- HOME

- SOLDIER RESEARCH

- WOLVERTONS AMATEUR MILITARY TRADITION

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE RIFLE VOLUNTEERS 1859-1908

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BATTALION 1908-1947

- The Bucks Battalion A Brief History

- REGIMENTAL MARCH

-

1ST BUCKS 1914-1919

>

- 1914-15 1/1ST BUCKS MOBILISATION

- 1915 1/1ST BUCKS PLOEGSTEERT

- 1915-16 1/1st BUCKS HEBUTERNE

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS SOMME JULY 1916

- 1916 1/1st BUCKS POZIERES WAR DIARY 17-25 JULY

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS SOMME AUGUST 1916

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS LE SARS TO CAPPY

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS THE GERMAN RETIREMENT

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS TOMBOIS FARM

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS THE HINDENBURG LINE

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS 3RD BATTLE OF YPRES

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES 16th AUGUST

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES WAR DIARY 15-17 JULY

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS 3RD BATTLE OF YPRES - VIMY

- 1917-18 1/1ST BUCKS ITALY

-

2ND BUCKS 1914-1918

>

- 1914-1916 2ND BUCKS FORMATION & TRAINING

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS ARRIVAL IN FRANCE

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS FROMELLES

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS REORGANISATION

- 1916-1917 2/1st BUCKS THE SOMME

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS THE GERMAN RETIREMENT

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS ST QUENTIN APRIL TO AUGUST 1917

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS ARRAS & CAMBRAI

- 1918 2/1st BUCKS ST QUENTIN TO DISBANDMENT

-

1ST BUCKS 1939-1945

>

- 1939-1940 1BUCKS MOBILISATION & NEWBURY

- 1940 1BUCKS FRANCE & BELGIUM

- 1940 1BUCKS HAZEBROUCK

- HAZEBROUCK BATTLEFIELD VISIT

- 1940-1942 1BUCKS

- 1943-1944 1BUCKS PREPARING FOR D DAY

- COMPOSITION & ROLE OF BEACH GROUP

- BROAD OUTLINE OF OPERATION OVERLORD

- 1944 1ST BUCKS NORMANDY D DAY

- 1944 1BUCKS 1944 NORMANDY TO BRUSSELS (LOC)

- Sword Beach Gallery

- 1945 1BUCKS 1945 FEBRUARY-JUNE T FORCE 1st (CDN) ARMY

- 1945 1BUCKS 1945 FEBRUARY-JUNE T FORCE 2ND BRITISH ARMY

- 1945 1BUCKS JUNE 1945 TO AUGUST 1946

- BUCKS BATTALION BADGES

- BUCKS BATTALION SHOULDER TITLES 1908-1946

- 1939-1945 BUCKS BATTALION DRESS >

- ROYAL BUCKS KINGS OWN MILITIA

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE'S LINE REGIMENTS

- ROYAL GREEN JACKETS

- OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1965

- OXF & BUCKS LI INSIGNIA >

- REGIMENTAL CUSTOMS & TRADITIONS >

- REGIMENTAL COLLECT AND PRAYER

- OXF & BUCKS LI REGIMENTAL MARCHES

- REGIMENTAL DRILL >

-

REGIMENTAL DRESS

>

- REGIMENTAL UNIFORM 1741-1896

- REGIMENTAL UNIFORM 1741-1914

- 1894 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1897 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1900 DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1931 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1939-1945 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1950 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1960 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS (TA)

- 1960 REGIMENTAL MESS DRESS

- 1963 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1958-1969 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- HEADDRESS >

- REGIMENTAL CREST

- BATTLE HONOURS

- REGIMENTAL COLOURS >

- BRIEF HISTORY

- REGIMENTAL CHAPEL, OXFORD >

-

THE GREAT WAR 1914-1918

>

- REGIMENTAL BATTLE HONOURS 1914-1919

- OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY INTRODUCTION

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY

- 1/4 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 2/4 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 1/1 BUCKS BATTALION 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 2/1 BUCKS BATTALION 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 5 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 6 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 7 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 8 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 1st GREEN JACKETS (43rd & 52nd) 1958-1965

- 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND) 1958-1965

- 1959 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1959 REGIMENTAL MARCH IN OXFORD

- 1959 DEMONSTRATION BATTALION

- 1960 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1961 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1961 THE LONGEST DAY

- 1962 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1963 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1963 CONVERSION TO “RIFLE” REGIMENT

