- HOME

- SOLDIER RESEARCH

- WOLVERTONS AMATEUR MILITARY TRADITION

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE RIFLE VOLUNTEERS 1859-1908

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BATTALION 1908-1947

- The Bucks Battalion A Brief History

- REGIMENTAL MARCH

-

1ST BUCKS 1914-1919

>

- 1914-15 1/1ST BUCKS MOBILISATION

- 1915 1/1ST BUCKS PLOEGSTEERT

- 1915-16 1/1st BUCKS HEBUTERNE

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS SOMME JULY 1916

- 1916 1/1st BUCKS POZIERES WAR DIARY 17-25 JULY

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS SOMME AUGUST 1916

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS LE SARS TO CAPPY

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS THE GERMAN RETIREMENT

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS TOMBOIS FARM

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS THE HINDENBURG LINE

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS 3RD BATTLE OF YPRES

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES 16th AUGUST

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES WAR DIARY 15-17 JULY

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS 3RD BATTLE OF YPRES - VIMY

- 1917-18 1/1ST BUCKS ITALY

-

2ND BUCKS 1914-1918

>

- 1914-1916 2ND BUCKS FORMATION & TRAINING

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS ARRIVAL IN FRANCE

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS FROMELLES

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS REORGANISATION

- 1916-1917 2/1st BUCKS THE SOMME

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS THE GERMAN RETIREMENT

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS ST QUENTIN APRIL TO AUGUST 1917

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS ARRAS & CAMBRAI

- 1918 2/1st BUCKS ST QUENTIN TO DISBANDMENT

-

1ST BUCKS 1939-1945

>

- 1939-1940 1BUCKS MOBILISATION & NEWBURY

- 1940 1BUCKS FRANCE & BELGIUM

- 1940 1BUCKS HAZEBROUCK

- HAZEBROUCK BATTLEFIELD VISIT

- 1940-1942 1BUCKS

- 1943-1944 1BUCKS PREPARING FOR D DAY

- COMPOSITION & ROLE OF BEACH GROUP

- BROAD OUTLINE OF OPERATION OVERLORD

- 1944 1ST BUCKS NORMANDY D DAY

- 1944 1BUCKS 1944 NORMANDY TO BRUSSELS (LOC)

- Sword Beach Gallery

- 1945 1BUCKS 1945 FEBRUARY-JUNE T FORCE 1st (CDN) ARMY

- 1945 1BUCKS 1945 FEBRUARY-JUNE T FORCE 2ND BRITISH ARMY

- 1945 1BUCKS JUNE 1945 TO AUGUST 1946

- BUCKS BATTALION BADGES

- BUCKS BATTALION SHOULDER TITLES 1908-1946

- 1939-1945 BUCKS BATTALION DRESS >

- ROYAL BUCKS KINGS OWN MILITIA

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE'S LINE REGIMENTS

- ROYAL GREEN JACKETS

- OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1965

- OXF & BUCKS LI INSIGNIA >

- REGIMENTAL CUSTOMS & TRADITIONS >

- REGIMENTAL COLLECT AND PRAYER

- OXF & BUCKS LI REGIMENTAL MARCHES

- REGIMENTAL DRILL >

-

REGIMENTAL DRESS

>

- REGIMENTAL UNIFORM 1741-1896

- REGIMENTAL UNIFORM 1741-1914

- 1894 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1897 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1900 DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1931 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1939-1945 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1950 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1960 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS (TA)

- 1960 REGIMENTAL MESS DRESS

- 1963 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1958-1969 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- HEADDRESS >

- REGIMENTAL CREST

- BATTLE HONOURS

- REGIMENTAL COLOURS >

- BRIEF HISTORY

- REGIMENTAL CHAPEL, OXFORD >

-

THE GREAT WAR 1914-1918

>

- REGIMENTAL BATTLE HONOURS 1914-1919

- OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY INTRODUCTION

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY

- 1/4 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 2/4 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 1/1 BUCKS BATTALION 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 2/1 BUCKS BATTALION 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 5 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 6 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 7 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 8 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 1st GREEN JACKETS (43rd & 52nd) 1958-1965

- 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND) 1958-1965

- 1959 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1959 REGIMENTAL MARCH IN OXFORD

- 1959 DEMONSTRATION BATTALION

- 1960 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1961 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1961 THE LONGEST DAY

- 1962 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1963 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1963 CONVERSION TO “RIFLE” REGIMENT

- 1964 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1965 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1965 FORMATION OF ROYAL GREEN JACKETS

