- HOME

- SOLDIER RESEARCH

- WOLVERTONS AMATEUR MILITARY TRADITION

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE RIFLE VOLUNTEERS 1859-1908

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BATTALION 1908-1947

- The Bucks Battalion A Brief History

- REGIMENTAL MARCH

-

1ST BUCKS 1914-1919

>

- 1914-15 1/1ST BUCKS MOBILISATION

- 1915 1/1ST BUCKS PLOEGSTEERT

- 1915-16 1/1st BUCKS HEBUTERNE

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS SOMME JULY 1916

- 1916 1/1st BUCKS POZIERES WAR DIARY 17-25 JULY

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS SOMME AUGUST 1916

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS LE SARS TO CAPPY

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS THE GERMAN RETIREMENT

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS TOMBOIS FARM

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS THE HINDENBURG LINE

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS 3RD BATTLE OF YPRES

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES 16th AUGUST

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES WAR DIARY 15-17 JULY

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS 3RD BATTLE OF YPRES - VIMY

- 1917-18 1/1ST BUCKS ITALY

-

2ND BUCKS 1914-1918

>

- 1914-1916 2ND BUCKS FORMATION & TRAINING

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS ARRIVAL IN FRANCE

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS FROMELLES

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS REORGANISATION

- 1916-1917 2/1st BUCKS THE SOMME

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS THE GERMAN RETIREMENT

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS ST QUENTIN APRIL TO AUGUST 1917

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS ARRAS & CAMBRAI

- 1918 2/1st BUCKS ST QUENTIN TO DISBANDMENT

-

1ST BUCKS 1939-1945

>

- 1939-1940 1BUCKS MOBILISATION & NEWBURY

- 1940 1BUCKS FRANCE & BELGIUM

- 1940 1BUCKS HAZEBROUCK

- HAZEBROUCK BATTLEFIELD VISIT

- 1940-1942 1BUCKS

- 1943-1944 1BUCKS PREPARING FOR D DAY

- COMPOSITION & ROLE OF BEACH GROUP

- BROAD OUTLINE OF OPERATION OVERLORD

- 1944 1ST BUCKS NORMANDY D DAY

- 1944 1BUCKS 1944 NORMANDY TO BRUSSELS (LOC)

- Sword Beach Gallery

- 1945 1BUCKS 1945 FEBRUARY-JUNE T FORCE 1st (CDN) ARMY

- 1945 1BUCKS 1945 FEBRUARY-JUNE T FORCE 2ND BRITISH ARMY

- 1945 1BUCKS JUNE 1945 TO AUGUST 1946

- BUCKS BATTALION BADGES

- BUCKS BATTALION SHOULDER TITLES 1908-1946

- 1939-1945 BUCKS BATTALION DRESS >

- ROYAL BUCKS KINGS OWN MILITIA

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE'S LINE REGIMENTS

- ROYAL GREEN JACKETS

- OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1965

- OXF & BUCKS LI INSIGNIA >

- REGIMENTAL CUSTOMS & TRADITIONS >

- REGIMENTAL COLLECT AND PRAYER

- OXF & BUCKS LI REGIMENTAL MARCHES

- REGIMENTAL DRILL >

-

REGIMENTAL DRESS

>

- REGIMENTAL UNIFORM 1741-1896

- REGIMENTAL UNIFORM 1741-1914

- 1894 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1897 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1900 DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1931 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1939-1945 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1950 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1960 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS (TA)

- 1960 REGIMENTAL MESS DRESS

- 1963 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1958-1969 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- HEADDRESS >

- REGIMENTAL CREST

- BATTLE HONOURS

- REGIMENTAL COLOURS >

- BRIEF HISTORY

- REGIMENTAL CHAPEL, OXFORD >

-

THE GREAT WAR 1914-1918

>

- REGIMENTAL BATTLE HONOURS 1914-1919

- OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY INTRODUCTION

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY

- 1/4 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 2/4 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 1/1 BUCKS BATTALION 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 2/1 BUCKS BATTALION 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 5 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 6 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 7 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 8 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 1st GREEN JACKETS (43rd & 52nd) 1958-1965

- 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND) 1958-1965

- 1959 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1959 REGIMENTAL MARCH IN OXFORD

- 1959 DEMONSTRATION BATTALION

- 1960 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1961 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1961 THE LONGEST DAY

- 1962 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1963 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1963 CONVERSION TO “RIFLE” REGIMENT

- 1964 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1965 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1965 FORMATION OF ROYAL GREEN JACKETS

- REGULAR BATTALIONS 1741-1958

-

1st BATTALION (43rd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

-

43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1914

>

- 43rd REGIMENT 1741-1802

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1803-1805

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1806-1809

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1809-1810

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1810-1812

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1812-1814

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1814-1818

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1818-1854

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1854-1863

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1863-1865

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1865-1897

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1899-1902

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1902-1914

-

1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919

>

-

1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1920-1939

>

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1920

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1921

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1922

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1923

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1924

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1925

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1926

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1927

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1928

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1929

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1930

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1931

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1932

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1933

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1934

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1935

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1936

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1937

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1938

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1939

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945 >

-

1 OXF & BUCKS 1946-1958

>

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1946

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1947

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1948

- 1948 FREEDOM PARADES

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1949

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1950

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1951

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1952

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1953

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1954

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1955

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1956

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1957

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1958

-

43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1914

>

-

2nd BATTALION (52nd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

- 52nd LIGHT INFANTRY 1755-1881 >

- 2 OXF LI 1881-1907

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1908-1914

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919

>

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919-1939

>

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1920

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1921

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1922

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1923

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1924

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1925

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1926

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1927

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1928

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1929

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1930

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1931

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1932

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1933

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1934

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1935

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1936

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1937

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1938

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1939

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945

>

- 1939-1941

- 1941-1943 AIRBORNE INFANTRY

- 1944 PREPARATION FOR D DAY

- 1944 PEGASUS BRIDGE-COUP DE MAIN

- Pegasus Bridge Gallery

- Horsa Bridge Gallery

- COUP DE MAIN NOMINAL ROLL

- MAJOR HOWARDS ORDERS

- 1944 JUNE 6

- D DAY ORDERS

- 1944 JUNE 7-13 ESCOVILLE & HEROUVILETTE

- Escoville & Herouvillette Gallery

- 1944 JUNE 13-AUGUST 16 HOLDING THE BRIDGEHEAD

- 1944 AUGUST 17-31 "PADDLE" TO THE SEINE

- "Paddle To The Seine" Gallery

- 1944 SEPTEMBER ARNHEM

- OPERATION PEGASUS 1

- 1944/45 ARDENNES

- 1945 RHINE CROSSING

- OPERATION VARSITY - ORDERS

- OPERATION VARSITY BATTLEFIELD VISIT

- 1945 MARCH-JUNE

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI DRESS 1940-1945 >

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1946-1947 >

-

1st BATTALION (43rd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

- MILITIA BATTALIONS

- TERRITORIAL BATTALIONS

- WAR RAISED/SERVICE BATTALIONS 1914-18 & 1939-45

-

5th, 6th, 7th & 8th (SERVICE) 1914-1918

>

-

6th & 7th Bns OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945

>

- 6th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI 1940-1945 >

-

7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI 1940-1945

>

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1940-JULY 1942

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JULY 1942 – JUNE 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JULY 1943–OCTOBER 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI OCTOBER 1943–DECEMBER 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI DECEMBER 1943-JUNE 1944

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JANUARY 1944-JUNE 1944

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1944–JANUARY 1945

-

5th, 6th, 7th & 8th (SERVICE) 1914-1918

>

- "IN MY OWN WORDS"

- CREDITS

OPERATION VARSITY - CROSSING THE RIVER RHINE, MARCH, 1945

BASED ON EXTRACTS FROM THE REGIMENTAL WAR CHRONICLES OF THE OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY VOL4 1944-1945 1

PREPARATIONS

In February, 1945, the Regiment flew back to England, but Major Mason and a party of H.Q. Company drivers remained on the Continent to form a “land tail” for our next operation. The 6th Airborne Division returned to its home base at Bulford Camp and the Regiment went back to Wing Barracks, where Letter R Company had everything running as usual. Preparations to re-equip, reorganize and prepare for the next operation were begun immediately. No one knew when or what the next operation was to be, but it was obvious that it would be in the near future.