- 1964 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1965 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1965 FORMATION OF ROYAL GREEN JACKETS

- REGULAR BATTALIONS 1741-1958

-

1st BATTALION (43rd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

-

43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1914

>

- 43rd REGIMENT 1741-1802

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1803-1805

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1806-1809

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1809-1810

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1810-1812

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1812-1814

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1814-1818

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1818-1854

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1854-1863

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1863-1865

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1865-1897

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1899-1902

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1902-1914

-

1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919

>

-

1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1920-1939

>

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1920

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1921

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1922

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1923

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1924

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1925

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1926

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1927

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1928

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1929

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1930

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1931

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1932

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1933

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1934

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1935

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1936

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1937

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1938

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1939

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945 >

-

1 OXF & BUCKS 1946-1958

>

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1946

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1947

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1948

- 1948 FREEDOM PARADES

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1949

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1950

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1951

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1952

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1953

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1954

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1955

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1956

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1957

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1958

-

43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1914

>

-

2nd BATTALION (52nd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

- 52nd LIGHT INFANTRY 1755-1881 >

- 2 OXF LI 1881-1907

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1908-1914

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919

>

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919-1939

>

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1920

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1921

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1922

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1923

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1924

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1925

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1926

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1927

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1928

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1929

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1930

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1931

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1932

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1933

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1934

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1935

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1936

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1937

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1938

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1939

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945

>

- 1939-1941

- 1941-1943 AIRBORNE INFANTRY

- 1944 PREPARATION FOR D DAY

- 1944 PEGASUS BRIDGE-COUP DE MAIN

- Pegasus Bridge Gallery

- Horsa Bridge Gallery

- COUP DE MAIN NOMINAL ROLL

- MAJOR HOWARDS ORDERS

- 1944 JUNE 6

- D DAY ORDERS

- 1944 JUNE 7-13 ESCOVILLE & HEROUVILETTE

- Escoville & Herouvillette Gallery

- 1944 JUNE 13-AUGUST 16 HOLDING THE BRIDGEHEAD

- 1944 AUGUST 17-31 "PADDLE" TO THE SEINE

- "Paddle To The Seine" Gallery

- 1944 SEPTEMBER ARNHEM

- OPERATION PEGASUS 1

- 1944/45 ARDENNES

- 1945 RHINE CROSSING

- OPERATION VARSITY - ORDERS

- OPERATION VARSITY BATTLEFIELD VISIT

- 1945 MARCH-JUNE

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI DRESS 1940-1945 >

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1946-1947 >

-

1st BATTALION (43rd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

- MILITIA BATTALIONS

- TERRITORIAL BATTALIONS

- WAR RAISED/SERVICE BATTALIONS 1914-18 & 1939-45

-

5th, 6th, 7th & 8th (SERVICE) 1914-1918

>

-

6th & 7th Bns OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945

>

- 6th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI 1940-1945 >

-

7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI 1940-1945

>

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1940-JULY 1942

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JULY 1942 – JUNE 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JULY 1943–OCTOBER 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI OCTOBER 1943–DECEMBER 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI DECEMBER 1943-JUNE 1944

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JANUARY 1944-JUNE 1944

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1944–JANUARY 1945

-

5th, 6th, 7th & 8th (SERVICE) 1914-1918

>

- "IN MY OWN WORDS"

- CREDITS

FIRST BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BATTALION

HEBUTERNE

June 1915 to June 1916

BASED ON EXTRACTS FROM CITIZEN SOLDIERS OF BUCKS BY JC SWANN AND THE FIRST BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BATTALION 1914-1919 BY PL WRIGHT

Shortly before the Battalion moved from Ploegsteert Major-General Heath was compelled by ill-health to vacate the Command of the 48th Division, and Major-General R. Fanshawe, C.B., D.S.O. (52nd Light Infantry) was appointed to succeed him.

There followed a series of three night marches, via Vieux-Berquin, Merville,

Busnettes, to Allouagne, which lies five miles west of Bethune

The billets at Allouagne were the best the battalion had seen, and a happy fortnight was spent here. Training was strenuous and carried out mostly in a neighbouring wood, called the Bois de Maraquet.

On the 12th July, the Battalion was moved in to bivouacs close to Noeux-les-Mines, every man available during the two succeeding days being put on to digging a new rear line. It was thought that the Division was to take over new trenches in this area but on July 16 the battalion suddenly got orders to move, and marched the whole of that night, in a deluge of rain, to billets in Lieres, passing within a stone’s throw of Allouagne.

