- HOME

- SOLDIER RESEARCH

- WOLVERTONS AMATEUR MILITARY TRADITION

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE RIFLE VOLUNTEERS 1859-1908

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BATTALION 1908-1947

- The Bucks Battalion A Brief History

- REGIMENTAL MARCH

-

1ST BUCKS 1914-1919

>

- 1914-15 1/1ST BUCKS MOBILISATION

- 1915 1/1ST BUCKS PLOEGSTEERT

- 1915-16 1/1st BUCKS HEBUTERNE

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS SOMME JULY 1916

- 1916 1/1st BUCKS POZIERES WAR DIARY 17-25 JULY

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS SOMME AUGUST 1916

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS LE SARS TO CAPPY

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS THE GERMAN RETIREMENT

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS TOMBOIS FARM

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS THE HINDENBURG LINE

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS 3RD BATTLE OF YPRES

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES 16th AUGUST

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES WAR DIARY 15-17 JULY

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS 3RD BATTLE OF YPRES - VIMY

- 1917-18 1/1ST BUCKS ITALY

-

2ND BUCKS 1914-1918

>

- 1914-1916 2ND BUCKS FORMATION & TRAINING

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS ARRIVAL IN FRANCE

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS FROMELLES

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS REORGANISATION

- 1916-1917 2/1st BUCKS THE SOMME

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS THE GERMAN RETIREMENT

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS ST QUENTIN APRIL TO AUGUST 1917

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS ARRAS & CAMBRAI

- 1918 2/1st BUCKS ST QUENTIN TO DISBANDMENT

-

1ST BUCKS 1939-1945

>

- 1939-1940 1BUCKS MOBILISATION & NEWBURY

- 1940 1BUCKS FRANCE & BELGIUM

- 1940 1BUCKS HAZEBROUCK

- HAZEBROUCK BATTLEFIELD VISIT

- 1940-1942 1BUCKS

- 1943-1944 1BUCKS PREPARING FOR D DAY

- COMPOSITION & ROLE OF BEACH GROUP

- BROAD OUTLINE OF OPERATION OVERLORD

- 1944 1ST BUCKS NORMANDY D DAY

- 1944 1BUCKS 1944 NORMANDY TO BRUSSELS (LOC)

- Sword Beach Gallery

- 1945 1BUCKS 1945 FEBRUARY-JUNE T FORCE 1st (CDN) ARMY

- 1945 1BUCKS 1945 FEBRUARY-JUNE T FORCE 2ND BRITISH ARMY

- 1945 1BUCKS JUNE 1945 TO AUGUST 1946

- BUCKS BATTALION BADGES

- BUCKS BATTALION SHOULDER TITLES 1908-1946

- 1939-1945 BUCKS BATTALION DRESS >

- ROYAL BUCKS KINGS OWN MILITIA

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE'S LINE REGIMENTS

- ROYAL GREEN JACKETS

- OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1965

- OXF & BUCKS LI INSIGNIA >

- REGIMENTAL CUSTOMS & TRADITIONS >

- REGIMENTAL COLLECT AND PRAYER

- OXF & BUCKS LI REGIMENTAL MARCHES

- REGIMENTAL DRILL >

-

REGIMENTAL DRESS

>

- REGIMENTAL UNIFORM 1741-1896

- REGIMENTAL UNIFORM 1741-1914

- 1894 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1897 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1900 DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1931 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1939-1945 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1950 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1960 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS (TA)

- 1960 REGIMENTAL MESS DRESS

- 1963 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1958-1969 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- HEADDRESS >

- REGIMENTAL CREST

- BATTLE HONOURS

- REGIMENTAL COLOURS >

- BRIEF HISTORY

- REGIMENTAL CHAPEL, OXFORD >

-

THE GREAT WAR 1914-1918

>

- REGIMENTAL BATTLE HONOURS 1914-1919

- OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY INTRODUCTION

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY

- 1/4 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 2/4 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 1/1 BUCKS BATTALION 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 2/1 BUCKS BATTALION 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 5 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 6 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 7 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 8 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 1st GREEN JACKETS (43rd & 52nd) 1958-1965

- 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND) 1958-1965

- 1959 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1959 REGIMENTAL MARCH IN OXFORD

- 1959 DEMONSTRATION BATTALION

- 1960 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1961 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1961 THE LONGEST DAY

- 1962 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1963 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1963 CONVERSION TO “RIFLE” REGIMENT

- 1964 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1965 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1965 FORMATION OF ROYAL GREEN JACKETS

- REGULAR BATTALIONS 1741-1958

-

1st BATTALION (43rd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

-

43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1914

>

- 43rd REGIMENT 1741-1802

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1803-1805

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1806-1809

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1809-1810

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1810-1812

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1812-1814

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1814-1818

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1818-1854

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1854-1863

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1863-1865

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1865-1897

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1899-1902

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1902-1914

-

1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919

>

-

1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1920-1939

>

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1920

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1921

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1922

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1923

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1924

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1925

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1926

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1927

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1928

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1929

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1930

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1931

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1932

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1933

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1934

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1935

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1936

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1937

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1938

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1939

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945 >

-

1 OXF & BUCKS 1946-1958

>

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1946

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1947

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1948

- 1948 FREEDOM PARADES

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1949

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1950

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1951

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1952

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1953

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1954

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1955

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1956

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1957

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1958

-

43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1914

>

-

2nd BATTALION (52nd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

- 52nd LIGHT INFANTRY 1755-1881 >

- 2 OXF LI 1881-1907

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1908-1914

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919

>

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919-1939

>

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1920

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1921

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1922

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1923

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1924

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1925

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1926

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1927

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1928

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1929

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1930

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1931

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1932

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1933

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1934

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1935

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1936

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1937

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1938

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1939

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945

>

- 1939-1941

- 1941-1943 AIRBORNE INFANTRY

- 1944 PREPARATION FOR D DAY

- 1944 PEGASUS BRIDGE-COUP DE MAIN

- Pegasus Bridge Gallery

- Horsa Bridge Gallery

- COUP DE MAIN NOMINAL ROLL

- MAJOR HOWARDS ORDERS

- 1944 JUNE 6

- D DAY ORDERS

- 1944 JUNE 7-13 ESCOVILLE & HEROUVILETTE

- Escoville & Herouvillette Gallery

- 1944 JUNE 13-AUGUST 16 HOLDING THE BRIDGEHEAD

- 1944 AUGUST 17-31 "PADDLE" TO THE SEINE

- "Paddle To The Seine" Gallery

- 1944 SEPTEMBER ARNHEM

- OPERATION PEGASUS 1

- 1944/45 ARDENNES

- 1945 RHINE CROSSING

- OPERATION VARSITY - ORDERS

- OPERATION VARSITY BATTLEFIELD VISIT

- 1945 MARCH-JUNE

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI DRESS 1940-1945 >

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1946-1947 >

-

1st BATTALION (43rd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

- MILITIA BATTALIONS

- TERRITORIAL BATTALIONS

- WAR RAISED/SERVICE BATTALIONS 1914-18 & 1939-45

-

5th, 6th, 7th & 8th (SERVICE) 1914-1918

>

-

6th & 7th Bns OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945

>

- 6th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI 1940-1945 >

-

7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI 1940-1945

>

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1940-JULY 1942

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JULY 1942 – JUNE 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JULY 1943–OCTOBER 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI OCTOBER 1943–DECEMBER 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI DECEMBER 1943-JUNE 1944