- REGULAR BATTALIONS 1741-1958

-

1st BATTALION (43rd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

-

43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1914

>

- 43rd REGIMENT 1741-1802

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1803-1805

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1806-1809

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1809-1810

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1810-1812

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1812-1814

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1814-1818

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1818-1854

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1854-1863

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1863-1865

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1865-1897

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1899-1902

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1902-1914

-

1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919

>

-

1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1920-1939

>

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1920

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1921

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1922

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1923

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1924

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1925

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1926

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1927

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1928

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1929

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1930

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1931

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1932

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1933

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1934

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1935

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1936

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1937

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1938

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1939

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945 >

-

1 OXF & BUCKS 1946-1958

>

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1946

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1947

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1948

- 1948 FREEDOM PARADES

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1949

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1950

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1951

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1952

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1953

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1954

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1955

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1956

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1957

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1958

-

43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1914

>

-

2nd BATTALION (52nd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

- 52nd LIGHT INFANTRY 1755-1881 >

- 2 OXF LI 1881-1907

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1908-1914

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919

>

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919-1939

>

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1920

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1921

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1922

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1923

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1924

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1925

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1926

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1927

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1928

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1929

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1930

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1931

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1932

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1933

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1934

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1935

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1936

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1937

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1938

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1939

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945

>

- 1939-1941

- 1941-1943 AIRBORNE INFANTRY

- 1944 PREPARATION FOR D DAY

- 1944 PEGASUS BRIDGE-COUP DE MAIN

- Pegasus Bridge Gallery

- Horsa Bridge Gallery

- COUP DE MAIN NOMINAL ROLL

- MAJOR HOWARDS ORDERS

- 1944 JUNE 6

- D DAY ORDERS

- 1944 JUNE 7-13 ESCOVILLE & HEROUVILETTE

- Escoville & Herouvillette Gallery

- 1944 JUNE 13-AUGUST 16 HOLDING THE BRIDGEHEAD

- 1944 AUGUST 17-31 "PADDLE" TO THE SEINE

- "Paddle To The Seine" Gallery

- 1944 SEPTEMBER ARNHEM

- OPERATION PEGASUS 1

- 1944/45 ARDENNES

- 1945 RHINE CROSSING

- OPERATION VARSITY - ORDERS

- OPERATION VARSITY BATTLEFIELD VISIT

- 1945 MARCH-JUNE

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI DRESS 1940-1945 >

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1946-1947 >

-

1st BATTALION (43rd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

- MILITIA BATTALIONS

- TERRITORIAL BATTALIONS

- WAR RAISED/SERVICE BATTALIONS 1914-18 & 1939-45

-

5th, 6th, 7th & 8th (SERVICE) 1914-1918

>

-

6th & 7th Bns OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945

>

- 6th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI 1940-1945 >

-

7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI 1940-1945

>

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1940-JULY 1942

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JULY 1942 – JUNE 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JULY 1943–OCTOBER 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI OCTOBER 1943–DECEMBER 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI DECEMBER 1943-JUNE 1944

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JANUARY 1944-JUNE 1944

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1944–JANUARY 1945

-

5th, 6th, 7th & 8th (SERVICE) 1914-1918

>

- "IN MY OWN WORDS"

- CREDITS

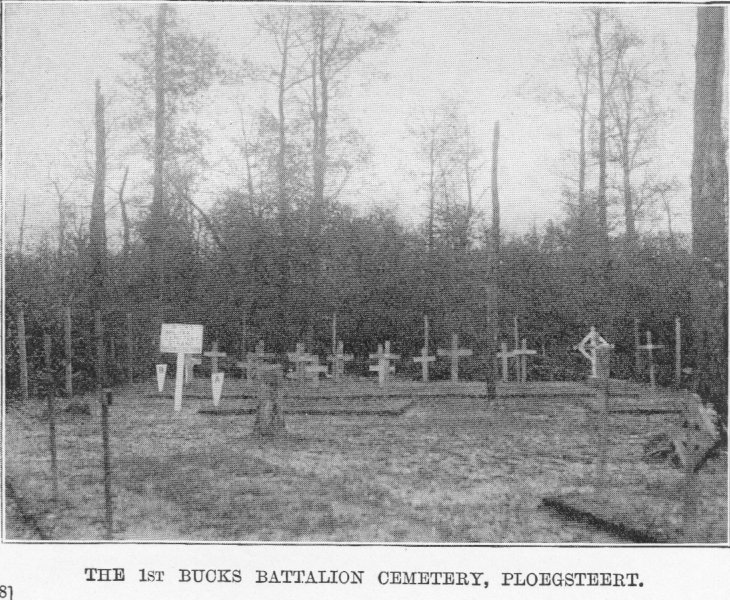

FIRST BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BATTALION

PLOEGSTEERT

March to June 1915

BASED ON EXTRACTS FROM CITIZEN SOLDIERS OF BUCKS BY JC SWANN AND THE FIRST BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BATTALION 1914-1919 BY PL WRIGHT

