST BUCKS PLOEGSTEERT

- 1915-16 1/1st BUCKS HEBUTERNE

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS SOMME JULY 1916

- 1916 1/1st BUCKS POZIERES WAR DIARY 17-25 JULY

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS SOMME AUGUST 1916

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS LE SARS TO CAPPY

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS THE GERMAN RETIREMENT

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS TOMBOIS FARM

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS THE HINDENBURG LINE

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS 3RD BATTLE OF YPRES

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES 16th AUGUST

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES WAR DIARY 15-17 JULY

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS 3RD BATTLE OF YPRES - VIMY

- 1917-18 1/1ST BUCKS ITALY

-

2ND BUCKS 1914-1918

>

- 1914-1916 2ND BUCKS FORMATION & TRAINING

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS ARRIVAL IN FRANCE

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS FROMELLES

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS REORGANISATION

- 1916-1917 2/1st BUCKS THE SOMME

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS THE GERMAN RETIREMENT

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS ST QUENTIN APRIL TO AUGUST 1917

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS ARRAS & CAMBRAI

- 1918 2/1st BUCKS ST QUENTIN TO DISBANDMENT

-

1ST BUCKS 1939-1945

>

- 1939-1940 1BUCKS MOBILISATION & NEWBURY

- 1940 1BUCKS FRANCE & BELGIUM

- 1940 1BUCKS HAZEBROUCK

- HAZEBROUCK BATTLEFIELD VISIT

- 1940-1942 1BUCKS

- 1943-1944 1BUCKS PREPARING FOR D DAY

- COMPOSITION & ROLE OF BEACH GROUP

- BROAD OUTLINE OF OPERATION OVERLORD

- 1944 1ST BUCKS NORMANDY D DAY

- 1944 1BUCKS 1944 NORMANDY TO BRUSSELS (LOC)

- Sword Beach Gallery

- 1945 1BUCKS 1945 FEBRUARY-JUNE T FORCE 1st (CDN) ARMY

- 1945 1BUCKS 1945 FEBRUARY-JUNE T FORCE 2ND BRITISH ARMY

- 1945 1BUCKS JUNE 1945 TO AUGUST 1946

- BUCKS BATTALION BADGES

- BUCKS BATTALION SHOULDER TITLES 1908-1946

- 1939-1945 BUCKS BATTALION DRESS >

- ROYAL BUCKS KINGS OWN MILITIA

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE'S LINE REGIMENTS

- ROYAL GREEN JACKETS

- OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1965

- OXF & BUCKS LI INSIGNIA >

- REGIMENTAL CUSTOMS & TRADITIONS >

- REGIMENTAL COLLECT AND PRAYER

- OXF & BUCKS LI REGIMENTAL MARCHES

- REGIMENTAL DRILL >

-

REGIMENTAL DRESS

>

- REGIMENTAL UNIFORM 1741-1896

- REGIMENTAL UNIFORM 1741-1914

- 1894 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1897 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1900 DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1931 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1939-1945 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1950 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1960 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS (TA)

- 1960 REGIMENTAL MESS DRESS

- 1963 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1958-1969 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- HEADDRESS >

- REGIMENTAL CREST

- BATTLE HONOURS

- REGIMENTAL COLOURS >

- BRIEF HISTORY

- REGIMENTAL CHAPEL, OXFORD >

-

THE GREAT WAR 1914-1918

>

- REGIMENTAL BATTLE HONOURS 1914-1919

- OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY INTRODUCTION

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY

- 1/4 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 2/4 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 1/1 BUCKS BATTALION 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 2/1 BUCKS BATTALION 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 5 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 6 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 7 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 8 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 1st GREEN JACKETS (43rd & 52nd) 1958-1965

- 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND) 1958-1965

- 1959 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1959 REGIMENTAL MARCH IN OXFORD

- 1959 DEMONSTRATION BATTALION

- 1960 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1961 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1961 THE LONGEST DAY

- 1962 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1963 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1963 CONVERSION TO “RIFLE” REGIMENT

- 1964 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1965 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1965 FORMATION OF ROYAL GREEN JACKETS