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JANUARY 1944-JUNE 1944

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1944–JANUARY 1945

-

5th, 6th, 7th & 8th (SERVICE) 1914-1918

>

- "IN MY OWN WORDS"

- CREDITS

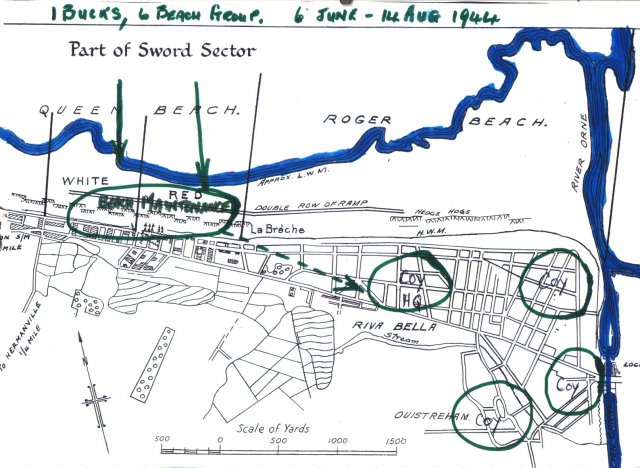

FIRST BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BATTALION

NORMANDY JUNE-AUGUST 1944

BASED ON EXTRACTS FROM THE REGIMENTAL WAR CHRONICLES OF THE OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY VOL4 1944-1945 1

1st-5th June

The long move to marshalling camps was made in troop carriers provided by Movement Control. Eventually all craft parties and transport reached their appropriate camps, where they remained under the orders of Movement Control until either landing overseas or being returned to Petworth camps in the event of a lengthy postponement.

Troops of the beach group were sent to a chain of camps between Waterlooville and Wickham to the north of Portsmouth. Every opportunity was given for rest and the troops were issued with twenty-four-hour packs, vomit bags and a number of other articles needed on the voyage and after landing.

On the 3rd June the bush telegraph reported that embarkation of the assault troops had started, and that “second-tide” troops would embark the following day. But the skies had clouded, and the wind had begun ominously to rise. On the evening of the 3rd the loudspeakers summoned craft-party commanders, and orders were issued for an early move the following morning.

In the early hours of Sunday 4th June, the supreme commander again met his weather experts unknown to the waiting troops, many of whom had already embarked and many more were still sleeping in the marshalling camps. General Eisenhower’s momentous decision set the wires tingling over Southern England. D Day would be he 6th June, 1944. And in the marshalling camps the machine ground to a standstill. There would be a twenty-four-hour postponement. During that day the wind distinctly moderated, though it still blew with some force, and horrid visions of the debacle of Exercise“Grab” were remembered. But there was to be no further postponement, and early on the morning of the 5th June craft parties learned from camp loudspeakers that the day for embarkation had arrived. Once again, as so often before, unwieldy hand-carts were hoisted on to troop carriers; a swift run down the road to Portsmouth; a cup of tea at a transit centre on Southsea front; and then a short march to what was left of Southsea Pier, where craft were awaiting us. As the craft parties, pulling their handcarts, approached the sea front General Eisenhower and his deputy, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder, drove up and wished us God-speed.

They both spent some time chatting to the men and appeared as cheerful as ever.

Apart from first-tide details, which included the Battalion anti-tank platoon (Captain N. L. Smith) in landing craft, tank, and the group reconnaissance party under Major Boehm in landing ship, infantry, the bulk of the marching troops of the beach group was due to embark in ten landing craft, infantry (large). These were long, narrow craft, carrying two hundred men apiece, fitted each with a pair of ramps that let down

on either side of the bow. With their lack of beam and shallow draught they rolled unpleasantly in a seaway, but the draught never seemed sufficiently shallow to give the troops aboard anything but the wettest of wet landings. The greater part of the group’s miscellaneous vehicles with their crews was shipped in considerably greater comfort in landing ships, tank, on to which they embarked from the hards in Gosport.

A staging had been erected on tubular scaffolding close to South Parade and the embarkation of men, handcarts and rations for the voyage proceeded without incident. As each landing craft, infantry, received its complement it set out to take up its station in the convoy.

The Solent presented an unforgettable sight. It was crowded with shipping. Every type of ship was there, from battleships to small assault craft, great ocean liners to rocket craft. It took a quarter-of-an-hour’s steaming to find our place in this convoy in Ryde Roads and there we anchored.

Although we had embarked it was by no means certain that we should sail. Even in the sheltered waters of the Solent the sea was choppy and as the day wore on the chances of sailing appeared to be growing less. But just before dark ships were seen to be moving, only a few at first, and then the bombardment squadron steamed past. Large liners carrying the assaulting infantry followed. The show was on. As dusk was falling a continual stream of shipping was to be seen moving out in long lines past the

Isle of Wight, making for “Piccadilly,” the rendezvous to the south-east of the island, and the open sea. All ranks turned in to enjoy what might be their last night’s unbroken sleep for some time to come.

6th June (D Day)

The second-tide convoy sailed at 0700 hrs. (H hour was at 0725 hrs.) and when we awoke we were at sea and in bright sunshine. The landing craft, infantry, were in line ahead, with the landing ships, tank, also in line ahead to port, and landing craft, tanks, towing anti-aircraft balloons on either quarter. Escorting warships could be seen farther out and the south coast of England was slipping past.

There was a heavy swell running and the shallow-draught landing craft, infantry, rolled and pitched. Those on board them envied the slow and majestic rolling of the landing ships, tank. A good breakfast was made, however, while the wireless informed us that an invasion force had landed on the coast of France. Soon afterwards, captains of craft received the signal to distribute maps, and these, showing for the first time the correct Normandy names, were distributed to those nominated—mostly

officers, and N.C.Os. down to serjeants. Messages from General Eisenhower and General Montgomery were read to the troops.

The coast of England faded away as the convoy turned south, and soon after lunch we entered the swept and buoyed channel leading to the beaches.

A message was signalled to all craft from the beach group commander stating that the assault was proceeding satisfactorily against opposition lighter than had been expected, and that No. 5 Beach Group had completed two exits from the beach.

Apart from returning craft, the first sign of action was the inspiring sight of H.M.S's. Rodney and Warspite lying apparently at anchor off our port quarter engaging the enemy batteries at Le Havre. Large clouds of white smoke billowed out from their sides as they fired broadside after broadside, and the shells could be seen clearly bursting on the hills above the town.

At 1900 hrs. the convoy reached a position approximately one mile off the Normandy coast opposite La Breche, and received a signal from the shore to anchor.