On the 18th the battalion were put into a train at Berguette, which slowly

proceeded to Doullens. A two hours’ march from there took the battalion to some woods at Marieux, where it arrived at 4 a.m. to bivouac.

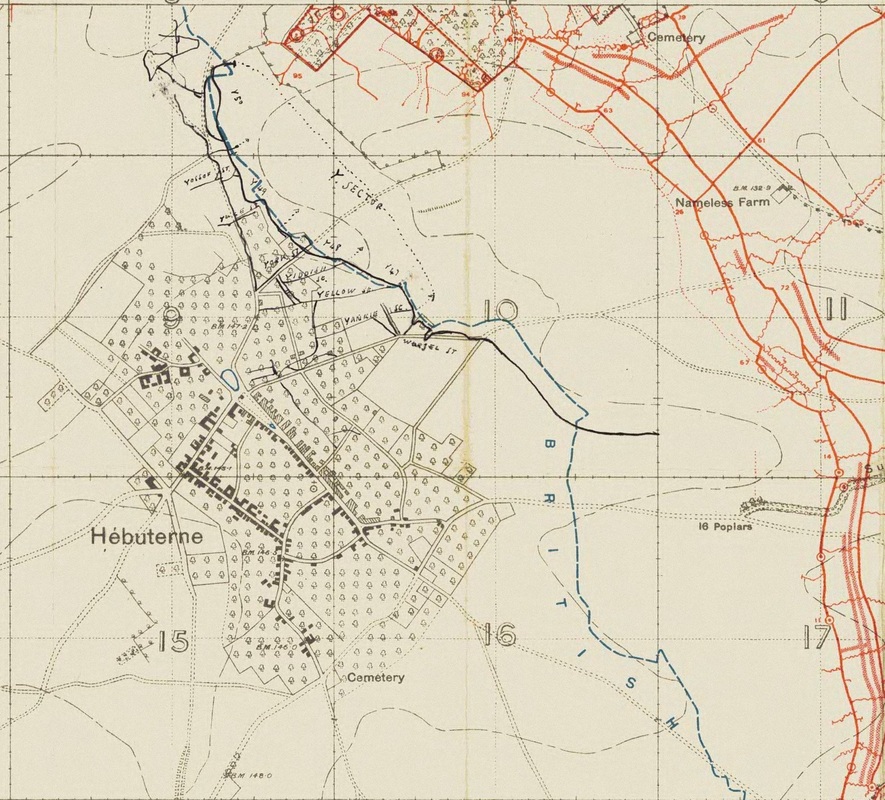

On July 20, the 48th Division started to relieve the French in the line in front of the village of Hebuterne, the Bucks Battalion being in reserve, with two companies at Sailly-au-Bois and two companies at Bayencourt. Both these villages were then a mass of flies, owing to the general filth everywhere, and, as the weather was extremely hot, life in these billets was none too pleasant.

The trenches, which the Battalion took over on July 24, lay some 100 to 300 yards east of Hebuterne and were at this time good and quiet. Unlike the front line at Ploegsteert, where the trenches consisted of sandbagged barricades, these trenches were dug down about 6 feet deep all along.

The enemy’s trenches were from 300 to 1,000 yards distant, instead of being within 100 to 200 yards as at Ploegsteert. For about a fortnight the Division was supported by French guns, with apparently no shortage of ammunition. They were always able to send back three times as many shells as the enemy had given to our front trenches, and they were much missed by the Infantry when they were relieved by our own artillery, still bound to economy in the matter of ammunition.

The dugouts had the outward appearance of real luxury, owing to a large portion of the furniture of Hebuterne having been imported into them. Four-poster beds existed in quite a number, but owing to the quantities of small vermin and mice which had made their homes in them, they proved to be most undesirable, and were almost all scrapped before the battalion had been a week in the line.