Early in March there were two full-scale divisional exercises in the area of Bury St. Edmunds. These were “Mush I” and “Mush II,” and were to practise the division in operating behind an enemy main defence line. They were, in fact, a rehearsal for the assault crossing of the River Rhine, though this was not divulged at the time.

On return to barracks from “Mush II” the commanding officer was given the warning order that the 6th Airborne Division would carry out an airborne operation in North-West Europe before the end of March. All troops were to move into concentration areas for the operation by the 20th March. The Regiment was allotted a concentration area at Birch airfield, near Colchester.

The Regiment was also warned that it would be required to operate on what was known as the “hard scale.” This meant that only about seventy gliders would be available, and consequently only really essential fighting troops and equipment could go into action by air. A great deal of hard work and detailed planning was then necessary in order to ensure that the best possible use was made of the gliders available.

R Company had to load and man a duplicate glider for each operational load in the Regiment. Thus if a glider containing a rifle platoon, a 3-inch mortar detachment, signals or anti-tank gun detachment came to grief on take-off for the operation, a fully prepared and briefed R Company glider, with a similar crew and equipment, would be immediately available to take its place and go on the operation.

Such motor transport, equipment and men of the Regiment which were not required for the initial assault landing, or could not be carried in the available gliders, were formed into a “sea tail.”The “sea tail” would cross to the Continent by boat, and with Major Mason’s “land tail” would rejoin the Regiment in the battle zone as soon as contact with ground forces was established. The sea and land tails were the equivalent of A and B Echelons.

At last the expected movement orders arrived from the 6th Airlanding Brigade. The “sea tail” moved off for a south coast port, and the remainder of the Regiment moved by road to Birch on the 19th March. This camp, in which the Regiment was sealed until taking off for the operations was a bleak, wired-in, hutted dispersal camp on the edge of the airfield. In order to maintain the secrecy so essential in airborne operations no orders or briefing were begun until the Regiment was safely sealed in this camp. Until this time, only the commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Darell-Brown, D.S.O., and the intelligence officer, Captain Cross, knew anything of the plan.

Full briefing began early on the 20th. Well-arranged briefing huts containing plaster models of the objective, all necessary maps and air photographs were ready prepared. First, all company commanders and specialist officers had the plan explained to them by the commanding officer, then the glider pilots were brought in and introduced, and all possible details of the fly-in and plan of attack were thoroughly discussed and settled. After this, company commanders made their plans, then all ranks were fully briefed on the operation.

THE OUTLINE SITUATION

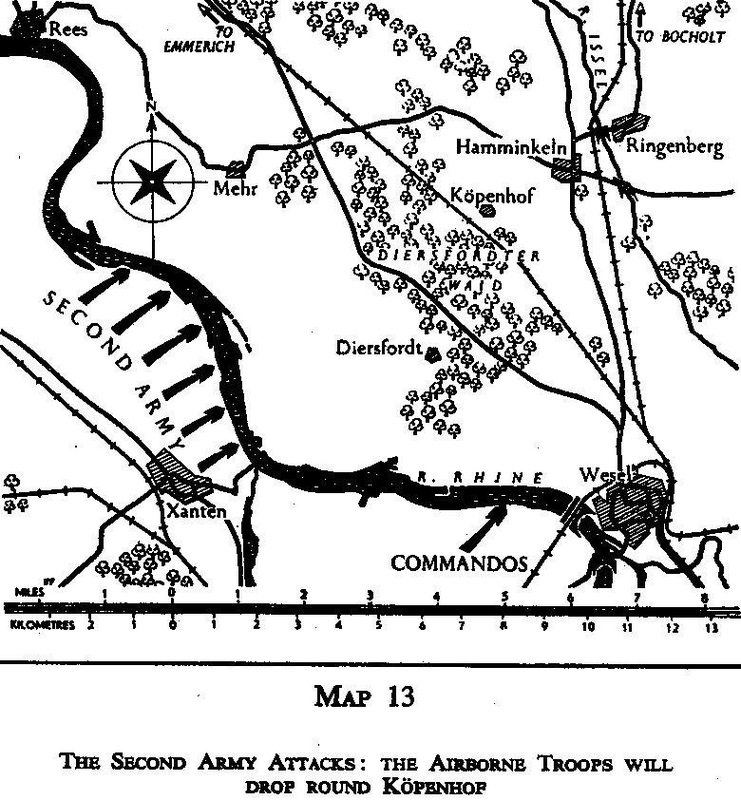

By March, 1945. the Germans had already all but lost the war in North-West Europe. However, they were apparently determined to fight it out to the end. They were then stubbornly defending their last great natural barriers, the Rhine in the west and the Oder in the east. In the east the Red Army of Soviet Russia had already established bridgeheads over the Oder, and were threatening Berlin from the south. In the west the Allies were poised along the line of the River Rhine, with the 21st Army Group, consisting of the Canadian First Army, British Second Army and United States Ninth Army, on the northern sector; the United States First, Third and Seventh Armies in the centre; and the French First Army in the South. In the centre the United States forces had already won a bridgehead over the river at Remagen.

The great industrial area of the Ruhr was to the east of the Rhine between the British and United States sectors of the front. Despite prolonged and heavy bombing, the war industries of the Ruhr were still working, and were of paramount importance to the continued existence of the German field forces. The Allied plan was to break across the Rhine north and south of the Ruhr, encircle and annihilate the enemy garrison, capture the Ruhr and at the same time advance to the east, defeating the remaining German forces in detail as quickly as possible. The British were to establish a bridgehead over the Rhine at Wesel, and break out eastwards to the north of the Ruhr, and the Americans were to break out from their bridgehead at Remagen south of the Ruhr. The two thrusts were planned to link up east of the Ruhr to encircle the garrison and to continue pressing eastwards.

XII Corps, of the British Second Army, was to make an assault crossing of the Rhine at Wesel on the night of the 23rd/24th March, and establish a bridgehead on the east bank.

XVIII Airborne Corps was then to land behind the main enemy defence line on the 24th March to disrupt the enemy defence, prevent enemy reinforcements reaching the area, and to enlarge the bridgehead so that an armoured break-out could be mounted without delay.

The programme of events on XII Corps front was as follows:

(a) 21st March

Allied air assaults to neutralize enemy airfields and anti-aircraft defences

(b) 23rd March

1730 hrs.: RAF. bomb Wesel (K52/A24).

1800 hrs.: Massed artillery programme begins softening-up enemy defences.

2200 hrs.: No. 1 Commando Brigade make silent crossing of the river and surround Wesel.

2230-2245 hrs.: RAF. to bomb Wesel on request.

(c) 24th March

0200 hrs.: XII Corps make assault crossing of Rhine at Wesel under artillery barrage. (Two divisions to the north and two divisions to the south of the town. Commando Brigade occupies Wesel.)

1000 hrs.: XVIII Airborne Corps land by parachute and glider in area of Haimminkeln (K52/A24) and Kopenhof (about five miles ahead of XII Corps).

1300 hrs.: Airborne troops to be resupplied by air.

(d) 25th March Ground troops link up with airborne troops.

BASED ON EXTRACTS FROM THE REGIMENTAL WAR CHRONICLES OF THE OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY VOL4 1944-1945 1

PREPARATIONS

In February, 1945, the Regiment flew back to England, but Major Mason and a party of H.Q. Company drivers remained on the Continent to form a “land tail” for our next operation. The 6th Airborne Division returned to its home base at Bulford Camp and the Regiment went back to Wing Barracks, where Letter R Company had everything running as usual. Preparations to re-equip, reorganize and prepare for the next operation were begun immediately. No one knew when or what the next operation was to be, but it was obvious that it would be in the near future.

Early in March there were two full-scale divisional exercises in the area of Bury St. Edmunds. These were “Mush I” and “Mush II,” and were to practise the division in operating behind an enemy main defence line. They were, in fact, a rehearsal for the assault crossing of the River Rhine, though this was not divulged at the time.

On return to barracks from “Mush II” the commanding officer was given the warning order that the 6th Airborne Division would carry out an airborne operation in North-West Europe before the end of March. All troops were to move into concentration areas for the operation by the 20th March. The Regiment was allotted a concentration area at Birch airfield, near Colchester.