- REGULAR BATTALIONS 1741-1958

-

1st BATTALION (43rd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

-

43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1914

>

- 43rd REGIMENT 1741-1802

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1803-1805

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1806-1809

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1809-1810

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1810-1812

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1812-1814

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1814-1818

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1818-1854

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1854-1863

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1863-1865

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1865-1897

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1899-1902

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1902-1914

-

1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919

>

-

1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1920-1939

>

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1920

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1921

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1922

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1923

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1924

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1925

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1926

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1927

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1928

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1929

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1930

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1931

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1932

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1933

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1934

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1935

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1936

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1937

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1938

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1939

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945 >

-

1 OXF & BUCKS 1946-1958

>

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1946

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1947

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1948

- 1948 FREEDOM PARADES

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1949

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1950

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1951

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1952

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1953

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1954

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1955

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1956

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1957

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1958

-

43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1914

>

-

2nd BATTALION (52nd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

- 52nd LIGHT INFANTRY 1755-1881 >

- 2 OXF LI 1881-1907

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1908-1914

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919

>

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919-1939

>

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1920

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1921

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1922

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1923

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1924

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1925

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1926

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1927

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1928

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1929

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1930

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1931

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1932

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1933

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1934

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1935

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1936

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1937

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1938

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1939

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945

>

- 1939-1941

- 1941-1943 AIRBORNE INFANTRY

- 1944 PREPARATION FOR D DAY

- 1944 PEGASUS BRIDGE-COUP DE MAIN

- Pegasus Bridge Gallery

- Horsa Bridge Gallery

- COUP DE MAIN NOMINAL ROLL

- MAJOR HOWARDS ORDERS

- 1944 JUNE 6

- D DAY ORDERS

- 1944 JUNE 7-13 ESCOVILLE & HEROUVILETTE

- Escoville & Herouvillette Gallery

- 1944 JUNE 13-AUGUST 16 HOLDING THE BRIDGEHEAD

- 1944 AUGUST 17-31 "PADDLE" TO THE SEINE

- "Paddle To The Seine" Gallery

- 1944 SEPTEMBER ARNHEM

- OPERATION PEGASUS 1

- 1944/45 ARDENNES

- 1945 RHINE CROSSING

- OPERATION VARSITY - ORDERS

- OPERATION VARSITY BATTLEFIELD VISIT

- 1945 MARCH-JUNE

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI DRESS 1940-1945 >

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1946-1947 >

-

1st BATTALION (43rd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

- MILITIA BATTALIONS

- TERRITORIAL BATTALIONS

- WAR RAISED/SERVICE BATTALIONS 1914-18 & 1939-45

-

5th, 6th, 7th & 8th (SERVICE) 1914-1918

>

-

6th & 7th Bns OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945

>

- 6th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI 1940-1945 >

-

7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI 1940-1945

>

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1940-JULY 1942

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JULY 1942 – JUNE 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JULY 1943–OCTOBER 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI OCTOBER 1943–DECEMBER 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI DECEMBER 1943-JUNE 1944

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JANUARY 1944-JUNE 1944

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1944–JANUARY 1945

-

5th, 6th, 7th & 8th (SERVICE) 1914-1918

>

- "IN MY OWN WORDS"

- CREDITS

THE REGIMENT ON D DAY JUNE 6th 1944

BASED ON EXTRACTS FROM THE REGIMENTAL WAR CHRONICLES OF THE OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY VOL4 1944-1945

PREPARATION FOR INVASION

The tasks of the 6th Airborne Division were:

1. To seize intact the bridges over the Canal de Caen and the River Orne at Benouville and Ranville and to secure a bridgehead of sufficient depth to ensure that these could be held.

2. To seize and silence an important coastal battery at Merville before seaborne assault took place.

3. To destroy the bridges over the River Dives at Varaville, Robehomme Bures and Troarn.

4. To delay, and interfere with as much as possible, the movement of any enemy reinforcements from the east towards Caen.

5. To seize the seaside towns of Sallenelles and Franceville Plage. (This was the role of the 1st Special Service Commando Brigade under command.)