As the battalion approached the Normandy coast first impressions were of a flat

coastline with groups of houses dotted along its shore. On the eastern end the

lighthouse could be seen that marked the entrance to the Caen Canal and Ouistreham church, to the west the woods of Hermanville-sur Mer were recognised from the maps and aerial photographs.

The beach appeared to be deserted apart from bulldozers and small groups of men

constructing the beach lanes.

There was no sign of the balloons or windsocks used to mark the beach exits in training although some beach limit signs had been erected. Clouds of smoke from some of the burning sea front houses drifted inland and across the beach.

The beach was not under fire from the heavy guns at Le Havre so it looked as though plans B or C would not be used. The anchorage was crowded with craft of all sizes.

The Landing Craft Infantry (LCI) carrying the battalion lay at anchor for some thirty minutes before they were signalled to run in to the beach. Unfortunately some of the LCIs landed too far to the west of the beach and grounded in water that was too deep for disembarkation others lost their ramps as they had been lowered into the sea to soon throwing men into the sea. Those LCIs that had beached in deep water refloated and made another run in and the disembarkation began. But again they had beached in deep water six feet in places it was not a dry landing for many of the battalion.

As the battalion struggled ashore through the surf the Luftwaffe made an appearance and flew down the beach dropping a small bomb but was chased off by intense anti aircraft fire.

NORMANDY JUNE-AUGUST 1944

BASED ON EXTRACTS FROM THE REGIMENTAL WAR CHRONICLES OF THE OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY VOL4 1944-1945 1

1st-5th June

The long move to marshalling camps was made in troop carriers provided by Movement Control. Eventually all craft parties and transport reached their appropriate camps, where they remained under the orders of Movement Control until either landing overseas or being returned to Petworth camps in the event of a lengthy postponement.

Troops of the beach group were sent to a chain of camps between Waterlooville and Wickham to the north of Portsmouth. Every opportunity was given for rest and the troops were issued with twenty-four-hour packs, vomit bags and a number of other articles needed on the voyage and after landing.

On the 3rd June the bush telegraph reported that embarkation of the assault troops had started, and that “second-tide” troops would embark the following day. But the skies had clouded, and the wind had begun ominously to rise. On the evening of the 3rd the loudspeakers summoned craft-party commanders, and orders were issued for an early move the following morning.

In the early hours of Sunday 4th June, the supreme commander again met his weather experts unknown to the waiting troops, many of whom had already embarked and many more were still sleeping in the marshalling camps. General Eisenhower’s momentous decision set the wires tingling over Southern England. D Day would be he 6th June, 1944. And in the marshalling camps the machine ground to a standstill. There would be a twenty-four-hour postponement. During that day the wind distinctly moderated, though it still blew with some force, and horrid visions of the debacle of Exercise“Grab” were remembered. But there was to be no further postponement, and early on the morning of the 5th June craft parties learned from camp loudspeakers that the day for embarkation had arrived. Once again, as so often before, unwieldy hand-carts were hoisted on to troop carriers; a swift run down the road to Portsmouth; a cup of tea at a transit centre on Southsea front; and then a short march to what was left of Southsea Pier, where craft were awaiting us. As the craft parties, pulling their handcarts, approached the sea front General Eisenhower and his deputy, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder, drove up and wished us God-speed.

They both spent some time chatting to the men and appeared as cheerful as ever.

Apart from first-tide details, which included the Battalion anti-tank platoon (Captain N. L. Smith) in landing craft, tank, and the group reconnaissance party under Major Boehm in landing ship, infantry, the bulk of the marching troops of the beach group was due to embark in ten landing craft, infantry (large). These were long, narrow craft, carrying two hundred men apiece, fitted each with a pair of ramps that let down

on either side of the bow. With their lack of beam and shallow draught they rolled unpleasantly in a seaway, but the draught never seemed sufficiently shallow to give the troops aboard anything but the wettest of wet landings. The greater part of the group’s miscellaneous vehicles with their crews was shipped in considerably greater comfort in landing ships, tank, on to which they embarked from the hards in Gosport.

A staging had been erected on tubular scaffolding close to South Parade and the embarkation of men, handcarts and rations for the voyage proceeded without incident. As each landing craft, infantry, received its complement it set out to take up its station in the convoy.

The Solent presented an unforgettable sight. It was crowded with shipping. Every type of ship was there, from battleships to small assault craft, great ocean liners to rocket craft. It took a quarter-of-an-hour’s steaming to find our place in this convoy in Ryde Roads and there we anchored.

Although we had embarked it was by no means certain that we should sail. Even in the sheltered waters of the Solent the sea was choppy and as the day wore on the chances of sailing appeared to be growing less. But just before dark ships were seen to be moving, only a few at first, and then the bombardment squadron steamed past. Large liners carrying the assaulting infantry followed. The show was on. As dusk was falling a continual stream of shipping was to be seen moving out in long lines past the

Isle of Wight, making for “Piccadilly,” the rendezvous to the south-east of the island, and the open sea. All ranks turned in to enjoy what might be their last night’s unbroken sleep for some time to come.

6th June (D Day)

The second-tide convoy sailed at 0700 hrs. (H hour was at 0725 hrs.) and when we awoke we were at sea and in bright sunshine. The landing craft, infantry, were in line ahead, with the landing ships, tank, also in line ahead to port, and landing craft, tanks, towing anti-aircraft balloons on either quarter. Escorting warships could be seen farther out and the south coast of England was slipping past.

There was a heavy swell running and the shallow-draught landing craft, infantry, rolled and pitched. Those on board them envied the slow and majestic rolling of the landing ships, tank. A good breakfast was made, however, while the wireless informed us that an invasion force had landed on the coast of France. Soon afterwards, captains of craft received the signal to distribute maps, and these, showing for the first time the correct Normandy names, were distributed to those nominated—mostly

officers, and N.C.Os. down to serjeants. Messages from General Eisenhower and General Montgomery were read to the troops.

The coast of England faded away as the convoy turned south, and soon after lunch we entered the swept and buoyed channel leading to the beaches.

A message was signalled to all craft from the beach group commander stating that the assault was proceeding satisfactorily against opposition lighter than had been expected, and that No. 5 Beach Group had completed two exits from the beach.

Apart from returning craft, the first sign of action was the inspiring sight of H.M.S's. Rodney and Warspite lying apparently at anchor off our port quarter engaging the enemy batteries at Le Havre. Large clouds of white smoke billowed out from their sides as they fired broadside after broadside, and the shells could be seen clearly bursting on the hills above the town.

At 1900 hrs. the convoy reached a position approximately one mile off the Normandy coast opposite La Breche, and received a signal from the shore to anchor.

As the battalion approached the Normandy coast first impressions were of a flat

coastline with groups of houses dotted along its shore. On the eastern end the

lighthouse could be seen that marked the entrance to the Caen Canal and Ouistreham church, to the west the woods of Hermanville-sur Mer were recognised from the maps and aerial photographs.

The beach appeared to be deserted apart from bulldozers and small groups of men

constructing the beach lanes.