At 3.30 p.m. on March 31, 1915, the Battalion paraded and marched down another tortuous road to Pont de Briques, where it entrained in a French troop train. It consisted of some twenty cattle-trucks, each marked to hold between forty and fifty men. The battalion nicknamed the engine “Puffing Billy”

After some five hours of this very crowded travelling, the battalion arrived at Cassel, and detrained at 11 p.m. A three hour march brought it to Terdeghem, where its billets lay. Accommodation being very scanty, many spent the warm night in the open. The wind changed during that night, with the result that the sound of the guns were heard for the first time in the morning.

For three nights the battalion remained at Terdeghem, the only event of importance being an inspection on April 2 of the Brigade at Steenvoorde by General Sir H. Smith-Dorrien, who was at that time commanding the 2nd Army. The battalion then moved to billets on the Outtersteene-Bailleul Road (S.E. of Meteren), where two more nights were spent.

On the 7th April the Battalion marched via Bailleul and Armentieres to Le Bizet, where all the Companies were attached to Units of the 4th Division (2nd Monmouthshire Regiment, 2nd Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers, 2nd Battalion Essex Regiment) for instruction in the method of holding trenches.

Sniping was active, and the Germans were no mean shots at the 50 to 150 yards which separated their trenches from ours.

On the morning of the second day, April 9, the 4th Division exploded a mine under the enemy trenches. The enemy retaliated by shelling our line. One shell entered and burst inside the remains of an old house, containing A Company headquarters. By a miracle everyone escaped unhurt, though many of their possessions were never seen again.

The attachment for instruction lasted four days, two of which were spent in the front line, and two in support. After four days’experience the Battalion was considered ready to take its place in the line on its own.

On April 12, the Battalion marched to billets at Steenwerck, some eight miles distant.

On the 14th the Commanding Officer, Adjutant and company commanders received orders to reconnoitre the line with a view to the Battalion relieving the 1st Battalion Somersetshire Light Infantry, who were in support in Ploegsteert Wood.

On the 15th the battalion marched to Ploegsteert, relieving the 1st Battalion

Somerset Light Infantry.

Life during the next two months, were were spent at Ploegsteert or in billets at Romarin.