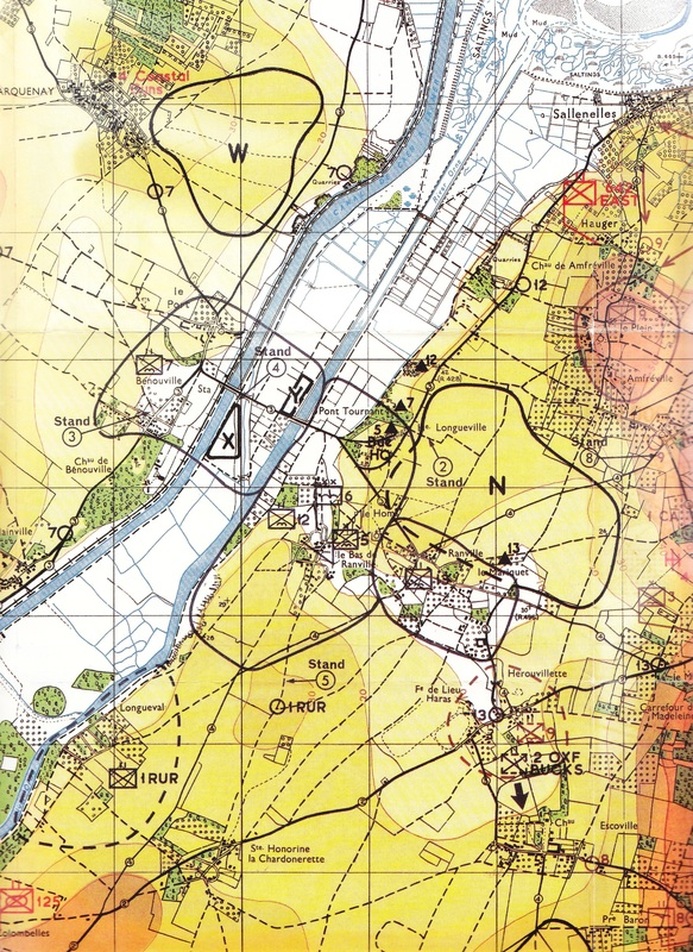

The 6th Airlanding Brigade, together with the 5th Parachute Brigade, was concerned with the first and fourth tasks given above, whilst the 3rd Parachute Brigade’s role covered the second, third and also the fourth. Map 3 gives the dropping zones and landing zones.

The role of the 6th Airlanding Brigade, which consisted of the 52nd, 1st Battalion The Royal Ulster Rifles and the 12th Battalion The Devonshire Regiment, was to occupy the southern flank of the divisional perimeter. The Royal Ulster Rifles were to seize Ste Honorine and the 52nd Escoivile. The 12th Devons were to occupy a feature in the centre known as Ring Contour 72. These positions were to be secured by the day after D Day. In addition, the 52nd was given the most important task of providing a coup-de-main force of six platoons whose fortunes have already been described.

The division was to be carried to Normandy in two lifts. The parachute brigades and the 52nd coup-de-main force were to leave on the night before D Day, followed by divisional headquarters and divisional troops. The 52nd, together with the Royal Ulsters, were in the second flight, due to leave Engiand on the afternoon of D Day. The other battalion of the airlanding brigade, the 12th Devons, had to join the seaborne invasion owing to shortage of aircraft.

Excellent briefing facilities were available, in the first instance, for company commanders in the secret briefing rooms, and, secondly, for all members of the Regiment at a later stage when on the airfields. The country over which we were to operate could be studied in minute detail with the aid of beautifully constructed cloth models which showed detail down to hedgerows and individual buildings. Air photographs taken up to the last moment enabled us to plan down to the very location of section posts in Escoville should we arrive there as planned.

Situation maps gave the latest information of enemy localities, defences and troop movements. A guide book gave a wealth of local information. We were therefore able to study the ground and our opponent’s moves, trace the defences of the 711th and 716th German Infantry Divsions in our battle area, watch the movements of the German counter-attack divisions, and, for instance, note and wonder at the sudden move of the 21st Panzer Division to the Caen area. Did the enemy know where we were to land? If not, why had the panzer division moved? And why were anti-glider landing poles being erected in the areas where our landing zones were planned?

Training continued up to the last available day. The intricate plans for each glider load were worked out, weapons, equipment, vehicles and kits checked and rechecked, and then, a few days before D Day. Bulford saw us no more and we moved to concentration areas on the airfields from which we were to fly into battle.

The last parade and the move to the airfields differed little from the parades we had held so many times before going on exercises. Perhaps a certain tension and finality in the tone of C.S.M. Belcher’s voice, as he reported Letter C Company present, echoed all our feelings that at long last we were really off to face our unknown destinies.

The 52nd moved to sealed camps at Tarrant Rushton, Harwell and Keevil

airfields. Those of us at Harwell thought it a good omen that we were to depart from Oxfordshire.

However, the particular stubble field, surrounded by a barbed-wire fence, across the road from the airfield was not one of the county’s choicer spots. In this camp we were completely sealed from the outside world, no contact whatsoever being allowed with anyone not in the Regiment, and no one being allowed beyond the barbed-wire perimeter, except the loading parties, which were closely shepherded to the glider parking area on the airfield.

The time spent in the concentration camps was not wasted. Intensive briefing was done with the aid of the models and photographs that had been set up in the huts in the camp. Every soldier was put in the picture fully and shown the ground over which he would fight. Particular study was made of the village of Escoville and its approaches, for this was our ultimate objective. The ground in the area of our landing zone was also care-fully scrutinized so that landmarks could be picked up if gliders went astray. The intense desire by all ranks for knowledge of the operation and of the area of operations was perhaps natural, but it was a comfort to see such enthusiasm.

Whilst in the concentration area we were issued with our escape kits which

included silk maps, compasses, hard rations, hacksaw blades, money, magnetic buttons and even fishing hooks. Men of the Regiment vied with each other in ingenuity for concealment of the items in their clothing. One soldier remarked that he had never had magnetic fly buttons before and wondered what effect they might have. Company commanders had to sign for large amounts of liberation francs, to be used only in an emergency, and we wondered if an equivalent amount would be added to our overdrafts if they were lost or improperly used.

Two days before D Day equipment and vehicles were loaded into our gliders. The lashings were checked and checked again, for we were fully aware of the dangers of loose or runaway equipment in a glider.