The Regiment was also warned that it would be required to operate on what was known as the “hard scale.” This meant that only about seventy gliders would be available, and consequently only really essential fighting troops and equipment could go into action by air. A great deal of hard work and detailed planning was then necessary in order to ensure that the best possible use was made of the gliders available.

R Company had to load and man a duplicate glider for each operational load in the Regiment. Thus if a glider containing a rifle platoon, a 3-inch mortar detachment, signals or anti-tank gun detachment came to grief on take-off for the operation, a fully prepared and briefed R Company glider, with a similar crew and equipment, would be immediately available to take its place and go on the operation.

Such motor transport, equipment and men of the Regiment which were not required for the initial assault landing, or could not be carried in the available gliders, were formed into a “sea tail.”The “sea tail” would cross to the Continent by boat, and with Major Mason’s “land tail” would rejoin the Regiment in the battle zone as soon as contact with ground forces was established. The sea and land tails were the equivalent of A and B Echelons.

At last the expected movement orders arrived from the 6th Airlanding Brigade. The “sea tail” moved off for a south coast port, and the remainder of the Regiment moved by road to Birch on the 19th March. This camp, in which the Regiment was sealed until taking off for the operations was a bleak, wired-in, hutted dispersal camp on the edge of the airfield. In order to maintain the secrecy so essential in airborne operations no orders or briefing were begun until the Regiment was safely sealed in this camp. Until this time, only the commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Darell-Brown, D.S.O., and the intelligence officer, Captain Cross, knew anything of the plan.

Full briefing began early on the 20th. Well-arranged briefing huts containing plaster models of the objective, all necessary maps and air photographs were ready prepared. First, all company commanders and specialist officers had the plan explained to them by the commanding officer, then the glider pilots were brought in and introduced, and all possible details of the fly-in and plan of attack were thoroughly discussed and settled. After this, company commanders made their plans, then all ranks were fully briefed on the operation.

THE OUTLINE SITUATION

By March, 1945. the Germans had already all but lost the war in North-West Europe. However, they were apparently determined to fight it out to the end. They were then stubbornly defending their last great natural barriers, the Rhine in the west and the Oder in the east. In the east the Red Army of Soviet Russia had already established bridgeheads over the Oder, and were threatening Berlin from the south. In the west the Allies were poised along the line of the River Rhine, with the 21st Army Group, consisting of the Canadian First Army, British Second Army and United States Ninth Army, on the northern sector; the United States First, Third and Seventh Armies in the centre; and the French First Army in the South. In the centre the United States forces had already won a bridgehead over the river at Remagen.

The great industrial area of the Ruhr was to the east of the Rhine between the British and United States sectors of the front. Despite prolonged and heavy bombing, the war industries of the Ruhr were still working, and were of paramount importance to the continued existence of the German field forces. The Allied plan was to break across the Rhine north and south of the Ruhr, encircle and annihilate the enemy garrison, capture the Ruhr and at the same time advance to the east, defeating the remaining German forces in detail as quickly as possible. The British were to establish a bridgehead over the Rhine at Wesel, and break out eastwards to the north of the Ruhr, and the Americans were to break out from their bridgehead at Remagen south of the Ruhr. The two thrusts were planned to link up east of the Ruhr to encircle the garrison and to continue pressing eastwards.

XII Corps, of the British Second Army, was to make an assault crossing of the Rhine at Wesel on the night of the 23rd/24th March, and establish a bridgehead on the east bank.

XVIII Airborne Corps was then to land behind the main enemy defence line on the 24th March to disrupt the enemy defence, prevent enemy reinforcements reaching the area, and to enlarge the bridgehead so that an armoured break-out could be mounted without delay.

The programme of events on XII Corps front was as follows:

(a) 21st March

Allied air assaults to neutralize enemy airfields and anti-aircraft defences

(b) 23rd March

1730 hrs.: RAF. bomb Wesel (K52/A24).

1800 hrs.: Massed artillery programme begins softening-up enemy defences.

2200 hrs.: No. 1 Commando Brigade make silent crossing of the river and surround Wesel.

2230-2245 hrs.: RAF. to bomb Wesel on request.

(c) 24th March

0200 hrs.: XII Corps make assault crossing of Rhine at Wesel under artillery barrage. (Two divisions to the north and two divisions to the south of the town. Commando Brigade occupies Wesel.)

1000 hrs.: XVIII Airborne Corps land by parachute and glider in area of Haimminkeln (K52/A24) and Kopenhof (about five miles ahead of XII Corps).

1300 hrs.: Airborne troops to be resupplied by air.

(d) 25th March Ground troops link up with airborne troops.

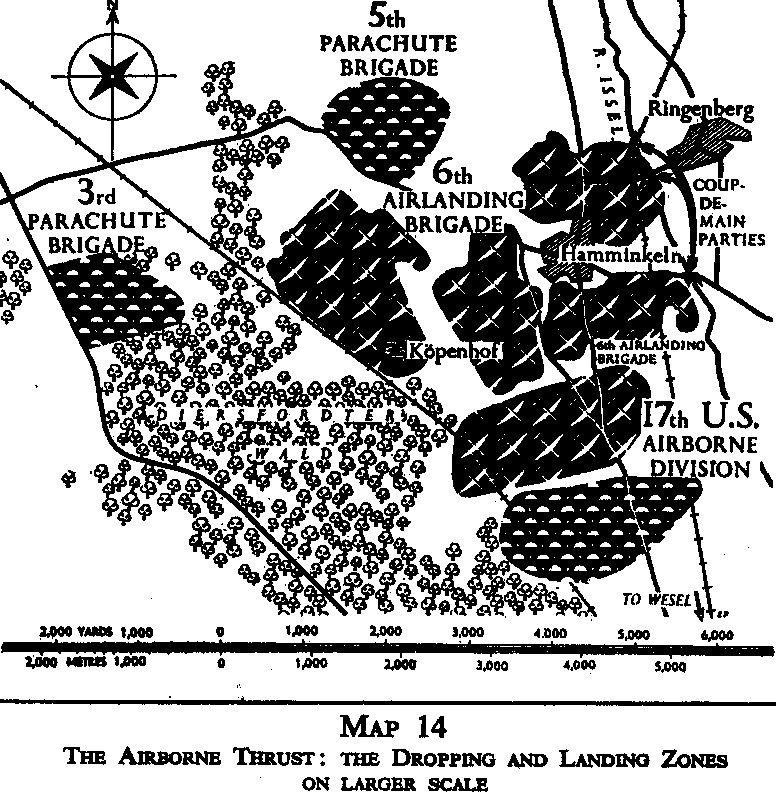

In this operation XVIII Airborne Corps was commanded by Major-General Ridgway, U.S. Army. It consisted of the United States 17th Airborne Division and the British 6th Airborne Division. The 17th Airborne Division was to fly from airfields in Belgium and France, and was to land south of the 6th Airborne Division, which was to fly in from airfields in England.

The 6th Airborne Division was commanded by Major-General Bols, and consisted of the 3rd Parachute Brigade, 5th Parachute Brigade and 6th Airlanding Brigade. These were supported by an airborne armoured reconnaissance regiment, the 53rd Airborne Light Regiment, Worcestershire Yeomanry, R.A., engineers and other airborne divisional troops. In addition the division would land within range of supporting fire from XII Corp medium artillery. Each of the brigades consisted of three battalions.

The whole of XVIII Airborne Corps was to be landed at the same time direct on to their objectives. The sectors allotted to the three brigades of the 6th Airborne Division and to the 17th U.S. Airborne Division are shown in the sketch map No. 14 above.