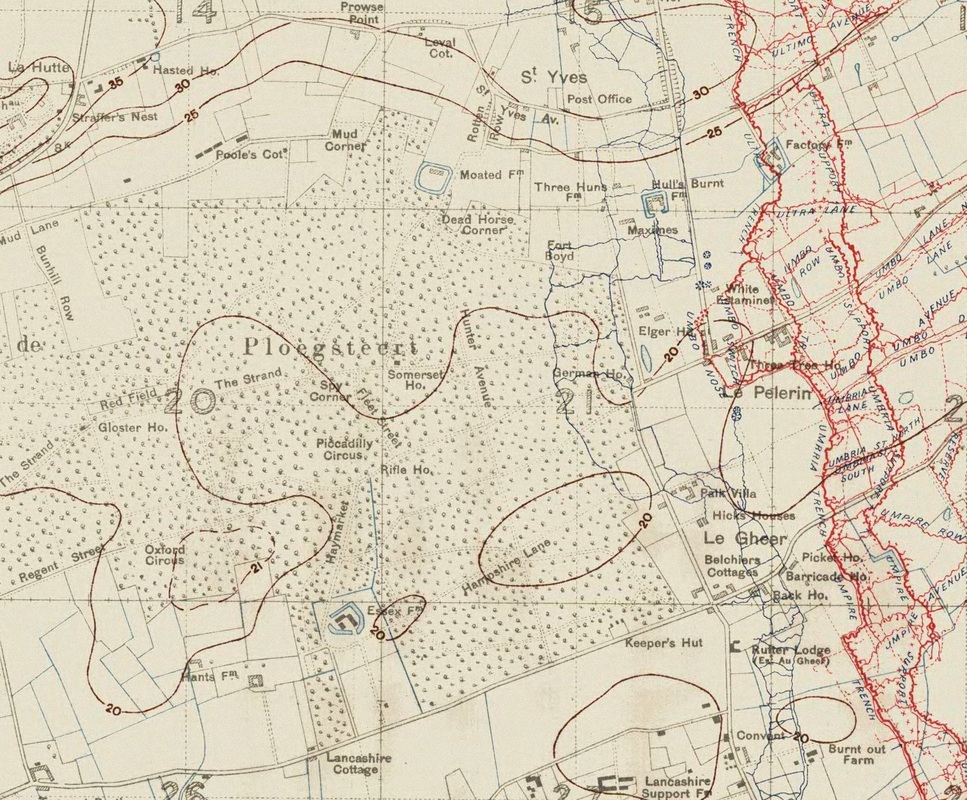

The trees had been damaged very little, and the fresh green foliage and undisturbed bird life made it most difficult to believe in the existence of a war. Paths had been cleared in all useful directions through the wood, and duck-board tracks laid down to prevent the paths becoming mud channels in wet weather. The majority of these tracks were known by London names, such as The Strand, Rotten Row, Hyde Park Corner, but here and there names like “Dead Horse Corner” appeared. All the houses behind our lines had names, those which received the most attention from the German gunners being the best known: Hull’s Burnt Farm, Three Huns, St. Yves Post Office, are names which conjure up innumerable memories.

The trenches most frequently held by the Battalion in this area were situated in front of the village of St. Yves, the line being held with three companies in the firing line and one in support. The 1/5th Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment relieved the battalion every four days, moving either into the wood or back to billets at Romarin.

The trenches consisted of sandbagged walls, a duck-board bottom, a host of large flies and an enormous smell.

The fire trench ran about 200 yards from the German front line, though in places the two trenches approached to within 100 yards of each other. To show one’s head over the top of the parapet was therefore risky, in view of the enemy snipers, who were really first-rate shots and always on the look-out for a target. Desultory rifle fire was kept up by both sides throughout the twenty-four hours, always increasing in volume at “stand to,”each morning and evening, and generally reaching the most absurd pitch about one hour after darkness.

The Battalion remained in this sector till the 27th June, generally holding the trenches in front of the village of St. Yves with three Companies in the

firing-line and one in support.

Every four days the 1/5th Gloucester Regiment moved up in relief, the Battalion going back to Romarin to rest billets.

During this period the sector was comparatively quiet, and there was little or no shelling. There were, however, a considerable number of casualties from grenades and snipers. Very little training was carried out, but the Battalion was finding its feet and getting accustomed to trench warfare, acquiring a great deal of experience of field engineering, and last, but not least, gaining considerable knowledge of the art of making uncomfortable conditions more or less comfortable.

On occasions when anything in the nature of an attack was taking place on some other part of the front, orders were received to make a demonstration. The demonstration would be carried out by all units who happened to be holding the Divisional front.

9 a.m.—Long-range rifle fire directed on roads in rear of enemy trenches.

11 a.m.—Artillery bombard a certain section or sections of enemy trench with the object of breaching their parapet.

11.05 a.m.—Whole of front-line garrison open five minutes’ rapid fire on German front line.

1.45 p.m.—A few rifle grenades fired by companies within range of enemy.

4.15 p.m.—A trench mortar fired; three rifle grenades fired at same time from either side of it.

6.15 p.m.—Long-range rifle fire directed on roads in rear.

The enemy seldom paid the smallest attention to these demonstrations, except possibly by spending five minutes in flooding our trench with rifle

grenades.

The last period spent in the line in these parts was in the Douve trenches facing Messines, after which began on June 24 a four-day march to other

climes.

Since landing in France 5 officers had been wounded, 9 other ranks had been killed and 59 wounded.

In the middle of June, owing to illness, Major-General H. N. C. Heath, C.B., handed over command of the Division to Major-General R. Fanshawe, C.B., D.S.O. (52nd L.I.).

PLOEGSTEERT

March to June 1915

BASED ON EXTRACTS FROM CITIZEN SOLDIERS OF BUCKS BY JC SWANN AND THE FIRST BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BATTALION 1914-1919 BY PL WRIGHT

At 3.30 p.m. on March 31, 1915, the Battalion paraded and marched down another tortuous road to Pont de Briques, where it entrained in a French troop train. It consisted of some twenty cattle-trucks, each marked to hold between forty and fifty men. The battalion nicknamed the engine “Puffing Billy”

After some five hours of this very crowded travelling, the battalion arrived at Cassel, and detrained at 11 p.m. A three hour march brought it to Terdeghem, where its billets lay. Accommodation being very scanty, many spent the warm night in the open. The wind changed during that night, with the result that the sound of the guns were heard for the first time in the morning.

For three nights the battalion remained at Terdeghem, the only event of importance being an inspection on April 2 of the Brigade at Steenvoorde by General Sir H. Smith-Dorrien, who was at that time commanding the 2nd Army. The battalion then moved to billets on the Outtersteene-Bailleul Road (S.E. of Meteren), where two more nights were spent.