All was now ready for the big event, but the weather had intervened and it was not till the 5th June, 1944, that we heard that we would go on the

morrow.

That evening a small party from Regimental headquarters visited Tarrant Rushton airfield to see the take-off of the coup de-main party commanded by Major R J. Howard. They were in excellent heart and looked very impressive with their blackened faces, airborne helmets and clothing already camouflaged. They were airborne at about 2130 hrs on the 5th June, and so began the 52nd’s part in the great assault of the 6th June, 1944. with the 52nd taking the honour by providing, in the coup-de-main force, the first fighting troops to land in Europe.

Meanwhile we at Harwell bade au revoir to the first glider lift. Included in this party was our small advanced party, led by Major M. M. Darell-Brown. He was, however unsuccessful in reaching Europe at his first attempt, as his giider made a forced landing in England and we were more than surprised to find him having an early breakfast the next morning. He was even less talkative than usual at such an hour.

The day of D Day (6th June, 1944) was spent in final checks and company commanders attended the R.A.F. briefing of tug aircraft and glider pilots, and listened to technical details for the flight, cast-off and landing. The cheerful approach by the R.A.F. to the operation was very encouraging and the meteorological officer got his usual laugh. We were then asked to give the pilots an outline of our company tasks, in which the pilots showed great interest. Every spare moment of the day was spent with ears glued to the wireless. The broadcasts in both French and English on that June morning will long be remembered by those who knew that before long they too would be joining in the “grand debarquement des Allies.”

It was with few regrets that, after tea on the 6th June, we left our camp and moved to the airfield. An impressive array of Horsa gliders lined up on the edge of the runway awaited us. A brief command and we split up into our glider parties and waited for the order to emplane. The impression I got was that the men were quiet, but confident and keen to get on with the job. Such laughter as there was seemed slightly forced and directed mainly at remarks, some rude, some humorous, chalked on the fuselages of the gliders. At about 1830 hrs. with final wishes of bon voyage over, we were in our gliders. In the glider we all wore Mae Wests and had a rapid rehearsal of our ditching drill in case we pranged (This is believed to be current slang in the R.A.F. for crashed or forced to land) in the English Channel. Then with safety belts adjusted we waited for the jerk as the tug took the strain on the tow rope. Soon it came and those in the front seats could see themselves hurtling down the smooth runway behind of the tug. Then we were airborne and once again we heard the familiar whistle as the air rushed by and we glided higher and higher into the evening sky. The first hour of flying was spent in moving to a rendezvous over the south coast of England and then in taking up position in the air armada which was quickly forming for France.

Once inside a Horsa glider, except for a person standing in the hatchway leading into the pilot’s cockpit, the view outside is restricted. Small portholes allow a limited vision to either side, but little can be seen except sky and an occasional glimpse of the nearer tugs and gliders. This soon becomes boring and it was interesting to note the reactions of one’s fellow-passengers. Most were soon asleep. This was the usual reaction on long practice flights and even the excitement of our present flight could not break the old hands of the remarkable aptitude of the British soldier for sleep. Others were reading newspapers and an occasional song was hummed. The only two persons looking in any way perturbed were two men of the Corps of Military Police who were flying with us. They were really parachutists, it was their first flight in a glider, and they obviously missed their parachutes. Glider troops carry no parachutes.

The air fleet eventually passed over the coast in the Portsmouth area and headed across the sea. For a short time we were out of sight of land and could only see silvery dots which were ships on the sea below. The sea appeared calm. Our fighter escort was by now weaving and turning above and around us. One could not help wondering whether all the planes sweeping to and fro were’friendly. A glider is very helpless if attacked in the air and, although we had been told to fire Brens through the glider’s portholes in the event of air attack, we were not too confident of ou prowess as air gunners. Events proved that all aircraft sighted were friendly.

Very soon the French coast came into sight. We had dropped altitude to about 3,000 feet and it was soon possible to see ahead of us the mass of shipping off the beaches. There seemed to be thousands of ships of every shape and size. Beyond the ships the yellow line of the beaches stretched out to our right and left, with the green and yellow fields of Normandy forming the background.

Haze and smoke prevented, at this stage, the identification of any landmarks, but once over the coastline it was possible to pick out the line of the River Orne and out ahead the town of Caen.

Our navigator had not failed us: we had arrived.

The thoughts of all those in a position to get a view of the ground below must have been the same. Where was our landing zone? Would the pilots find it? Would it be free of enemy? Would it be clear of the anti-glider landing poles?

Suddenly one of the glider pilots pointed below, and there was the landing zone. A moment later he made another motion with his hand as puffs of black smoke began to appear in the sky, followed by the cracking thuds so well known to war-time airmen. It was flak (German for anti-aircraft fire) the enemy was somewhere below us. Then came the moment for cast-off. I noticed the sweat breaking out on the necks of the glider pilots and with a muttered “Here we go we were clear of our tug and had begun our slow spiral descent to earth. The time was about 2130 hrs. Glancing back into the body of the glider, C Company headquarters staff were sitting stiffly in the seats. It must have been an ordeal for them, being unable to see what was happening. No one had been hit by flak and a quick “We’re O.K.” brought relief to the faces of those I could see.