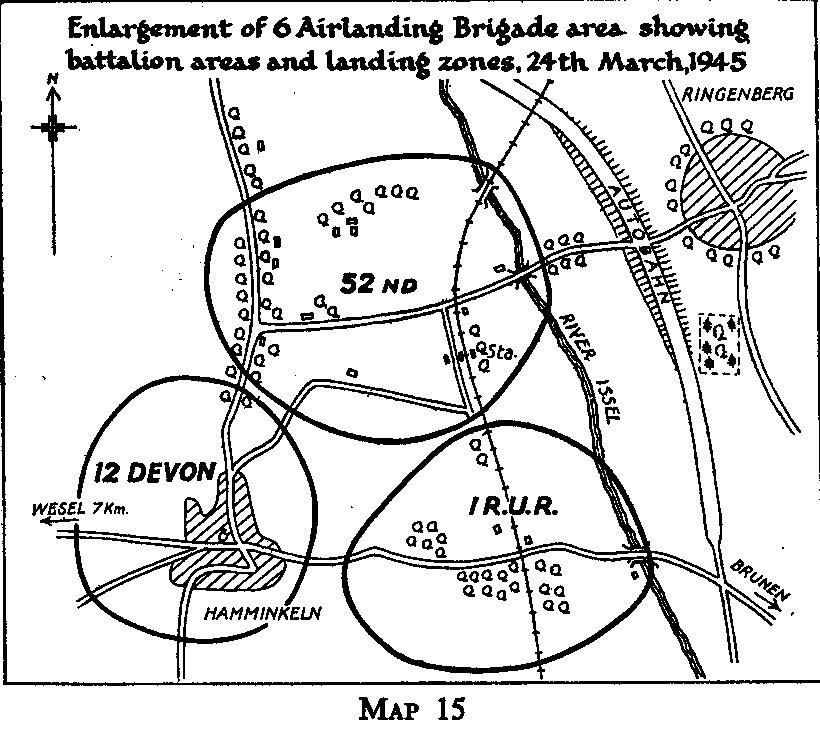

The regiments in the 6th Airlanding Brigade were the 1st Battalion The Royal Ulster Rifles, the 52nd Light Infantry and the 12th Devons. The brigade was commanded by Brigadier Bellamy. Each battalion was allotted observation and forward bombardment officers from the artillery, a troop of engineers and a section of the field ambulance, in support for the operation. The brigade planned to fly in Horsa gliders from airfields in Norfolk. Take-off was to be at dawn, and the approach flight made in a column of loose pairs guarded by some dozen squadrons of fighters along the route. The order of flying was, first, the 52nd, followed by the Royal Ulster Rifles, the 12th Devons and brigade headquarters. The route was southwards over the North Sea, turning east over Brussels, and casting off for landing over Hamminkeln at about 1000 hrs. The aircraft carrying the two parachute brigades would overtake the gliders, passing in a stream below, and dropping the parachutists on their objectives in Diersfordterwald (K52/A14) about fifteen minutes before our gliders landed in the Hamminkeln area. Each battalion and each company of the 6th Airlanding Brigade was to land directly on its objective, the whole attack being a coup de main. The task of the 6th Airlanding Brigade was to capture and hold the road and rail crossing over the River Issel to the east of Hamminkeln, and also the town of Hamminkeln, as a bridgehead until the advancing ground troops had passed through, and to destroy or capture all enemy forces in the area, and prevent enemy reinforcements from moving into the area of Wesel.

Battalion objectives and landing zones are shown in the sketch map.

The Royal Ulster Rifles were to capture the Hamminkeln—Brunen (K52/A24) road bridge over the River Issel;

The 12th Devons the town of Hamminkeln;

and the 52nd the Hamminkeln—Ringenburg (K52/A25) road bridge over the Issel, the railway bridge about two hundred yards to the north of it, Hamminkeln railway station, and the road junction to the west.

It was known that the enemy had a small garrison at Hamminkein and at

Ringenburg who would probably guard the road bridges, and also that there was quite a number of light antiaircraft guns on our landing zone. The enemy would probably try to counter-attack us, and it was possible that columns of reinforcements might be moving through the area as we landed.

Outline Organization of the Battalion.

As a battalion in an airlanding brigade, the 52nd was organized into four rifle companies, each of three platoons with an officer, a serjeant and twenty-eight soldiers, a support company and headquarters company. Each rifle platoon had a Piat (anti-tank bomb projector), three light machine guns, four machine carbines, a wireless, and light metal handcart with bicycle type wheels in which to carry some of its stores. Personal equipment consisted of a smock, a small haversack, entrenching tool, water-bottle, webbing waist-belt and ammunition pouches.

A Horsa glider carried one rifle platoon and its handcart. Rifle company

headquarters included a jeep 5-cwt car and a trailer, and it travelled in one

glider. Support Company was the biggest company. It had two anti-tank-gun platoons, each equipped with four 6-pounder guns and six jeeps; three 3-inch mortar platoons, each with four 3-inch trench mortars, five jeeps and trailers; one medium machine-gun platoon equipped with four Vickers medium machine guns, six jeeps and trailers; and a company headquarters of two jeeps and two trailers. A Horsa glider would carry a jeep and 6-pounder and crew of six, or a jeep and loader trailer and similar crew. HO. Company included Regimental headquarters the signal platoon, pioneer platoon, reconnaissance platoon, motor transport platoon, and the quartermaster’s administrative platoon. The reconnaissance platoon in this coinpany had four Vickers machine guns, jeeps, trailers and motorcycles. Of the Regimental organization described above, the administrative platoon, most of the motor transport platoon, a second jeep and trailer for each company, various quarter master-serjeants, clerks and drivers, formed the “sea” and “land tails.” The remainder were squeezed into gliders somehow.