On the 7th April the Battalion marched via Bailleul and Armentieres to Le Bizet, where all the Companies were attached to Units of the 4th Division (2nd Monmouthshire Regiment, 2nd Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers, 2nd Battalion Essex Regiment) for instruction in the method of holding trenches.

Sniping was active, and the Germans were no mean shots at the 50 to 150 yards which separated their trenches from ours.

On the morning of the second day, April 9, the 4th Division exploded a mine under the enemy trenches. The enemy retaliated by shelling our line. One shell entered and burst inside the remains of an old house, containing A Company headquarters. By a miracle everyone escaped unhurt, though many of their possessions were never seen again.

The attachment for instruction lasted four days, two of which were spent in the front line, and two in support. After four days’experience the Battalion was considered ready to take its place in the line on its own.

On April 12, the Battalion marched to billets at Steenwerck, some eight miles distant.

On the 14th the Commanding Officer, Adjutant and company commanders received orders to reconnoitre the line with a view to the Battalion relieving the 1st Battalion Somersetshire Light Infantry, who were in support in Ploegsteert Wood.

On the 15th the battalion marched to Ploegsteert, relieving the 1st Battalion

Somerset Light Infantry.

Life during the next two months, were were spent at Ploegsteert or in billets at Romarin.

The trees had been damaged very little, and the fresh green foliage and undisturbed bird life made it most difficult to believe in the existence of a war. Paths had been cleared in all useful directions through the wood, and duck-board tracks laid down to prevent the paths becoming mud channels in wet weather. The majority of these tracks were known by London names, such as The Strand, Rotten Row, Hyde Park Corner, but here and there names like “Dead Horse Corner” appeared. All the houses behind our lines had names, those which received the most attention from the German gunners being the best known: Hull’s Burnt Farm, Three Huns, St. Yves Post Office, are names which conjure up innumerable memories.

The trenches most frequently held by the Battalion in this area were situated in front of the village of St. Yves, the line being held with three companies in the firing line and one in support. The 1/5th Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment relieved the battalion every four days, moving either into the wood or back to billets at Romarin.

The trenches consisted of sandbagged walls, a duck-board bottom, a host of large flies and an enormous smell.

The fire trench ran about 200 yards from the German front line, though in places the two trenches approached to within 100 yards of each other. To show one’s head over the top of the parapet was therefore risky, in view of the enemy snipers, who were really first-rate shots and always on the look-out for a target. Desultory rifle fire was kept up by both sides throughout the twenty-four hours, always increasing in volume at “stand to,”each morning and evening, and generally reaching the most absurd pitch about one hour after darkness.

The Battalion remained in this sector till the 27th June, generally holding the trenches in front of the village of St. Yves with three Companies in the

firing-line and one in support.

Every four days the 1/5th Gloucester Regiment moved up in relief, the Battalion going back to Romarin to rest billets.

During this period the sector was comparatively quiet, and there was little or no shelling. There were, however, a considerable number of casualties from grenades and snipers. Very little training was carried out, but the Battalion was finding its feet and getting accustomed to trench warfare, acquiring a great deal of experience of field engineering, and last, but not least, gaining considerable knowledge of the art of making uncomfortable conditions more or less comfortable.

On occasions when anything in the nature of an attack was taking place on some other part of the front, orders were received to make a demonstration. The demonstration would be carried out by all units who happened to be holding the Divisional front.

9 a.m.—Long-range rifle fire directed on roads in rear of enemy trenches.

11 a.m.—Artillery bombard a certain section or sections of enemy trench with the object of breaching their parapet.

11.05 a.m.—Whole of front-line garrison open five minutes’ rapid fire on German front line.

1.45 p.m.—A few rifle grenades fired by companies within range of enemy.

4.15 p.m.—A trench mortar fired; three rifle grenades fired at same time from either side of it.

6.15 p.m.—Long-range rifle fire directed on roads in rear.

The enemy seldom paid the smallest attention to these demonstrations, except possibly by spending five minutes in flooding our trench with rifle

grenades.

The last period spent in the line in these parts was in the Douve trenches facing Messines, after which began on June 24 a four-day march to other

climes.

Since landing in France 5 officers had been wounded, 9 other ranks had been killed and 59 wounded.

In the middle of June, owing to illness, Major-General H. N. C. Heath, C.B., handed over command of the Division to Major-General R. Fanshawe, C.B., D.S.O. (52nd L.I.).

Proudly powered by Weebly