Looking again over the glider pilot’s shoulder I could see the first gliders about to land. They seemed to be coming in from all angles and as we approached to land the language of the pilots became unprintable. The landing plan was obviously not working with the precision expected. In order to avoid a mid air collision our senior glider pilot made a split-second decision to land just off the actual landing zone. Leaning forward to place my arms in a protective position around my head, I felt the glider touch down and saw that we were making straight towards a large hedge. An almighty crash and splintering of wood followed, then silence and the glider had stopped.

Our landing drill worked and all-round defence around the glider was at once adopted. Our glider no longer had any wheels, wings or tail, otherwise it seemed undamaged, although we had ploughed a lane through a large hedge.

No one was the worse for the experience except for a few bruises. The jeeps and other equipment were being unloaded and the signaller was struggling to re-net the somewhat shaken wireless sets.

This landing was typical of many landings: some were better, some much worse. In fact, all the gliders of the Regiment, except four, landed in or near the landing zone, and in spite of the many crash landings and collisions that took place our casualties were small.

The position on the landing zone was rather obscure. Firing was going on in the area of Benouville, chosen as the Regimental rendezvous, and there was also a certain amount of firing on the landing zone itself. One glider ended up in an enemy slit trench, the occupants of which quickly surrendered, being quite unnerved by the sudden descent of a large number of gliders on their position.

The adjutant, doctor and serjeant-major were rather astonished to find a real live German about ten yards from them when they leapt from their glider. After a certain amount of fumbling for weapons they succeeded in taking their first prisoner.

After a certain amount of delay, during which time enemy were cleared out of Benouville by a battalion of the 3rd Infantry Division and ourselves, the

Regiment assembled as arranged just west of the River Orne and at 2215 hrs began to move to the prearranged concentration area east of the River Orne. Four of our gliders were still missing. These contained a platoon of Letter B Company, a detachment of the mortar platoon and the intelligence officer’s party. It was ‘learned later that they had landed in England and Lieutenant R. M. Osborne joined us the next day, having travelled by sea. Of the officers injured on the landing zone the assistant adjutant, Lieutenant L. Nicholson, had to be evacuated, but the commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel M. W. Roberts, was able to carry on for a time, although injured when his glider came into collision with another glider whilst still some ten feet from the ground.

The situation in the divisional bridgehead area when the 52nd landed was as follows: 7th Parachute Battalion was in position holding an area west of the River Orne bridges. The remainder of the 5th Parachute Brigade (12th and 13th Battalions) were holding the bridgehead to the south-east of the bridges in the Bas de Ranville—Ranville—Ranville le Mariquet area.

The 3rd Parachute Brigade, having destroyed the German coastal battery south of Merville and the bridges over the River Dives, was operating on an approximate line Hauger—Le Mesnil—Bois de Bavent.

The 1st Special Service Brigade was fighting its way towards Sallenelles. All battalions had had very heavy fighting during the day against heavy German pressure on the bridgehead. By 2300 hrs on the 6th June the 52nd was concentrated east of the River Orne. The move to the area was uneventful except that the night was dark and our move coincided with a supply drop in the area by the R.A.F.

Large hampers full of stores were falling to the ground close to our route and occasionally the parachutes failed to open and the threat from a “free drop” hamper seemed worse than the odd enemy shell. When passing over the Orne bridges we learnt first hand of the brilliant success of our coup-de-main party.

Major John Howard met the commanding officer on the bridges as we passed over. It was, however, sad to hear of the first 52nd casualties, particularly the death of Lieutenant Den Brotheridge, who was killed at the head of his platoon in its gallant assault on the western end of the bridge.

From the concentration area the Regiment was ordered forward at 0130 hrs to the area of the chateau at Ranville with orders to go forward to Herouvillette at first light. At Ranville companies took up all-round defence positions in the chateau grounds. The 13th Parachute Battalion was holding this area and had had a tough time since landing the previous evening. Lieutenant-Colonel P. J. Luard, their commanding officer, was, however, in good heart and told us that they had been in contact with the enemy till darkness had fallen. He thought that Herouvillette was held by the enemy.

During the early hours of the morning of the 7th June C Company sent a fighting patrol into Herouvillette but found the it deserted. At Ranville the coup-de-main force returned to the Regiment. Captain B. C. E. Priday and his glider party also turned up. 1

1. The Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry Chronicle, Vol 4: June 1944 - December 1945 Pages 71-81

BASED ON EXTRACTS FROM THE REGIMENTAL WAR CHRONICLES OF THE OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY VOL4 1944-1945

PREPARATION FOR INVASION

The tasks of the 6th Airborne Division were:

1. To seize intact the bridges over the Canal de Caen and the River Orne at Benouville and Ranville and to secure a bridgehead of sufficient depth to ensure that these could be held.