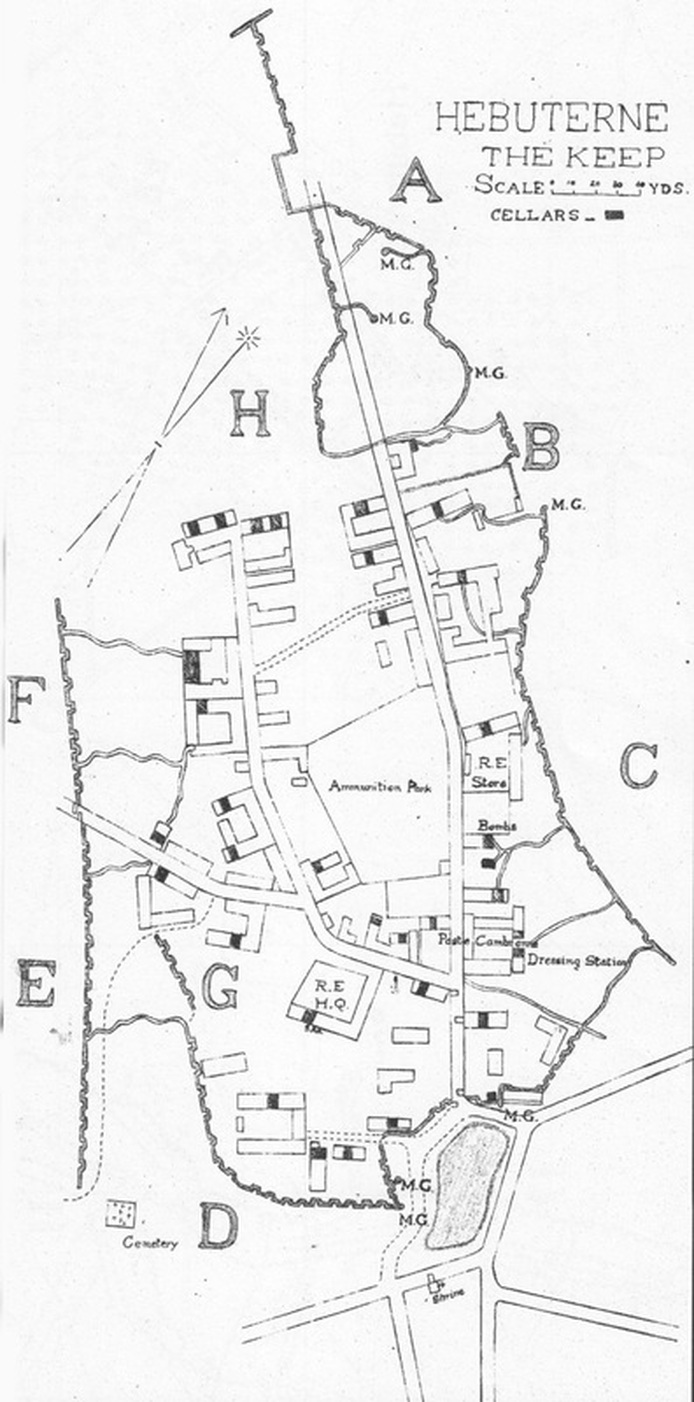

Brigade and Battalion headquarters were both in the village, and for some time occupied quarters above ground, though they were compelled eventually, when the shelling of the village became more frequent, to take to cellars and dugouts.

Company cookers were housed in the village, and from them all food was carried up to the front line through communication trenches.

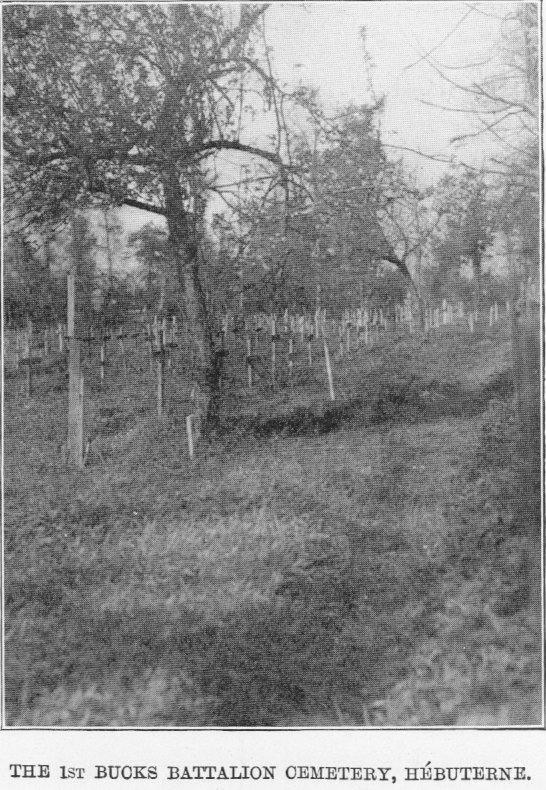

The Battalion in Brigade reserve occupied billets above ground in Hebuterne, and of this one company was detailed as garrison of a large portion of the village defences, in case of attack. This company had considerably the best of the billets, living in what was known as the “keep,”a really charming spot amongst orchards and trees.