There was no sign of the balloons or windsocks used to mark the beach exits in training although some beach limit signs had been erected. Clouds of smoke from some of the burning sea front houses drifted inland and across the beach.

The beach was not under fire from the heavy guns at Le Havre so it looked as though plans B or C would not be used. The anchorage was crowded with craft of all sizes.

The Landing Craft Infantry (LCI) carrying the battalion lay at anchor for some thirty minutes before they were signalled to run in to the beach. Unfortunately some of the LCIs landed too far to the west of the beach and grounded in water that was too deep for disembarkation others lost their ramps as they had been lowered into the sea to soon throwing men into the sea. Those LCIs that had beached in deep water refloated and made another run in and the disembarkation began. But again they had beached in deep water six feet in places it was not a dry landing for many of the battalion.

As the battalion struggled ashore through the surf the Luftwaffe made an appearance and flew down the beach dropping a small bomb but was chased off by intense anti aircraft fire.

On wading ashore Lieutenant Colonel Sale the commanding officer was met at the water’s edge by Major Carse (2IC) and given the report that:-

(a) The 3rd British Division, after overrunning most of the beach defences, had pushed inland and was believed to have established a satisfactory bridgehead.

(b) The German strong-point at Lion-sur-Mer was still holding out in spite of two attacks by the 41 Commando.

(c) This strong-point commanded the main lateral road to the beach maintenance area, which was consequently unusable. Apart from that, there were believed to be German troops still in the area.

d) Lieutenant-Colonel Board, commanding No. 5Beach Group, was missing.

Although it was not known at the time, Lieutenant-Colonel Board had been killed by a German sniper soon after landing while making a reconnaissance on foot of the beach to the west, and command of his group had devolved on his second-in-command.

Lieutenant-Colonel Sale at once reported to beach sub-area command post which had been established on Queen/Red, and was ordered by Colonel Montgomery to take command of both beach groups forthwith. The sub-area commander confirmed the information supplied by Major Carse, and added that unloading into sector dumps was proceeding; but that until the strong-point at Lion was captured the beach maintenance area could not be used, and that an alternative plan had to be made before the large quantity of stores and the flood of men and vehicles arrived on D +1.

After a hasty reconnaissance the commanding officer met his own “0” group and explained the situation.:-

1. The carefully rehearsed drill was now impracticable and for the moment improvisation was imperative. Commanders would as soon as possible get their commands together and would tie up with their opposite numbers in No. 5Beach Group.

2. The beach companies would prepare to carry out their allotted task in opening fresh beaches to the east; petrol, supplies and ordnance would double-bank with No. 5 Beach Group installations in the sector stores dumps;

3. The field company, provost and R.E.M.E. would temporarily come under command of the opposite number in No. 5 Beach Group. C and D Company commanders were ordered to form protective flanks to the east and west respectively, the C Company to cover the lock gates at Ouistreham and D Company to guard against the threat of any attempted break-out from the Lion strong-point.

The tactical picture by dark on D Day was in fact this:

1. a bridgehead had been secured by the 3rd British Division approximately three miles deep, and the 8th Brigade was firmly established on the Periers ridge. Caen had not been captured and the division had met heavy opposition north of the Lebisey Wood, where it was checked by troops of the 21st Panzer Division.

2. Due to the most successful coup-de-main operation by the 52nd, the Benouville bridges had been captured intact at a very early stage and a bridgehead secured by the 6th Airborne Division to the east of the River Orne.

3. The division had then fanned out northwards, but had been stopped at the village of Sallenelles, which they had occupied.

4. Franceville Plage, however, was still held by the enemy, as were also the country and coast to the east of it.

5. Ouistreham had been cleared of the enemy, the locks being captured intact, and all country immediately to the west of the River Orne up to three miles inland was in our hands.

6. The left flank was thus protected by the double anti-tank obstacle of the River Orne and the Caen Canal, but there appeared to be no British troops at all east of the river near its mouth, as the result of the diversion of the leading commando of the 1st Special Service Brigade to Ranville. This commando had been detailed originally to deal with Franceville Plage.

7. To the west the strong-point at Lion-sur-Mer was holding out and there were snipers in the woods and houses adjoining it.

8. No junction had as yet been made with the 3rd Canadian Division.

Aircraft towing gliders carrying the “follow-up” troops of the 6th Airborne Division passed overhead just as dusk was falling and the troops were greatly heartened by this magnificent sight. The gliders landed to the south of Ouistreham and soon the returning tugs roared overhead in a seemingly endless stream from the south.

As troops could not be deployed to intended positions in the beach maintenance area, there was a good deal of disorganisation, but, following the commanding officer’s order group during the night, commanders collected most of their men successfully in temporary assembly areas. Snipers were still reported to be lurking in buildings overlooking the beach to the right, and as night fell a destroyer was firing Oerlikon shells into these houses, which blazed furiously and lit up the beach with a lurid glare.

During the night of the 6th/7th June German aircraft attacked the beaches in small numbers on several occasions dropping bombs which caused some casualties, but were driven off by heavy anti-aircraft fire from the shore and ships.

7th June (D+1) At his orders group the following morning the commanding officer stated that:

(a) Until the strong-point at Lion-sur-Mer could be captured the original plan was

not practicable and the beach maintenance area could not be established.

(b) Development of the beaches, vehicle and transit areas would proceed as originally planned.

(c) Sector stores dumps established in rear of the beaches would be enlarged to hold all stores landed.

(d) Traffic circuits would be adjusted accordingly.

Work now started in earnest. Entrances and exits were completed, beach roadway put down, signs erected, and an ever-growing stream of men, stores and vehicles began to pour ashore.

The dead were collected into reserve areas and covered, awaiting burial.

A command post between Red and White beaches was established.

The beach limits were properly marked.

Beach companies began to unload craft.

The Royal Navy began to sink their gooseberry.

In short, the operation really began to work, and by nightfall it was clear that the training had proved sufficiently practical to adapt itself to unforeseen circumstances.

During the morning of the 7th June an attack was launched by a company of the South Lancashire Regiment and 41 RM Commando against the Lion strongpoint but was unsuccessful in clearing the strongpoint, the South Lancs did however manage to mop up Plumetot and Cresserons two hamlets that were on the Southern edge of the Beach maintenance Area.

Two platoons of D Company 1st Bucks who had not landed the day before and had spent the night on board a Landing Ship Tank (LST) relieved the Commandos later in the day and secured the right flank of the beach area.

At 1100 hrs that morning eight Junkers Ju.88’s flew low in formation over the beaches from the direction of Franceville Plage, dropping butterfly bombs. They were greeted by a storm of anti-aircraft fire from the Bofors and Oeriikon guns, now well established ashore. Several were hit, and one fell almost on top of the sub-area command post, scattering its bombs in all directions. Apart from attacks by individual aircraft, there were no more determined raids in daylight. Raids by night continued for weeks to come.