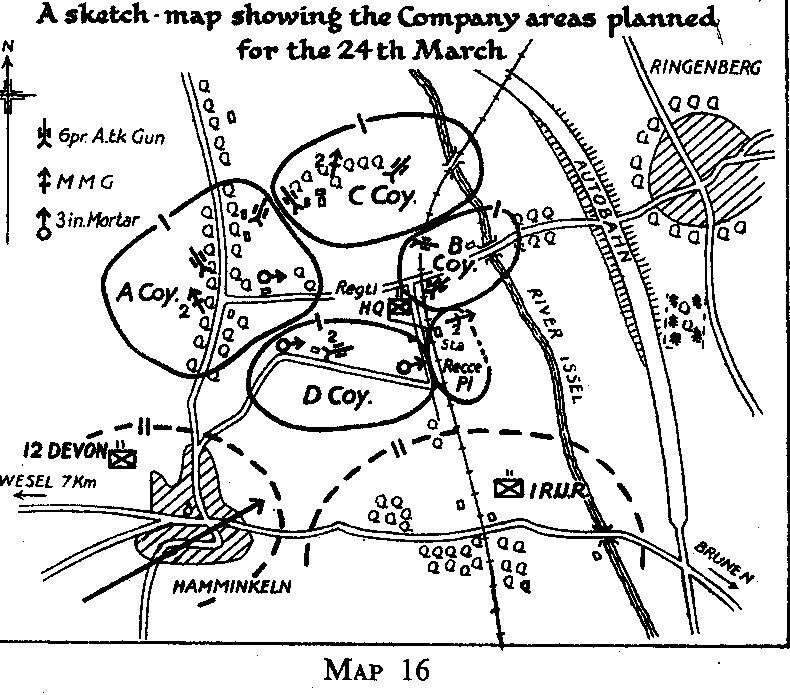

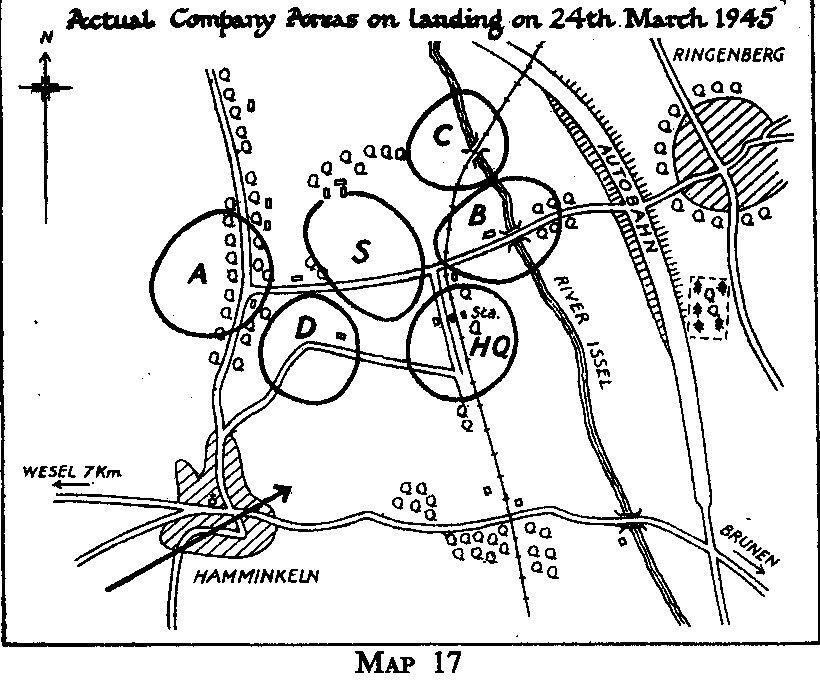

Full details concerning the regiments role in the assault over the Rhine were clearly described to all ranks at the briefing before the commanding officer (Lieutenant-Colonel Darell-Brown, D.S.O.) gave his plan and orders. If the initial crossing by XII Corps progressed successfully the 52nd would take off at 0615 hrs. on the 24th March, using two airfields, Birch and Gosfield. The airfields were about ten miles apart, and the majority of heavier loads of Support Company and Regimental headquarters were to fly from Gosfield. At about 1000 hrs. our gliders would be approaching Hamminkein from the west, and the church there was to be the landmark for casting off from the tugs. Our landing zone should be quite dear, as the broad yellow strip of the unfinished autobahn, and the railway, appeared to show up well on the air photographs. The whole Regiment was to land in one wave, and each company was allotted a landing zone round its objective. Companies ordered to capture the bridges were to land as close as possible to them. The company landing zones are shown in the sketch map No. 16.

EXTRACTS FROM THE COMMANDING OFFICER’S VERBAL ORDERS

(a) INTENTION

The 52nd was to seize and hold the line of the River Issel north-west of Hamminkeln from inclusive the railway station to inclusive the railway bridge over the river to inclusive the Hamminkeln—Ringenburg road

junction.

(b) GROUPING AND TASKS.

(i) Letter C Company, supported by two 6-pounder anti-tank guns and a section of medium guns, was to seize and hold the railway bridge and group of farm buildings to the west of it.

(ii) Letter B Company, supported by two anti-tank guns and a detachment of sappers, was to seize and hold the road bridge over the river. This bridge was to be taken intact if possible and prepared for demolition by us. It was not essential for the bridge to be held intact, but it was only to be blown on orders from the brigade commander.

(iii) Letter A Company, with two anti-tank guns and a section of medium machine guns, was to seize and hold the area of the road junction north of Hamminkeln, to link up with C Cornpany across the north of the Regiment’s position, to link up with the 12th Devons in Hamminkeln,and to establish contact west.wards with troops of the 5th Parachute Brigade.

(iv) Letter D Company, with two anti-tank guns, was to be in a defensive position in reserve in the area of the track westwards from the station to Hamminkeln. It was to be prepared to make immediate local counter-attacks if necessary, and to undertake patrolling. D Company was also to establish a prisoner-of-war cage.

(v) The reconnaissance platoons were to defend the railway station, assisted by any available glider pilots, and to link up with the Royal Ulster Rifles on their right.

(vi) Regimental headquarters and the aid post were to be established in the railway station buildings.

(vii) Direct-fire support was available from our own affiliated battery of the Worcestershire Yeomanry and the 3-inch mortars. In addition, supportin fire could be given by the divisional artillery, artillery already across the Rhine, and medium artillery west of the Rhine.

Communications were available to call for air support.

By the evening of the 23rd the gliders were all loaded and dispersed ready for the morrow. All planning and briefing had been completed, and morale was high. The weather was good, and it looked like being a successful operation. There was a spirit of excitement about, and at dusk lively singing was to be heard throughout the camp. Enforced rest started at 2100 hrs., but it took a long time to get to sleep.

On the 24th March the camp was roused at 0230 hrs. in the darkness of a fine, cold morning. We had a good but hasty breakfast of fried eggs, bacon and beans; and moved off for the airfield at 0400 hrs promptly. All went smoothly on arrival as platoons and detachments left the trucks and made their way into the darkness to find their gliders. By 0530 hrs. everyone was aboard and ready. The tug aircraft started running-up their engines, nippy little tractors towed our heavy, lumbering gliders into a long double queue at the down-wind end of the runway, the long tow-ropes were laid on the runway in neat lines ready to be connected, and our bomber tugs wheeled into lines at right angles to the gliders and to left and right. Finally, mobile canteen car went down the row of gliders dispensing welcome cups of hot tea.

The leading bombers turned into the runway, the tow-rope was connected, a flag was waved to take up the slack, another flag was waved, and with a shattering roar the first combination swept down the runway, throttle wide for the take-off. It was quickly followed by the next in the queue, the next and next, until within a few minutes all were airborne and gliding southwards in the dawn to join the remainder of the brigade. It was 0630 hrs. We loosened our safety belts and settled down for the long flight.

The air was still and placid, and the flight uneventful. Even those most prone to air sickness could scarcely have felt a twinge that morning. We sat listening to the even roar of the slipstream. The sun rose in a clear blue sky, and we were over the sea in long, loose columns of pairs. Now and then the fighter escort was to be seen weaving high above, or scudding past below. As we passed over Brussels the Dakota aircraft of the parachute brigades slowly overtook us, flying in neat, light “Vic” formation. Shortly afterwards one of our gliders broke its tow and circled down to land in a Belgian field.

At about 1000 hrs. we could see that we were approaching the Rhine, a broad, black ribbon below us. We saw the flashes of the guns, the heavy pall of smoke drifting away from Wesel, and the white wake of craft speeding across the river.

Then we saw black puffs in the sky ahead, and realized that we were flying into a barrage of anti-aircraft fire. Several tugs ahead had cast off, turning

southwards with bright orange flames belching from their engines. The battle was on. Seconds later all was pandemonium. We caught a glimpse of Hamminkeln church ahead, but our landing zone was obscured by a thick haze of smoke and dust drifting down from Wesel. Gliders were crashing down, gliders were on fire, the sky was full of air bursts and ribbons of tracer, but our pilots carried on.

They were wonderful. We cast off and slowly circled round looking for the field in which we had to land, and were followed all the way down by flak.

There were four enemy anti-aircraft gun-pits sited near the station, each

having four multiple two- or four-barrelled 20-mm anti-aircraft guns. Some of these were deliberately run down by landing gliders.

During the landing, which took only ten minutes to complete. we lost about half our total strength. The casualties were awful. Gliders circling in through the gloom of the smoke and flak piled into woods, into buildings, collided on the ground, crashed flaming from the sky, and some blew into smithereens as they came in. The quartermaster (Aldworth), with no flying instruction, landed his own glider safely with the pilots dead at the controls. Captain Bousfield, of A Company, landed almost on a German armoured half-track which he immediately commandeered. Despite the chaotic landing, a useful number of gliders landed correctly on the chosen objectives, but it was impossible to unload many of the gliders containing jeeps and heavy supporting weapons until after dark.

Probably Support Company suffered the worst casualties, as all their gliders carried jeeps and a great deal of ammunition. It seems amazing that none of us realized that, whereas a glider loaded with troops can take an enormous amount of punishment, can be raked with anti-aircraft fire and yet continue to fly provided that both pilots are not hit, a glider containing a jeep with full petrol tanks, spare cans and ammunition catches fire and probably blows up from the first unlucky bullet. The gliders were built of wood, paper and glue, and, being covered in “dope,”burnt like celluloid. None of us fully appreciated this danger, nor the fact that the landing zone might be obscured by smoke. We blissfully relied on the fact that the anti-aircraft guns we encountered were going to be knocked out before we arrived. Unfortunately they were not. Probably we should have done better and saved many valuable lives if we had flown in the heavy weapons as a second wave, but it is easy to be wise after the event.

At first the battle was very confused, as are all airborne assaults. In addition to the several private baffles going on round company objectives, ammunition was continually exploding in burning gliders, and it was difficult to distinguish friend from foe. Fortunately most of the German troops manning the antiaircraft guns were of low calibre, and surrendered when they found themselves surrounded and in the midst of the crashing. Over one hundred prisoners were taken, and others escaped to the east. But as the anti-aircraft guns were knocked out, enemy machine guns and mortars opened fire on the landing zone from Ringenburg, and there was a small garrison defending the bridge in the Royal Ulster Rifles’ area. Also three German medium tanks escorted by motor-cyclists, apparently fleeing to the east, drove across the area while landing was still in progress.