When the battalion first arrived at Hebuterne the sector was fairly quiet, there being a tacit agreement, with the Germans opposite, that provided they would leave Hebuterne quiet, we would not entirely destroy Gommecourt, and again, if they decided to leave Sailly alone, we in our turn would keep our hands off Bucquoy and Puisieux. What actually occurred was a gradual warming up of artillery fire on the villages by both sides, and it became just as gradually evident that life above ground was not only unwise, but exceedingly foolish, with the result that, after several months’ work, dugouts had been constructed for the entire garrison of Hebuterne.

During the first six weeks, reliefs of this sector of the front line, by the 5th

Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment and the battalion, took place every

eight days.

Throughout the six months during which the Battalion held K sector, patrolling was most active; this was very necessary to prevent the enemy establishing control of the extensive “No Man’s Lands’ which lay between us. With the exception of a Z-shaped hedge, known as the Z hedge, which lay out in front of the left company, “No Man’s Land” was very featureless. This hedge, however, provided no end of excitement, for it was most difficult at night for either side to locate and dislodge a party which had got out first and taken up a position in it. But the enemy were seldom, if ever, permitted to do this owing to the battalions constant patrolling, and after some months they gave up all except periodical visits.

About September, the 5th Gloucesters took over the trenches on the right, and from then onwards to December were relieved by the 6th Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment (144th Infantry Brigade) every eight days.

Each Battalion on relief went back some four miles to the village of Couin.

On the way back to these billets from the trenches during the evening of January 27, 1916, the Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel C. P. Doig, D.S.O., sustained severe injuries through a fall from his horse, and Major L. C. Hawkins assumed command.

In January the Command of the 145 Brigade was taken over by Brigadier-General H. R. Done.

Towards the middle of the month the Battalion had to bid good-bye to K sector. It had done so much work on it in the way of defence and comfort that the order came as a bitter blow, the more so as the trenches they were to take over were in the last state of decay and were rapidly falling in everywhere. They lay more to the S.E. of Hebuterne, in very much lower ground than K sector.

They were warned that a bad state of affairs existed in this, G sector, and were told that the Battalion had been singled out for bettering it. The result was that every man was out to do his utmost with the spade and show some substantial improvement, and it was not long before a very marked change had been effected, and life was made a little more possible. Efforts to keep open the communication trenches Jena, Jean-Bart and Vercingetorix were positively heart-rending, and the results achieved, even in good weather, were in no way proportionate to the amount of work put on to

them.

In addition, the enemy artillery became daily more active, and their shooting, which was most exceptionally good, accounted for quite a number of casualties.

During the period that the Battalion held G sector, the enemy undertook several raids, though on no occasion did he succeed in entering the Battalion’s trenches. All these raids were preceded by extremely heavy bombardments, usually of about an hour’s duration.

In all these bombardments our trenches invariably suffered considerably, the more so when Minenwerfers were employed in large numbers, as these shells made the most gigantic craters, which completely obliterated all traces of dugouts and trench.

At the beginning of April 1916 the Battalion was relieved in G sector, and took over trenches between G and K sectors. These were better but by no means good.

Fighting patrols, with the coming of better weather, were now sent out more frequently, and brisk fighting in “No Man’s Land " resulted.

In May 1916, the Battalion was withdrawn from the front area, and sent back to rest at Beauval, where a fortnight was spent before moving to Agenvillers for a week. The most strenuous training was undertaken at these two places, and all manner of attacks practised, with a view to the coming British offensive.

During the march from Beauval to Agenvillers on June 2, the Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel L. C. Hawkins, was unfortunate enough to meet with a similar accident to that which befell Lieutenant-Colonel Doig, being thrown from his horse and seriously damaging his shoulder. Major L. L. C. Reynolds then assumed command, Captain A. B. Lloyd-Baker being appointed second in command.

On June 9, the battalion moved back to the line, and held the Hebuterne trenches during the preparations for the coming big offensive. But for these operations it had been decreed that the 48th Division was to be in VII. Corps reserve, with the result that zero day (July 1, 1916) found the battalion no nearer to the line than Couin Woods.

The casualties for this period were:

OFFICERS

Killed: 2

Wounded: 3

OTHER RANKS

Killed: 15.