8th June (D+2)

On the morning of D+2 the 9th Infantry Brigade, supported by tanks, artillery and the fire from a destroyer, launched an attack which was at last successful, and the strong-point at Lion was overrun. It consisted of fortified houses surrounded by concrete positions containing machine and anti-tank guns, minefields and flame-throwers. It was difficult to approach, as houses had been demolished to improve the field of fire of its garrison.

Unloading on the beaches was now approaching its maximum rate, and large quantities of stores were flowing into the four sector stores dumps. These had been established at intervals off the main lateral to the rear of the beaches. All the fields adjoining these dumps bore Achtung—Minen notices and the sappers of the field company, and anyone else who could be spared, were clearing the mines as fast as their many other duties would allow. But mine clearance is a slow process and in the meantime the dumps were becoming dangerously congested; petrol and ammunition were adjoining one another, and the stacks of ammunition were close together. Plans were, however, ready for expansion into the beach maintenance area as proposed

originally, and as soon as the strong-point at Lion fell reconnaissance parties left to inspect sites.

The prospects appeared good, a firm but narrow bridgehead had been secured, the weather was fine, the beach installations were established and developing at great speed, air attack was negligible, the beaches were not under fire, the ships forming the gooseberry could be seen settling down satisfactorily in their allotted places, and now it would be possible to establish the beach maintenance area in country, suitable for expansion and served by adequate roads.

At 1200 hrs a single German aircraft chased by Spitfires flew low over the main lateral, which was crowded with traffic, and dropped a bomb. A Dukw carrying petrol was hit and the burning petrol flowed down into an ammunition dump, which began to explode. Soon blazing petrol added a huge column of smoke and flame which roared skywards with a mushroom of smoke.

The stacks had been covered with camouflage netting, which caught alight easily; the grass was so dry that it burst into flame whenever red-hot fragments of metal landed and the result was that every stack that exploded started up a succession of new fires. Helped by a small band of officers and a handful of pioneers, Lieutenant Colonel Sale started to drag the nets from the stacks, beat out the blazing grass, drive out vehicles which had been abandoned by their drivers, and eventually, as more men were rallied, to demolish the stacks nearest to the seat of the fire so as to create a fire-break. For nearly an hour the party worked in this blazing inferno until Colonel Sale was hit in the stomach by a piece of flying shell and carried off unconscious to the nearest field dressing station. His place was taken by the second-in-command,

Major Carse. The fire burned itself out and half the dump was saved, with the result that when an urgent call for anti-tank ammunition was received that evening from the 3rd British Division the call was answered and the ammunition supplied. But 400 tons of precious ammunition and 60,000 gallons of petrol had been lost.

The loss of the commanding officer was a high price to pay for this achievement,

but his legacy remained, he had welded the beach group into a functioning formation. On landing he had taken command of 7,000 troops, revised the original plan and laid the foundations for the groups future success. For his actions on the 8th June he was awarded the George Medal for his gallantry.

Soon after this incident German shelling of the beaches began and there was some talk of closing down the beaches on account of the increasing shelling, placing all troops on half-rations and relying on the beaches out of range farther to the west. This was vigorously opposed by the commander of Force S Rear Admiral A G Talbot who exclaimed “You can’t do that!” “Why, I’ve just sunk my gooseberry! Shelling! Why of course there’s shelling; this is war! Show me where the guns are and I’ll paste ‘em!” Soon after his return to his flagship the guns of the Rodneycould be heard

engaging the offending batteries, but apparently with little success, as the shelling

remained a constant daily feature of the battalions residence on Sword sector until the end of the Falaise battle two months later.

The coast from Franceville Plage to Deauville curves round in a great crescent with high ground at Houlgate. From this high ground the enemy could observe our beaches. There were estimated to be forty guns in concrete positions in this area capable of firing on Sword sector, varying in calibre from small guns up to 11-inch. Moreover, until the enemy was pushed back beyond Caen on the 8th July fire could be brought to bear from the batteries behind Lebisey Wood, and the beaches were often shelled from two directions simultaneously.

Until a replacement could be found for the commanding officer of 5th Kings (No 5 Group) it was decided by the sub area commander that both groups would be under the command of Major Carse (1Bucks) who was immediately promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. Major Boehm was appointed second-in-command.

9th June (D+3)

The dumps reopened on D+3 in the beach maintenance area on the sites allotted in the first key plan (Plan A).

12th June (D+6)

On the 12th June Lieutenant-Colonel Wreford Brown arrived to act as commander of No. 5 Beach Group and the headquarters of No. 6 Beach Group was moved to Lion-sur-Mer and responsibility for the beaches was handed over. No. 6 Beach Group and the battalion were now solely responsible for the beach maintenance area, but A and B Companies, 1st Bucks, who were working the beaches, remained under command of No. 5 Beach Group.

A few miles inland, the 3rd British Division remained locked with its adversaries on the threshold of Caen. No great change had, in fact, occurred in the positions of the combatants since the evening of D Day. All three infantry brigades were now in the line, with the 9th Brigade on the right in the area of Cambes, where it linked with the Canadians, the 8th Brigade in the centre at Le Mesnil Wood and the 185th Brigade on the left from Bieville to the river. In its bridgehead across the Orne the 6th Airborne Division, now reinforced by the 51st (Highland) Division, was steadily but slowly expanding and beating off a succession of German counter-attacks with the aid of the divisional artillery of the 3rd Division. The Montgomery plan of attracting the weight of the German armour to the hinge at Caen was pursuing its preordained course.

16th June (D+10)

On the 16th June, while Queen beach was being shelled heavily, six out of seven landing craft, tank, beached at the time were hit. At 2000 hrs on this day a Spitfire crashed in the petrol dump, setting petrol alight. Miraculously the pilot was saved before being burnt, and the fire put out.

Things were now going so well that it was intended to replace the labour provided by the Battalion with pioneers and move the Battalion to Ouistreham so that it could protect the locks.

As a result of the speed with which the 6th Airborne Division had attacked on D Day

these locks at the entrance to the Caen Canal had been captured undamaged, and

as it was planned to use the docks of Caen as a principal supply port as soon as

the town was captured, it was vital that these locks should remain intact.

In spite of the foothold won by the 6th Airborne Division on the east bank of the River Orne it had not been possible to drive the Germans from Franceville Plage at the mouth of the Orne. The 6th Airborne Division, in fact, was hard put to it to maintain the ground which it had won, and great battles were raging at Ranville and Herouvillette. In consequence the enemy were only 3,000 yards from the docks, with no intervening troops, and it was considered probable that they would make a raid to demolish the gates and pumping machinery.

On the 16th June C Company was withdrawn from the ammunition dump and moved

to defensive positions on the strip of ground between the locks and the entrance to the Orne. On the same day an enemy aircraft attempting to bomb the locks was shot down.

The following day D Company, the reserve working company, was moved to Ouistreham, where it combined the duties of a reserve to C Company and the administration of Moon assembly area, a transit area used for the passage of troops and vehicles to the line.