Although they did not wait to become engaged, they fired tracer bullets into several wrecked gliders, setting them alight before the casualties aboard them could get clear. The Royal Ulster Rifles “drummed up” one of these tanks before it could escape over their bridge. Despite our very heavy casualties, all objectives were quickly captured and occupied. At 1100 hrs. we got through by wireless to brigade headquarters and reported that the position was captured. By midday firing had ceased, and we consolidated and dug ourselves in.

We were now able to collect our wounded. There were over a hundred, and some were in a very bad way. The two medical officers, Captain S. Smith, our own medical officer, and Captain Prentice, of the field ambulance, did some wonderful work to relieve the wounded, working in the cramped quarters of the station buildings. The wounded were remarkably patient and cheerful. They well knew that there was no chance for them to be evacuated from the battlefield until the ground forces linked up with us; but they hung on.

At about 1300 hrs. American heavy transport planes flew over and dropped supplies for us near Hamminkeln. Unfortunately they appeared to think that we were Germans and shot us up with their machine guns. However, no one was hit, and the incident was soon forgotten.

We learnt from our artillery officers that the airborne divisional artillery had lost most of its guns during its landing; at the same time only four of our twelve 3-inch mortars were in action. However, our artillery forward observation team were able to make contact with the medium artillery west of the Rhine and so we were not entirely without support.

After the initial fighting on landing, the enemy left us in peace for the remaining hours of daylight, though we knew something was brewing behind Ringenburg, and we expected to be counter-attacked at any moment. Nevertheless, we were fortunate to get this opportunity to consolidate and examine the area. To the east, over the River Issel, the village of Ringenburg was completely surrounded by a thick, circular belt of elm trees, and completely hidden.

Between Ringenburg and the river lay the broad curve of the autobahn, which was so steeply banked at this point that enemy tanks could form up behind unseen.

The River Issel was a miserable, narrow stream, and was embanked like a canal about three feet above the level of the fields. The road bridge was a small, hump-backed, brick bridge, and the railway bridge was of a single cantilever span girder construction. The railway itself had been heavily bombed and was blocked by two bombed-out locomotives. In the station stood a train of goods wagons loaded with shells, bombs and aircraft auxiliary petrol tanks. The surrounding country was level, arable land, unhedged except down the roads. But there was quite a number of trees along the roads and tracks, and particularly round the station buildings. The few buildings in the area were brick with tiled roofs.

During the evening our casualties were evacuated to a medical centre established by divisional headquarters farther to the rear. At about this time an enemy post opened fire on Letter C Company at the railway bridge, and at 2000 hrs.

Lieutenant Stone took out a fighting patrol and silenced it, killing two Germans and taking two prisoners. A little later Letter B Company, holding the road bridge, heard tanks approaching from Ringenburg, and medium artillery fire was directed into the area. However, this was not effective, and at about midnight enemy tanks and infantry attacked the bridge. Our anti-tank guns engaged the enemy and scored hits, but the tanks were too heavy and continued to threaten the bridge. The fighting round the bridge in the darkness was very confused. A B Company position on the east of the bridge was overwhelmed, and Lieutenant Clarke led his platoon in a charge to retake it.

However, at 0200 hrs. on the 25th March it seemed unlikely that B Company could keep the enemy from crossing, and the brigade commander ordered the bridge to be blown. This was done at 0230 hrs. when an enemy tank was almost across it. The attack ceased at 0300 hrs., but our medium artillery continued harassing fire.

At 0400 hrs. a small force of enemy infantry started working round the northern side of our position, and managed to infiltrate in the dark between Letter A and Letter C Companies, who were very thin on the ground on that flank.

At 0445 hrs. the enemy force attacked Letter C Company and overran one platoon position in the dark. They captured an anti-tank-gun detachment and SOS fire was called down. The commanding officer ordered Letter A Company to make a counter-attack to stabilize the situation, and at the same time troops of the 12th Devons moved up and took over the road junction held by A Company while the counter-attack was launched. On being counter-attacked the enemy raiders withdrew, and our perimeter was intact again.

At 0530 hrs. enemy tank activity started again between Ringenburg and the river. On two German medium tanks being seen a request was wirelessed to brigade headquarters for an air strike on Ringenburg at dawn.

At 0700 hrs six Typhoon “tankbusting” fighters appeared overhead and gave a brilliant display, diving on Ringenburg from all angles, attacking the tanks there with rockets. They apparently scored several hits, as columns of black, oily smoke rose from the area. However, they were unable to knock out one heavy tank which was in a well-chosen hull-down position covering the blown bridge. This tank sniped us throughout the day, and later in the day killed Captain Moncrieff, who had just taken over command of Support Company.

In our morning situation report to brigade headquarters we were able to state that our position was intact and no enemy were in our area.

This report showed the Regiment’s strength as:

A Company, four officers and fifty-six other ranks;

B Company, two and forty-five;

C Company, four and fifty-two; and

D Company, five and fifty-eight.

We were slightly less than half strength and were getting tired.

The day was fine, sunny and warm and the enemy were not very active. At about 1200 hrs we learnt that the leading troops of ground forces had made touch with the parachute brigades behind us. During the afternoon movement was observed at intervals in buildings to our north and north-west, and in the evening Letter D Company made a raid under cover of artillery and mortar fire to clear these buildings.

At 1900 hrs the commanding officer went to a conference at brigade headquarters, and the relief of the brigade was planned. Shortly after dusk, advanced parties of the 157th Brigade of the 52nd (Lowland) Division arrived to reconnoitre our positions and post guides for the troops who were to relieve us. However, we had still not finished our efforts for the day, and at 2040 hrs Letter A Company mounted a further raid on the building to the north. Although it was successful the raiding party was engaged by several parties of enemy, and on one occasion by enemy who fired from behind a group of civilians bearing a white flag. Lieutenant Gunter, who led the raid, was wounded in the ensuing shooting.

At about midnight troops of the Cameronians started moving in to relieve us. They were rather noisy and the enemy shelled the area throughout the relief. However, few casualties were sustained, and the 52nd marched out dog-tired. By 0200 hrs. the Regiment concentrated in some farm buildings on the western outskirts of Hamminkeln where we all lay down and snatched a few hours’ sleep in preparation for the advance planned to begin the next day. 1

The 6th Airborne Division was commanded by Major-General Bols, and consisted of the 3rd Parachute Brigade, 5th Parachute Brigade and 6th Airlanding Brigade. These were supported by an airborne armoured reconnaissance regiment, the 53rd Airborne Light Regiment, Worcestershire Yeomanry, R.A., engineers and other airborne divisional troops. In addition the division would land within range of supporting fire from XII Corp medium artillery. Each of the brigades consisted of three battalions.

The whole of XVIII Airborne Corps was to be landed at the same time direct on to their objectives. The sectors allotted to the three brigades of the 6th Airborne Division and to the 17th U.S. Airborne Division are shown in the sketch map No. 14 above.

The regiments in the 6th Airlanding Brigade were the 1st Battalion The Royal Ulster Rifles, the 52nd Light Infantry and the 12th Devons. The brigade was commanded by Brigadier Bellamy. Each battalion was allotted observation and forward bombardment officers from the artillery, a troop of engineers and a section of the field ambulance, in support for the operation. The brigade planned to fly in Horsa gliders from airfields in Norfolk. Take-off was to be at dawn, and the approach flight made in a column of loose pairs guarded by some dozen squadrons of fighters along the route. The order of flying was, first, the 52nd, followed by the Royal Ulster Rifles, the 12th Devons and brigade headquarters. The route was southwards over the North Sea, turning east over Brussels, and casting off for landing over Hamminkeln at about 1000 hrs. The aircraft carrying the two parachute brigades would overtake the gliders, passing in a stream below, and dropping the parachutists on their objectives in Diersfordterwald (K52/A14) about fifteen minutes before our gliders landed in the Hamminkeln area. Each battalion and each company of the 6th Airlanding Brigade was to land directly on its objective, the whole attack being a coup de main. The task of the 6th Airlanding Brigade was to capture and hold the road and rail crossing over the River Issel to the east of Hamminkeln, and also the town of Hamminkeln, as a bridgehead until the advancing ground troops had passed through, and to destroy or capture all enemy forces in the area, and prevent enemy reinforcements from moving into the area of Wesel.