2. To seize and silence an important coastal battery at Merville before seaborne assault took place.

3. To destroy the bridges over the River Dives at Varaville, Robehomme Bures and Troarn.

4. To delay, and interfere with as much as possible, the movement of any enemy reinforcements from the east towards Caen.

5. To seize the seaside towns of Sallenelles and Franceville Plage. (This was the role of the 1st Special Service Commando Brigade under command.)

The 6th Airlanding Brigade, together with the 5th Parachute Brigade, was concerned with the first and fourth tasks given above, whilst the 3rd Parachute Brigade’s role covered the second, third and also the fourth. Map 3 gives the dropping zones and landing zones.

The role of the 6th Airlanding Brigade, which consisted of the 52nd, 1st Battalion The Royal Ulster Rifles and the 12th Battalion The Devonshire Regiment, was to occupy the southern flank of the divisional perimeter. The Royal Ulster Rifles were to seize Ste Honorine and the 52nd Escoivile. The 12th Devons were to occupy a feature in the centre known as Ring Contour 72. These positions were to be secured by the day after D Day. In addition, the 52nd was given the most important task of providing a coup-de-main force of six platoons whose fortunes have already been described.

The division was to be carried to Normandy in two lifts. The parachute brigades and the 52nd coup-de-main force were to leave on the night before D Day, followed by divisional headquarters and divisional troops. The 52nd, together with the Royal Ulsters, were in the second flight, due to leave Engiand on the afternoon of D Day. The other battalion of the airlanding brigade, the 12th Devons, had to join the seaborne invasion owing to shortage of aircraft.

Excellent briefing facilities were available, in the first instance, for company commanders in the secret briefing rooms, and, secondly, for all members of the Regiment at a later stage when on the airfields. The country over which we were to operate could be studied in minute detail with the aid of beautifully constructed cloth models which showed detail down to hedgerows and individual buildings. Air photographs taken up to the last moment enabled us to plan down to the very location of section posts in Escoville should we arrive there as planned.

Situation maps gave the latest information of enemy localities, defences and troop movements. A guide book gave a wealth of local information. We were therefore able to study the ground and our opponent’s moves, trace the defences of the 711th and 716th German Infantry Divsions in our battle area, watch the movements of the German counter-attack divisions, and, for instance, note and wonder at the sudden move of the 21st Panzer Division to the Caen area. Did the enemy know where we were to land? If not, why had the panzer division moved? And why were anti-glider landing poles being erected in the areas where our landing zones were planned?

Training continued up to the last available day. The intricate plans for each glider load were worked out, weapons, equipment, vehicles and kits checked and rechecked, and then, a few days before D Day. Bulford saw us no more and we moved to concentration areas on the airfields from which we were to fly into battle.

The last parade and the move to the airfields differed little from the parades we had held so many times before going on exercises. Perhaps a certain tension and finality in the tone of C.S.M. Belcher’s voice, as he reported Letter C Company present, echoed all our feelings that at long last we were really off to face our unknown destinies.

The 52nd moved to sealed camps at Tarrant Rushton, Harwell and Keevil

airfields. Those of us at Harwell thought it a good omen that we were to depart from Oxfordshire.

However, the particular stubble field, surrounded by a barbed-wire fence, across the road from the airfield was not one of the county’s choicer spots. In this camp we were completely sealed from the outside world, no contact whatsoever being allowed with anyone not in the Regiment, and no one being allowed beyond the barbed-wire perimeter, except the loading parties, which were closely shepherded to the glider parking area on the airfield.

The time spent in the concentration camps was not wasted. Intensive briefing was done with the aid of the models and photographs that had been set up in the huts in the camp. Every soldier was put in the picture fully and shown the ground over which he would fight. Particular study was made of the village of Escoville and its approaches, for this was our ultimate objective. The ground in the area of our landing zone was also care-fully scrutinized so that landmarks could be picked up if gliders went astray. The intense desire by all ranks for knowledge of the operation and of the area of operations was perhaps natural, but it was a comfort to see such enthusiasm.

Whilst in the concentration area we were issued with our escape kits which

included silk maps, compasses, hard rations, hacksaw blades, money, magnetic buttons and even fishing hooks. Men of the Regiment vied with each other in ingenuity for concealment of the items in their clothing. One soldier remarked that he had never had magnetic fly buttons before and wondered what effect they might have. Company commanders had to sign for large amounts of liberation francs, to be used only in an emergency, and we wondered if an equivalent amount would be added to our overdrafts if they were lost or improperly used.