18th June (D+12)

On the 18th June Battalion headquarters moved to its new position in Riva Bella and on the 22nd the remainder of the Battalion moved into Ouistreham and Riva Bella and complete responsibility for the ground and air defence of the locks was assumed. So

for all practical purposes, after only twelve days of active operations, No. 6 Beach Group ceased to exist, although it continued to live on paper for another three weeks, and the Battalion reverted to an infantry role.

The weather since the flurry of the 5th June, had been remarkably good, but now came the storm which for four days, from the 19th to the 22nd June, practically immobilised the beaches. Valiant efforts were made by the Navy and the Dukw companies to keep the vital flow going, but it was of no avail.

On the 18th June nearly 200 vehicles and well over 2,300 tons of stores had been passed over No. 101 Beach Sub-Area beaches. On the 19th June no vehicles and 314 tons of stores were landed, and on the next day only 650 tons. Tonnages of this nature were wholly insufficient to maintain the troops already ashore, and as a third and yet a fourth day of gales followed, faces began to assume a worried air. Stocks however, had been so well built up during the earlier fine period that forward troops were in no way affected by the almost complete stoppage of supplies and by the night of the 22nd June (D plus 16) the storm had blown itself out.

On the 23rd the stream was beginning to flow again and 169 vehicles and 1,321 tons of supplies crossed the beaches.

Shelling of the locks and powerhouse had now become a daily feature, but no serious damage was done.

24th June (D+18)

A party including the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsey, and other naval officers ascended the lighthouse at the entrance to the canal on the 24th and there was considerable anxiety at the sight of so much brass being exhibited to the enemy. Luckily he failed to react, although shortly afterwards he secured two direct hits on the lighthouse with an anti-tank gun.

More aircraft dropped bombs on the night of the 24th/25th June, one of which narrowly missed the gates.

The shooting of the German gunners was excellent. On the 26th they hit the walls of the lock but missed the gates, and when a foolish driver of a three-ton lorry, belonging to the R.A.S.C., parked it in full view of the enemy they secured a direct hit with their second shell.

The plan for the defence of the locks was now as follows:

(a) One rifle company (and the mortar platoon) on the ground to the east of the power-house to prevent a raid from the Point du Siege.

(b) One rifle company to the west of the canal (supported by a neighbouring pioneer company) to prevent the enemy crossing the canal farther to the south.

(c) One rifle company in Ouistreham ready to counterattack any enemy who gained a foothold on the west bank.

(d) One rifle company in reserve in Riva Bella.

(e) Anti-tank platoon guarding west bank of the canal.

(f) Artillery support from I Corps.

Companies moved round at intervals and occupied each of these positions during the ensuing weeks. Those given in sub-paragraphs (a) and (b) were the hottest positions, and always under an intermittent fire. Patrols were sent by night to the end of the Point du Siege, where snipers were left to pick off any Germans seen by day on the opposite side of the Orne.

An intelligence observation post was established in a bunker on the west bank of the canal with a good view of the enemy positions, and passed back much useful information. It was then manned by Cpl Toogood and thereafter codenamed “Toogood”. The bunker had a thick steel cupola and its machine guns covered the entrance to the canal and the beach eastwards to the mouth of the River Orne, the other side of which was occupied by the enemy. A road ran from the canal bridge parallel to the beach and ended at the Orne. It was from this position that two sniper posts were set up. These were dug in deep, sandbagged and with firing apertures through the river embankment facing towards the enemy on the opposite side.

18th June (D+12)

On the 18th June Battalion headquarters moved to its new position in Riva Bella and on the 22nd the remainder of the Battalion moved into Ouistreham and Riva Bella and complete responsibility for the ground and air defence of the locks was assumed. So

for all practical purposes, after only twelve days of active operations, No. 6 Beach Group ceased to exist, although it continued to live on paper for another three weeks, and the Battalion reverted to an infantry role.

The weather since the flurry of the 5th June, had been remarkably good, but now came the storm which for four days, from the 19th to the 22nd June, practically immobilised the beaches. Valiant efforts were made by the Navy and the Dukw companies to keep the vital flow going, but it was of no avail.

On the 18th June nearly 200 vehicles and well over 2,300 tons of stores had been passed over No. 101 Beach Sub-Area beaches. On the 19th June no vehicles and 314 tons of stores were landed, and on the next day only 650 tons. Tonnages of this nature were wholly insufficient to maintain the troops already ashore, and as a third and yet a fourth day of gales followed, faces began to assume a worried air. Stocks however, had been so well built up during the earlier fine period that forward troops were in no way affected by the almost complete stoppage of supplies and by the night of the 22nd June (D plus 16) the storm had blown itself out.

On the 23rd the stream was beginning to flow again and 169 vehicles and 1,321 tons of supplies crossed the beaches.

Shelling of the locks and powerhouse had now become a daily feature, but no serious damage was done.

24th June (D+18)

A party including the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsey, and other naval officers ascended the lighthouse at the entrance to the canal on the 24th and there was considerable anxiety at the sight of so much brass being exhibited to the enemy. Luckily he failed to react, although shortly afterwards he secured two direct hits on the lighthouse with an anti-tank gun.

More aircraft dropped bombs on the night of the 24th/25th June, one of which narrowly missed the gates.

The shooting of the German gunners was excellent. On the 26th they hit the walls of the lock but missed the gates, and when a foolish driver of a three-ton lorry, belonging to the R.A.S.C., parked it in full view of the enemy they secured a direct hit with their second shell.

The plan for the defence of the locks was now as follows:

(a) One rifle company (and the mortar platoon) on the ground to the east of the power-house to prevent a raid from the Point du Siege.

(b) One rifle company to the west of the canal (supported by a neighbouring pioneer company) to prevent the enemy crossing the canal farther to the south.

(c) One rifle company in Ouistreham ready to counterattack any enemy who gained a foothold on the west bank.

(d) One rifle company in reserve in Riva Bella.

(e) Anti-tank platoon guarding west bank of the canal.

(f) Artillery support from I Corps.

Companies moved round at intervals and occupied each of these positions during the ensuing weeks. Those given in sub-paragraphs (a) and (b) were the hottest positions, and always under an intermittent fire. Patrols were sent by night to the end of the Point du Siege, where snipers were left to pick off any Germans seen by day on the opposite side of the Orne.

An intelligence observation post was established in a bunker on the west bank of the canal with a good view of the enemy positions, and passed back much useful information. It was then manned by Cpl Toogood and thereafter codenamed “Toogood”. The bunker had a thick steel cupola and its machine guns covered the entrance to the canal and the beach eastwards to the mouth of the River Orne, the other side of which was occupied by the enemy. A road ran from the canal bridge parallel to the beach and ended at the Orne. It was from this position that two sniper posts were set up. These were dug in deep, sandbagged and with firing apertures through the river embankment facing towards the enemy on the opposite side.

Constant efforts were made by artillery of I Corps to silence the enemy guns. Counter-battery fire was produced as soon as the German guns fired, but with little effect, as they were well protected and as many as four alternative positions existed for each

gun.

10th July

On the 10th July No. 6 Beach Group was dissolved officially. It had, in fact, disintegrated before this date, as its components had passed one by one to the command of higher formations. For the first time since the 5th April, 1943, Battalion

headquarters was left with only the Battalion to command.