Battalion objectives and landing zones are shown in the sketch map.

The Royal Ulster Rifles were to capture the Hamminkeln—Brunen (K52/A24) road bridge over the River Issel;

The 12th Devons the town of Hamminkeln;

and the 52nd the Hamminkeln—Ringenburg (K52/A25) road bridge over the Issel, the railway bridge about two hundred yards to the north of it, Hamminkeln railway station, and the road junction to the west.

It was known that the enemy had a small garrison at Hamminkein and at

Ringenburg who would probably guard the road bridges, and also that there was quite a number of light antiaircraft guns on our landing zone. The enemy would probably try to counter-attack us, and it was possible that columns of reinforcements might be moving through the area as we landed.

Outline Organization of the Battalion.

As a battalion in an airlanding brigade, the 52nd was organized into four rifle companies, each of three platoons with an officer, a serjeant and twenty-eight soldiers, a support company and headquarters company. Each rifle platoon had a Piat (anti-tank bomb projector), three light machine guns, four machine carbines, a wireless, and light metal handcart with bicycle type wheels in which to carry some of its stores. Personal equipment consisted of a smock, a small haversack, entrenching tool, water-bottle, webbing waist-belt and ammunition pouches.

A Horsa glider carried one rifle platoon and its handcart. Rifle company

headquarters included a jeep 5-cwt car and a trailer, and it travelled in one

glider. Support Company was the biggest company. It had two anti-tank-gun platoons, each equipped with four 6-pounder guns and six jeeps; three 3-inch mortar platoons, each with four 3-inch trench mortars, five jeeps and trailers; one medium machine-gun platoon equipped with four Vickers medium machine guns, six jeeps and trailers; and a company headquarters of two jeeps and two trailers. A Horsa glider would carry a jeep and 6-pounder and crew of six, or a jeep and loader trailer and similar crew. HO. Company included Regimental headquarters the signal platoon, pioneer platoon, reconnaissance platoon, motor transport platoon, and the quartermaster’s administrative platoon. The reconnaissance platoon in this coinpany had four Vickers machine guns, jeeps, trailers and motorcycles. Of the Regimental organization described above, the administrative platoon, most of the motor transport platoon, a second jeep and trailer for each company, various quarter master-serjeants, clerks and drivers, formed the “sea” and “land tails.” The remainder were squeezed into gliders somehow.

Full details concerning the regiments role in the assault over the Rhine were clearly described to all ranks at the briefing before the commanding officer (Lieutenant-Colonel Darell-Brown, D.S.O.) gave his plan and orders. If the initial crossing by XII Corps progressed successfully the 52nd would take off at 0615 hrs. on the 24th March, using two airfields, Birch and Gosfield. The airfields were about ten miles apart, and the majority of heavier loads of Support Company and Regimental headquarters were to fly from Gosfield. At about 1000 hrs. our gliders would be approaching Hamminkein from the west, and the church there was to be the landmark for casting off from the tugs. Our landing zone should be quite dear, as the broad yellow strip of the unfinished autobahn, and the railway, appeared to show up well on the air photographs. The whole Regiment was to land in one wave, and each company was allotted a landing zone round its objective. Companies ordered to capture the bridges were to land as close as possible to them. The company landing zones are shown in the sketch map No. 16.

EXTRACTS FROM THE COMMANDING OFFICER’S VERBAL ORDERS

(a) INTENTION

The 52nd was to seize and hold the line of the River Issel north-west of Hamminkeln from inclusive the railway station to inclusive the railway bridge over the river to inclusive the Hamminkeln—Ringenburg road

junction.

(b) GROUPING AND TASKS.

(i) Letter C Company, supported by two 6-pounder anti-tank guns and a section of medium guns, was to seize and hold the railway bridge and group of farm buildings to the west of it.

(ii) Letter B Company, supported by two anti-tank guns and a detachment of sappers, was to seize and hold the road bridge over the river. This bridge was to be taken intact if possible and prepared for demolition by us. It was not essential for the bridge to be held intact, but it was only to be blown on orders from the brigade commander.

(iii) Letter A Company, with two anti-tank guns and a section of medium machine guns, was to seize and hold the area of the road junction north of Hamminkeln, to link up with C Cornpany across the north of the Regiment’s position, to link up with the 12th Devons in Hamminkeln,and to establish contact west.wards with troops of the 5th Parachute Brigade.

(iv) Letter D Company, with two anti-tank guns, was to be in a defensive position in reserve in the area of the track westwards from the station to Hamminkeln. It was to be prepared to make immediate local counter-attacks if necessary, and to undertake patrolling. D Company was also to establish a prisoner-of-war cage.

(v) The reconnaissance platoons were to defend the railway station, assisted by any available glider pilots, and to link up with the Royal Ulster Rifles on their right.

(vi) Regimental headquarters and the aid post were to be established in the railway station buildings.

(vii) Direct-fire support was available from our own affiliated battery of the Worcestershire Yeomanry and the 3-inch mortars. In addition, supportin fire could be given by the divisional artillery, artillery already across the Rhine, and medium artillery west of the Rhine.

Communications were available to call for air support.

By the evening of the 23rd the gliders were all loaded and dispersed ready for the morrow. All planning and briefing had been completed, and morale was high. The weather was good, and it looked like being a successful operation. There was a spirit of excitement about, and at dusk lively singing was to be heard throughout the camp. Enforced rest started at 2100 hrs., but it took a long time to get to sleep.

On the 24th March the camp was roused at 0230 hrs. in the darkness of a fine, cold morning. We had a good but hasty breakfast of fried eggs, bacon and beans; and moved off for the airfield at 0400 hrs promptly. All went smoothly on arrival as platoons and detachments left the trucks and made their way into the darkness to find their gliders. By 0530 hrs. everyone was aboard and ready. The tug aircraft started running-up their engines, nippy little tractors towed our heavy, lumbering gliders into a long double queue at the down-wind end of the runway, the long tow-ropes were laid on the runway in neat lines ready to be connected, and our bomber tugs wheeled into lines at right angles to the gliders and to left and right. Finally, mobile canteen car went down the row of gliders dispensing welcome cups of hot tea.

The leading bombers turned into the runway, the tow-rope was connected, a flag was waved to take up the slack, another flag was waved, and with a shattering roar the first combination swept down the runway, throttle wide for the take-off. It was quickly followed by the next in the queue, the next and next, until within a few minutes all were airborne and gliding southwards in the dawn to join the remainder of the brigade. It was 0630 hrs. We loosened our safety belts and settled down for the long flight.

The air was still and placid, and the flight uneventful. Even those most prone to air sickness could scarcely have felt a twinge that morning. We sat listening to the even roar of the slipstream. The sun rose in a clear blue sky, and we were over the sea in long, loose columns of pairs. Now and then the fighter escort was to be seen weaving high above, or scudding past below. As we passed over Brussels the Dakota aircraft of the parachute brigades slowly overtook us, flying in neat, light “Vic” formation. Shortly afterwards one of our gliders broke its tow and circled down to land in a Belgian field.

At about 1000 hrs. we could see that we were approaching the Rhine, a broad, black ribbon below us. We saw the flashes of the guns, the heavy pall of smoke drifting away from Wesel, and the white wake of craft speeding across the river.

Then we saw black puffs in the sky ahead, and realized that we were flying into a barrage of anti-aircraft fire. Several tugs ahead had cast off, turning

southwards with bright orange flames belching from their engines. The battle was on. Seconds later all was pandemonium. We caught a glimpse of Hamminkeln church ahead, but our landing zone was obscured by a thick haze of smoke and dust drifting down from Wesel. Gliders were crashing down, gliders were on fire, the sky was full of air bursts and ribbons of tracer, but our pilots carried on.

They were wonderful. We cast off and slowly circled round looking for the field in which we had to land, and were followed all the way down by flak.

There were four enemy anti-aircraft gun-pits sited near the station, each

having four multiple two- or four-barrelled 20-mm anti-aircraft guns. Some of these were deliberately run down by landing gliders.