Two days before D Day equipment and vehicles were loaded into our gliders. The lashings were checked and checked again, for we were fully aware of the dangers of loose or runaway equipment in a glider.

All was now ready for the big event, but the weather had intervened and it was not till the 5th June, 1944, that we heard that we would go on the

morrow.

That evening a small party from Regimental headquarters visited Tarrant Rushton airfield to see the take-off of the coup de-main party commanded by Major R J. Howard. They were in excellent heart and looked very impressive with their blackened faces, airborne helmets and clothing already camouflaged. They were airborne at about 2130 hrs on the 5th June, and so began the 52nd’s part in the great assault of the 6th June, 1944. with the 52nd taking the honour by providing, in the coup-de-main force, the first fighting troops to land in Europe.

Meanwhile we at Harwell bade au revoir to the first glider lift. Included in this party was our small advanced party, led by Major M. M. Darell-Brown. He was, however unsuccessful in reaching Europe at his first attempt, as his giider made a forced landing in England and we were more than surprised to find him having an early breakfast the next morning. He was even less talkative than usual at such an hour.

The day of D Day (6th June, 1944) was spent in final checks and company commanders attended the R.A.F. briefing of tug aircraft and glider pilots, and listened to technical details for the flight, cast-off and landing. The cheerful approach by the R.A.F. to the operation was very encouraging and the meteorological officer got his usual laugh. We were then asked to give the pilots an outline of our company tasks, in which the pilots showed great interest. Every spare moment of the day was spent with ears glued to the wireless. The broadcasts in both French and English on that June morning will long be remembered by those who knew that before long they too would be joining in the “grand debarquement des Allies.”

It was with few regrets that, after tea on the 6th June, we left our camp and moved to the airfield. An impressive array of Horsa gliders lined up on the edge of the runway awaited us. A brief command and we split up into our glider parties and waited for the order to emplane. The impression I got was that the men were quiet, but confident and keen to get on with the job. Such laughter as there was seemed slightly forced and directed mainly at remarks, some rude, some humorous, chalked on the fuselages of the gliders. At about 1830 hrs. with final wishes of bon voyage over, we were in our gliders. In the glider we all wore Mae Wests and had a rapid rehearsal of our ditching drill in case we pranged (This is believed to be current slang in the R.A.F. for crashed or forced to land) in the English Channel. Then with safety belts adjusted we waited for the jerk as the tug took the strain on the tow rope. Soon it came and those in the front seats could see themselves hurtling down the smooth runway behind of the tug. Then we were airborne and once again we heard the familiar whistle as the air rushed by and we glided higher and higher into the evening sky. The first hour of flying was spent in moving to a rendezvous over the south coast of England and then in taking up position in the air armada which was quickly forming for France.

Once inside a Horsa glider, except for a person standing in the hatchway leading into the pilot’s cockpit, the view outside is restricted. Small portholes allow a limited vision to either side, but little can be seen except sky and an occasional glimpse of the nearer tugs and gliders. This soon becomes boring and it was interesting to note the reactions of one’s fellow-passengers. Most were soon asleep. This was the usual reaction on long practice flights and even the excitement of our present flight could not break the old hands of the remarkable aptitude of the British soldier for sleep. Others were reading newspapers and an occasional song was hummed. The only two persons looking in any way perturbed were two men of the Corps of Military Police who were flying with us. They were really parachutists, it was their first flight in a glider, and they obviously missed their parachutes. Glider troops carry no parachutes.

The air fleet eventually passed over the coast in the Portsmouth area and headed across the sea. For a short time we were out of sight of land and could only see silvery dots which were ships on the sea below. The sea appeared calm. Our fighter escort was by now weaving and turning above and around us. One could not help wondering whether all the planes sweeping to and fro were’friendly. A glider is very helpless if attacked in the air and, although we had been told to fire Brens through the glider’s portholes in the event of air attack, we were not too confident of ou prowess as air gunners. Events proved that all aircraft sighted were friendly.

Very soon the French coast came into sight. We had dropped altitude to about 3,000 feet and it was soon possible to see ahead of us the mass of shipping off the beaches. There seemed to be thousands of ships of every shape and size. Beyond the ships the yellow line of the beaches stretched out to our right and left, with the green and yellow fields of Normandy forming the background.

Haze and smoke prevented, at this stage, the identification of any landmarks, but once over the coastline it was possible to pick out the line of the River Orne and out ahead the town of Caen.

Our navigator had not failed us: we had arrived.

The thoughts of all those in a position to get a view of the ground below must have been the same. Where was our landing zone? Would the pilots find it? Would it be free of enemy? Would it be clear of the anti-glider landing poles?