The success of the beach group had exceeded expectations. The critical period between the assault and the full operation of the Mulberry harbour on D+30 had been bridged, and casualties had been low in comparison with those expected.

12th July

All movement over Sword beaches finally ceased on the 12th July and craft were transferred to the comparative peace and safety of Juno and Gold sectors farther to the west.

Between D Day and the closing of the beaches on D+34, 46,644 men, 7,677 vehicles and 59,228 tons of stores had been safely landed.

Now that the Battalion had been finally withdrawn from the beach group and the group itself was no more, every effort was made to press on with some infantry training. It had always been the hope since the Battalion joined the beach group that it would one day have a chance to prove its worth as an infantry battalion proper. Opportunities for infantry training during the beach group role had been few and with the Germans only 800 yards away in some places perhaps it was an odd time to start training, but Lieutenant Colonel Carse was extremely anxious to get the Battalion attached to the 6th Airborne Division if possible and was quite determined to get it in fighting trim with the least possible delay and make the most of every opportunity.

The battalions only front-line commitment at the time was one company defending the canal and Ouistreham locks, and to ensure that as many of the Battalion as possible got some experience of front-line warfare this company was relieved every ten days. Every company had a spell during their stay there and experienced considerable enemy shell fire. Company reliefs were carried out at night with little or no interference from the enemy.

Enemy shelling from the Franceville Plage area was a regular daily feature and seemed to be directed at Ouistreham generally rather than at any particular objective.

About this time a big drive for volunteers for the airborne division and commandos started, and representatives from both formations came round asking for names. Quite a number of the men volunteered, but on the whole they seemed to prefer to stay with the Battalion in the hope that they might all see action together.

The future of the Battalion was very much in the minds of everyone during this time, as it was understood that the reinforcement position was becoming difficult and that some battalions were being disbanded to provide replacements. For beach group

battalions especially the outlook did not look good.

As time went by and news filtered through that the other beach battalions had received orders to disband, it seemed that the battalions fate would be the same, but still no definite instructions were received. Colonel Carse spent most of his time visiting every conceivable headquarters and stating the case of the Battalion, pointing out that it was an original Territorial battalion, that it was in fact at present carrying out an operational role, and trying to persuade the powers-that-be to put the battalion under command of the 6th Airborne Division for operations. If this could be done the battalions future might well be assured and hopes of becoming a fighting battalion at last realised.

The blow finally fell a few days later when the battalion was officially informed in a letter from General Montgomery that it was to become a drafting battalion

The battalion now knew what was in store for it and managed to draw some consolation from the fact that it to remain as the “Bucks.” and would not be disbanded. The battalion would be put in a state of“suspended animation” and be provided with a minimum cadre in due course. A date when drafting would start was not clear, but the establishment would be frozen whilst performing the role of the defence of Ouistreham.

During the next two weeks very little of importance occurred. The rifle companies guarding the entrance to the canal continued to rotate; the 3-inch mortars put in some effective shoots on the enemy on the other side of the canal and made the inevitable reply. All were so used to this by now and the “take cover” drill was so well organised that casualties were extremely few.

During this period the commanding officer had renewed his activities for getting the Battalion taken out of line of communications and attached to the airborne division. He considered that, although the die had been cast on the battalions eventual future, there was no conceivable reason why in the interim it should not enjoy a more active role, and he was determined to do all he could to get the battalion under the wing of a fighting division. In this he had the full approval and backing of the G.O.C., 6th Airborne Division (Major-General R. N. Gale), who was most keen to take the Battalion over, as his division was extremely thin on the ground. The G.O.C. himself made many representations to the staff of I Corps, and the result of his efforts appeared on the 30th July, when the Battalion was officially placed under command of the First Canadian Army with effect from 1200 hrs that day.

Lieutenant Colonel Carse lost no time in visiting headquarters, I Corps, and arranged for the Battalion to be directly under I Corps for administration and under the 6th Airborne Division for operations.

31st July

By the following day, the 31st July, it had been arranged for B Company to move over the River Orne to take up defence positions under command of the 52nd, while A Company assumed responsibility for guarding four bridges over the River Orne under command of the 4th Special Service Brigade. Everyone was in high spirits over this

sudden change of role. The airborne staff was delighted to see the Battalion, and was determined to help it. The divisional commander himself came to Battalion headquarters and had a look round the defences on the docks, and discussed the future operational role. The antitank and carrier platoons were put under direct command of headquarters. 6th Airborne Division.

On the 1st August a letter was received from Colonel Montgomery, No. 101 Beach Sub-Area, thanking everyone for his good work and loyal co-operation. Following this and the recent change of command, all beach group signs were removed from uniforms and vehicles pending a decision on what sign was to be worn in the future.

3rd August

On the evening of the 3rd August, after a day of heavy shelling throughout the area the enemy started to concentrate on the docks and shells fell thick and fast round the mortar platoon and C Company, which had a few hours previously taken over from D Company. Reports came into Battalion headquarters that the shelling was intense and that one man had been killed. Colonel Carse, on hearing this, decided to visit the company immediately. On arrival there he parked the jeep under some trees and was walking towards C Company along the side of the road when a shell exploded some ten yards from him. The blast threw him to the ground and a splinter pierced his leg.

He was taken to the 6th Canadian Hospital immediately for treatment, and was evacuated to England shortly afterwards.

His loss was felt deeply by all ranks, he had staved off disbandment and had been the direct cause of the battalion’s attachment to the 6th Airborne Division. Perhaps it was as well that he did not stay to see the break-up of the old Battalion. He was so much a man of action and unbounded energy that it would probably have broken his heart to find himself commanding a battalion of categorised men. This unfortunate lot was

to fall on the second-in-command, Major Boehm, who immediately assumed command of the Battalion.

7th August

Instructions were now received from the 6th Airborne Division that a further company was required on the other side of the River Orne with effect from the 7th August. It was accordingly decided to replace A Company on the bridges by two platoons of

D Company and to send A Company into the new position. This was done and A Company came under the 49th Reconnaissance Regiment for this particular operation.

A Company was to act as longstop to the reconnaissance regiment in case of any break-through.

10th August

On the 10th August a further company was required to come under command of the 102nd Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment. A Company, being now no longer needed in support of the 49th Reconnaissance Regiment, was withdrawn to its original position guarding the bridges (York bridge in particular) and D Company was sent to the 102nd Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, taking up its headquarters in a farm near

Ranville. This meant that all companies were now operationally committed:-

A on the bridges under the commandos,

B under the 52nd,

C on the canal,

D under the 102nd Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment,

and the anti-tank and carrier platoons under headquarters, 6th Airborne Division--

leaving as a reserve: Battalion headquarters, H.Q. Company and the balance of S Company headquarters and a few of the pioneer platoon.