During the landing, which took only ten minutes to complete. we lost about half our total strength. The casualties were awful. Gliders circling in through the gloom of the smoke and flak piled into woods, into buildings, collided on the ground, crashed flaming from the sky, and some blew into smithereens as they came in. The quartermaster (Aldworth), with no flying instruction, landed his own glider safely with the pilots dead at the controls. Captain Bousfield, of A Company, landed almost on a German armoured half-track which he immediately commandeered. Despite the chaotic landing, a useful number of gliders landed correctly on the chosen objectives, but it was impossible to unload many of the gliders containing jeeps and heavy supporting weapons until after dark.

Probably Support Company suffered the worst casualties, as all their gliders carried jeeps and a great deal of ammunition. It seems amazing that none of us realized that, whereas a glider loaded with troops can take an enormous amount of punishment, can be raked with anti-aircraft fire and yet continue to fly provided that both pilots are not hit, a glider containing a jeep with full petrol tanks, spare cans and ammunition catches fire and probably blows up from the first unlucky bullet. The gliders were built of wood, paper and glue, and, being covered in “dope,”burnt like celluloid. None of us fully appreciated this danger, nor the fact that the landing zone might be obscured by smoke. We blissfully relied on the fact that the anti-aircraft guns we encountered were going to be knocked out before we arrived. Unfortunately they were not. Probably we should have done better and saved many valuable lives if we had flown in the heavy weapons as a second wave, but it is easy to be wise after the event.

At first the battle was very confused, as are all airborne assaults. In addition to the several private baffles going on round company objectives, ammunition was continually exploding in burning gliders, and it was difficult to distinguish friend from foe. Fortunately most of the German troops manning the antiaircraft guns were of low calibre, and surrendered when they found themselves surrounded and in the midst of the crashing. Over one hundred prisoners were taken, and others escaped to the east. But as the anti-aircraft guns were knocked out, enemy machine guns and mortars opened fire on the landing zone from Ringenburg, and there was a small garrison defending the bridge in the Royal Ulster Rifles’ area. Also three German medium tanks escorted by motor-cyclists, apparently fleeing to the east, drove across the area while landing was still in progress.

Although they did not wait to become engaged, they fired tracer bullets into several wrecked gliders, setting them alight before the casualties aboard them could get clear. The Royal Ulster Rifles “drummed up” one of these tanks before it could escape over their bridge. Despite our very heavy casualties, all objectives were quickly captured and occupied. At 1100 hrs. we got through by wireless to brigade headquarters and reported that the position was captured. By midday firing had ceased, and we consolidated and dug ourselves in.

We were now able to collect our wounded. There were over a hundred, and some were in a very bad way. The two medical officers, Captain S. Smith, our own medical officer, and Captain Prentice, of the field ambulance, did some wonderful work to relieve the wounded, working in the cramped quarters of the station buildings. The wounded were remarkably patient and cheerful. They well knew that there was no chance for them to be evacuated from the battlefield until the ground forces linked up with us; but they hung on.

At about 1300 hrs. American heavy transport planes flew over and dropped supplies for us near Hamminkeln. Unfortunately they appeared to think that we were Germans and shot us up with their machine guns. However, no one was hit, and the incident was soon forgotten.

We learnt from our artillery officers that the airborne divisional artillery had lost most of its guns during its landing; at the same time only four of our twelve 3-inch mortars were in action. However, our artillery forward observation team were able to make contact with the medium artillery west of the Rhine and so we were not entirely without support.

After the initial fighting on landing, the enemy left us in peace for the remaining hours of daylight, though we knew something was brewing behind Ringenburg, and we expected to be counter-attacked at any moment. Nevertheless, we were fortunate to get this opportunity to consolidate and examine the area. To the east, over the River Issel, the village of Ringenburg was completely surrounded by a thick, circular belt of elm trees, and completely hidden.

Between Ringenburg and the river lay the broad curve of the autobahn, which was so steeply banked at this point that enemy tanks could form up behind unseen.

The River Issel was a miserable, narrow stream, and was embanked like a canal about three feet above the level of the fields. The road bridge was a small, hump-backed, brick bridge, and the railway bridge was of a single cantilever span girder construction. The railway itself had been heavily bombed and was blocked by two bombed-out locomotives. In the station stood a train of goods wagons loaded with shells, bombs and aircraft auxiliary petrol tanks. The surrounding country was level, arable land, unhedged except down the roads. But there was quite a number of trees along the roads and tracks, and particularly round the station buildings. The few buildings in the area were brick with tiled roofs.

During the evening our casualties were evacuated to a medical centre established by divisional headquarters farther to the rear. At about this time an enemy post opened fire on Letter C Company at the railway bridge, and at 2000 hrs.

Lieutenant Stone took out a fighting patrol and silenced it, killing two Germans and taking two prisoners. A little later Letter B Company, holding the road bridge, heard tanks approaching from Ringenburg, and medium artillery fire was directed into the area. However, this was not effective, and at about midnight enemy tanks and infantry attacked the bridge. Our anti-tank guns engaged the enemy and scored hits, but the tanks were too heavy and continued to threaten the bridge. The fighting round the bridge in the darkness was very confused. A B Company position on the east of the bridge was overwhelmed, and Lieutenant Clarke led his platoon in a charge to retake it.

However, at 0200 hrs. on the 25th March it seemed unlikely that B Company could keep the enemy from crossing, and the brigade commander ordered the bridge to be blown. This was done at 0230 hrs. when an enemy tank was almost across it. The attack ceased at 0300 hrs., but our medium artillery continued harassing fire.

At 0400 hrs. a small force of enemy infantry started working round the northern side of our position, and managed to infiltrate in the dark between Letter A and Letter C Companies, who were very thin on the ground on that flank.

At 0445 hrs. the enemy force attacked Letter C Company and overran one platoon position in the dark. They captured an anti-tank-gun detachment and SOS fire was called down. The commanding officer ordered Letter A Company to make a counter-attack to stabilize the situation, and at the same time troops of the 12th Devons moved up and took over the road junction held by A Company while the counter-attack was launched. On being counter-attacked the enemy raiders withdrew, and our perimeter was intact again.

At 0530 hrs. enemy tank activity started again between Ringenburg and the river. On two German medium tanks being seen a request was wirelessed to brigade headquarters for an air strike on Ringenburg at dawn.

At 0700 hrs six Typhoon “tankbusting” fighters appeared overhead and gave a brilliant display, diving on Ringenburg from all angles, attacking the tanks there with rockets. They apparently scored several hits, as columns of black, oily smoke rose from the area. However, they were unable to knock out one heavy tank which was in a well-chosen hull-down position covering the blown bridge. This tank sniped us throughout the day, and later in the day killed Captain Moncrieff, who had just taken over command of Support Company.

In our morning situation report to brigade headquarters we were able to state that our position was intact and no enemy were in our area.

This report showed the Regiment’s strength as:

A Company, four officers and fifty-six other ranks;

B Company, two and forty-five;

C Company, four and fifty-two; and

D Company, five and fifty-eight.

We were slightly less than half strength and were getting tired.

The day was fine, sunny and warm and the enemy were not very active. At about 1200 hrs we learnt that the leading troops of ground forces had made touch with the parachute brigades behind us. During the afternoon movement was observed at intervals in buildings to our north and north-west, and in the evening Letter D Company made a raid under cover of artillery and mortar fire to clear these buildings.

At 1900 hrs the commanding officer went to a conference at brigade headquarters, and the relief of the brigade was planned. Shortly after dusk, advanced parties of the 157th Brigade of the 52nd (Lowland) Division arrived to reconnoitre our positions and post guides for the troops who were to relieve us. However, we had still not finished our efforts for the day, and at 2040 hrs Letter A Company mounted a further raid on the building to the north. Although it was successful the raiding party was engaged by several parties of enemy, and on one occasion by enemy who fired from behind a group of civilians bearing a white flag. Lieutenant Gunter, who led the raid, was wounded in the ensuing shooting.

At about midnight troops of the Cameronians started moving in to relieve us. They were rather noisy and the enemy shelled the area throughout the relief. However, few casualties were sustained, and the 52nd marched out dog-tired. By 0200 hrs. the Regiment concentrated in some farm buildings on the western outskirts of Hamminkeln where we all lay down and snatched a few hours’ sleep in preparation for the advance planned to begin the next day. 1

1. The Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry Chronicle, Vol 4: June 1944 - December 1945 Pages 299 - 314

Proudly powered by Weebly