Suddenly one of the glider pilots pointed below, and there was the landing zone. A moment later he made another motion with his hand as puffs of black smoke began to appear in the sky, followed by the cracking thuds so well known to war-time airmen. It was flak (German for anti-aircraft fire) the enemy was somewhere below us. Then came the moment for cast-off. I noticed the sweat breaking out on the necks of the glider pilots and with a muttered “Here we go we were clear of our tug and had begun our slow spiral descent to earth. The time was about 2130 hrs. Glancing back into the body of the glider, C Company headquarters staff were sitting stiffly in the seats. It must have been an ordeal for them, being unable to see what was happening. No one had been hit by flak and a quick “We’re O.K.” brought relief to the faces of those I could see.

Looking again over the glider pilot’s shoulder I could see the first gliders about to land. They seemed to be coming in from all angles and as we approached to land the language of the pilots became unprintable. The landing plan was obviously not working with the precision expected. In order to avoid a mid air collision our senior glider pilot made a split-second decision to land just off the actual landing zone. Leaning forward to place my arms in a protective position around my head, I felt the glider touch down and saw that we were making straight towards a large hedge. An almighty crash and splintering of wood followed, then silence and the glider had stopped.

Our landing drill worked and all-round defence around the glider was at once adopted. Our glider no longer had any wheels, wings or tail, otherwise it seemed undamaged, although we had ploughed a lane through a large hedge.

No one was the worse for the experience except for a few bruises. The jeeps and other equipment were being unloaded and the signaller was struggling to re-net the somewhat shaken wireless sets.

This landing was typical of many landings: some were better, some much worse. In fact, all the gliders of the Regiment, except four, landed in or near the landing zone, and in spite of the many crash landings and collisions that took place our casualties were small.

The position on the landing zone was rather obscure. Firing was going on in the area of Benouville, chosen as the Regimental rendezvous, and there was also a certain amount of firing on the landing zone itself. One glider ended up in an enemy slit trench, the occupants of which quickly surrendered, being quite unnerved by the sudden descent of a large number of gliders on their position.

The adjutant, doctor and serjeant-major were rather astonished to find a real live German about ten yards from them when they leapt from their glider. After a certain amount of fumbling for weapons they succeeded in taking their first prisoner.

After a certain amount of delay, during which time enemy were cleared out of Benouville by a battalion of the 3rd Infantry Division and ourselves, the

Regiment assembled as arranged just west of the River Orne and at 2215 hrs began to move to the prearranged concentration area east of the River Orne. Four of our gliders were still missing. These contained a platoon of Letter B Company, a detachment of the mortar platoon and the intelligence officer’s party. It was ‘learned later that they had landed in England and Lieutenant R. M. Osborne joined us the next day, having travelled by sea. Of the officers injured on the landing zone the assistant adjutant, Lieutenant L. Nicholson, had to be evacuated, but the commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel M. W. Roberts, was able to carry on for a time, although injured when his glider came into collision with another glider whilst still some ten feet from the ground.

The situation in the divisional bridgehead area when the 52nd landed was as follows: 7th Parachute Battalion was in position holding an area west of the River Orne bridges. The remainder of the 5th Parachute Brigade (12th and 13th Battalions) were holding the bridgehead to the south-east of the bridges in the Bas de Ranville—Ranville—Ranville le Mariquet area.

The 3rd Parachute Brigade, having destroyed the German coastal battery south of Merville and the bridges over the River Dives, was operating on an approximate line Hauger—Le Mesnil—Bois de Bavent.

The 1st Special Service Brigade was fighting its way towards Sallenelles. All battalions had had very heavy fighting during the day against heavy German pressure on the bridgehead. By 2300 hrs on the 6th June the 52nd was concentrated east of the River Orne. The move to the area was uneventful except that the night was dark and our move coincided with a supply drop in the area by the R.A.F.

Large hampers full of stores were falling to the ground close to our route and occasionally the parachutes failed to open and the threat from a “free drop” hamper seemed worse than the odd enemy shell. When passing over the Orne bridges we learnt first hand of the brilliant success of our coup-de-main party.

Major John Howard met the commanding officer on the bridges as we passed over. It was, however, sad to hear of the first 52nd casualties, particularly the death of Lieutenant Den Brotheridge, who was killed at the head of his platoon in its gallant assault on the western end of the bridge.

From the concentration area the Regiment was ordered forward at 0130 hrs to the area of the chateau at Ranville with orders to go forward to Herouvillette at first light. At Ranville companies took up all-round defence positions in the chateau grounds. The 13th Parachute Battalion was holding this area and had had a tough time since landing the previous evening. Lieutenant-Colonel P. J. Luard, their commanding officer, was, however, in good heart and told us that they had been in contact with the enemy till darkness had fallen. He thought that Herouvillette was held by the enemy.

During the early hours of the morning of the 7th June C Company sent a fighting patrol into Herouvillette but found the it deserted. At Ranville the coup-de-main force returned to the Regiment. Captain B. C. E. Priday and his glider party also turned up. 1

1. The Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry Chronicle, Vol 4: June 1944 - December 1945 Pages 71-81

Proudly powered by Weebly