12th August

A sudden change of plan by the 6th Airborne Division meant that D Company was no longer required at Ranville and it was accordingly drawn into reserve and then sent to relieve A Company once more on the bridges to enable the latter to come into the rest area and clean up. This was the position of companies when at 2230 hrs on the 12th August the battalion were advised by I Corps that it had to supply a draft of three officers (including one captain) and 150 other ranks to the 7th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders by 1000 hrs the following morning.

Although the battalion had known for some time that this was going to happen, such forewarning did not soften the blow when it actually came. Encouraged by the hope that as the battalion was under the operational command of the 6th Airborne Division it might be saved from drafting and be allowed to fight with it as a battalion. It came as a shock to realise that its hopes had been unfounded and that it was back where it had been on receipt of General Montgomery’s letter, with the one difference that whereas then the sword was hanging over their heads now it had fallen and had exactly eleven and a half hours in which to execute the first demand.

After consultation with the 6th Airborne Division it was agreed that the draft would be found from A and D Companies. The two company commanders were called into conference at 0030 hrs and it was decided that A Company should go complete—this would provide ninety officers and men—the balance to be made up from D Company (2 platoons). The officers were to be Captain Hope, Lieutenant Hands of A Company, and (as no subalterns were available in D Company) Lieutenant Shilling from C Company as the third.

Now that drafting had started there was no object in keeping back any particular officer or N.C.O., as in the end all would undoubtedly have to go and it was therefore decided to write off companies one by one and ensure that as far as possible they went en bloc with their officers. This, perhaps, would not always be possible, as the size of the draft required would vary, but it was agreed that at least platoons with their own platoon officers should be kept together.

With the backing of the 6th Airborne Division the commanding officer obtained four hours’ grace from corps to give D Company time to withdraw their platoons from the bridges at dawn and prepare for the move, and corps accordingly arranged for transport from the 51st Division to report to the Battalion at 1400 hrs on the 13th August to collect the men.

A and D Companies embussed punctually at 1400 hrs and were ready to move off. The troops seemed in excellent spirits, many of them already imitating the Scottish tongue. They thought highly of the 51st Division, and as they had already been warned of the probable fate of their own Battalion were pleased to be going to a good

regiment rather than a reinforcement holding unit, and even more pleased to be all going together.

No policy could be dragged out of higher formation about future commitments or role, except that it was proposed to move the battalion into a concentration area near the corps reception camp so that it would be available more easily.

Late on the 14th August the battalion was told by I Corps that it was to move to Cresserons the next day. Immediate arrangements were made with the 6th Airborne Division for the release of B Company, the carrier platoon and the anti-tank platoon, and also for the taking over from C Company of the dock commitments. A Company of the 12th Parachute Battalion took over the latter duties after a rapid reconnaissance the following morning.

15th August

The quartermaster was sent off early in the day to find a suitable area, and as the move was only short it was arranged to lift one company at a time in the Battalion transport. By 1800 hrs the whole Battalion had been transported to the new position, which was actually just outside Cresserons in a small village called Plumetot, which had figured in the original first key plan of the beach maintenance area.

There were few buildings available and each company was allotted a large field in which to dig bivouacs and set up office tents and the like. We still retained our beach group tents. Battalion headquarters were in an orchard. Luckily the weather was fine and the evenings long, and everyone was settled in before dark.

Just before the headquarters were closed down at Ouistreham a telephone call was received from I Corps saying we were expected to provide a further draft of eight officers and one hundred other ranks for the 1st Black Watch by 1900 hrs that night. Without soliciting anyone’s advice the adjutant stated that it could not be done, as the Battalion was on the move, but guaranteed to have the draft ready by 1100 hrs the following day, the 16th August. This was agreed.

The draft of 3 subalterns and 100 men was found from 'C' Coy (2 Pls) and 'D' Coy (1 Pl).

After the provision of this draft the rifle-company position was:

A Company: headquarters only.

B Company: complete.

C Company: headquarters and one platoon.

D Company: headquarters only.

16th August

The draft went off according to the war diary in “high spirits” in transport supplied once again by the 51st Division. It was most heartening to see the excellent spirits and bearing of the men—now, alas, stripped of the familiar red and black chevrons and badges. The 51st Division were undoubtedly receiving a first-class reinforcement.

Later that morning the battalion was informed by I Corps that it was allowed to retain as its minimum cadre five officers and one hundred other ranks, with twelve vehicles.

18th August

The drafting process continued on the 18th with drafts for the lst/4th King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (49th Division) (1 officer and 1 platoon C Coy) and the 5th Seaforth Highlanders (2 officers & 2 platoons B Coy) from B and C Companies.

Apart from one platoon of B Company and the four rifle company headquarters, the Battalion was now left with specialists only, and a special visit was paid to I Corps, where the policy was firmly established that specialist officers would only be drafted to specialist jobs and not as rifle platoon commanders. Similarly, specialist soldiers would not be drafted as riflemen.

20th August

The commanding officer on his last visit to corps had managed to glean the following information about the battalion’s future:

(a) likely to be made into a garrison battalion.

(b) 21st Army Group were preparing a minimum cadre for the battalion.

(c) Battalion would remain in present position until further notice.

During the next few days information about the battalions future was sought from every conceivable source.

As a last hope a call was made on Colonel Montgomery at No. 101 Beach Sub-Area, now at Port en Bessins. He took the commanding officer to see headquarters, Line of Communications, where it was discovered that the Battalion had been under line of communications since 1200 hrs the previous day. After pressing for further information Colonel Boehm discovered that line of communications were preparing the minimum cadre and that the Battalion was eventually to be made up with categorised men and “bomb-happies.” At last the ghastly truth was out. The Battalion was to be left with nine officers (including company commanders) and seventy-two soldiers, but no support company. When the cadre had been chosen six officers and two hundred soldiers were left for disposal.

26th August 1944

0900 -Conference for commanders and details of drafts given out.

27th August

At 1000 hrs on the 27th August the last draft departed.

1 Gordons 4 Officers & 78 Ors

5 Black Watch 1 Officer

5/7 Gordons 14 ORs

152 Inf Bde HQ 3 ORs

2 Seaforths 29 ORs

5 Seaforths 23 ORs

5 Camerons 1Officer & 22 ORs

Totals 6 Officers 169 ORs

The last parade of the Battalion, which was formed after the losses at Dunkirk, took place in a field adjoining the orchard at Plumetot, in which Battalion headquarters had been established. The Regimental Serjeant-Major put out markers, each of whom represented a draft for a battalion of the Highland division.

The Battalion had been amongst the earliest troops to land in the bridgehead, had worked the beaches, often under fire, and had maintained, with its companions, one-quarter of a British army in the early stages of the most intricate and hazardous operation in military history.

Complete disbandment was the fate of many good battalions at this time in face of the urgent need for reinforcements and the Battalion was fortunate in being left a cadre from which a new battalion could be built.

The men who were about to leave were to join a famous division with the promise that they would be employed in the roles for which they had been trained. Many reports were received during the following months showing that the 1st Buckinghamshire Battalion was respected in the Highland division.

1. The Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry Chronicle, Vol 4: June 1944 - December 1945 Pages 117-150

Proudly powered by Weebly