Wounded: 156.

Missing: 1.

HEBUTERNE

June 1915 to June 1916

BASED ON EXTRACTS FROM CITIZEN SOLDIERS OF BUCKS BY JC SWANN AND THE FIRST BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BATTALION 1914-1919 BY PL WRIGHT

Shortly before the Battalion moved from Ploegsteert Major-General Heath was compelled by ill-health to vacate the Command of the 48th Division, and Major-General R. Fanshawe, C.B., D.S.O. (52nd Light Infantry) was appointed to succeed him.

There followed a series of three night marches, via Vieux-Berquin, Merville,

Busnettes, to Allouagne, which lies five miles west of Bethune

The billets at Allouagne were the best the battalion had seen, and a happy fortnight was spent here. Training was strenuous and carried out mostly in a neighbouring wood, called the Bois de Maraquet.

On the 12th July, the Battalion was moved in to bivouacs close to Noeux-les-Mines, every man available during the two succeeding days being put on to digging a new rear line. It was thought that the Division was to take over new trenches in this area but on July 16 the battalion suddenly got orders to move, and marched the whole of that night, in a deluge of rain, to billets in Lieres, passing within a stone’s throw of Allouagne.

On the 18th the battalion were put into a train at Berguette, which slowly

proceeded to Doullens. A two hours’ march from there took the battalion to some woods at Marieux, where it arrived at 4 a.m. to bivouac.

On July 20, the 48th Division started to relieve the French in the line in front of the village of Hebuterne, the Bucks Battalion being in reserve, with two companies at Sailly-au-Bois and two companies at Bayencourt. Both these villages were then a mass of flies, owing to the general filth everywhere, and, as the weather was extremely hot, life in these billets was none too pleasant.

The trenches, which the Battalion took over on July 24, lay some 100 to 300 yards east of Hebuterne and were at this time good and quiet. Unlike the front line at Ploegsteert, where the trenches consisted of sandbagged barricades, these trenches were dug down about 6 feet deep all along.

The enemy’s trenches were from 300 to 1,000 yards distant, instead of being within 100 to 200 yards as at Ploegsteert. For about a fortnight the Division was supported by French guns, with apparently no shortage of ammunition. They were always able to send back three times as many shells as the enemy had given to our front trenches, and they were much missed by the Infantry when they were relieved by our own artillery, still bound to economy in the matter of ammunition.

The dugouts had the outward appearance of real luxury, owing to a large portion of the furniture of Hebuterne having been imported into them. Four-poster beds existed in quite a number, but owing to the quantities of small vermin and mice which had made their homes in them, they proved to be most undesirable, and were almost all scrapped before the battalion had been a week in the line.

Brigade and Battalion headquarters were both in the village, and for some time occupied quarters above ground, though they were compelled eventually, when the shelling of the village became more frequent, to take to cellars and dugouts.

Company cookers were housed in the village, and from them all food was carried up to the front line through communication trenches.

The Battalion in Brigade reserve occupied billets above ground in Hebuterne, and of this one company was detailed as garrison of a large portion of the village defences, in case of attack. This company had considerably the best of the billets, living in what was known as the “keep,”a really charming spot amongst orchards and trees.

When the battalion first arrived at Hebuterne the sector was fairly quiet, there being a tacit agreement, with the Germans opposite, that provided they would leave Hebuterne quiet, we would not entirely destroy Gommecourt, and again, if they decided to leave Sailly alone, we in our turn would keep our hands off Bucquoy and Puisieux. What actually occurred was a gradual warming up of artillery fire on the villages by both sides, and it became just as gradually evident that life above ground was not only unwise, but exceedingly foolish, with the result that, after several months’ work, dugouts had been constructed for the entire garrison of Hebuterne.

During the first six weeks, reliefs of this sector of the front line, by the 5th

Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment and the battalion, took place every

eight days.

Throughout the six months during which the Battalion held K sector, patrolling was most active; this was very necessary to prevent the enemy establishing control of the extensive “No Man’s Lands’ which lay between us. With the exception of a Z-shaped hedge, known as the Z hedge, which lay out in front of the left company, “No Man’s Land” was very featureless. This hedge, however, provided no end of excitement, for it was most difficult at night for either side to locate and dislodge a party which had got out first and taken up a position in it. But the enemy were seldom, if ever, permitted to do this owing to the battalions constant patrolling, and after some months they gave up all except periodical visits.

About September, the 5th Gloucesters took over the trenches on the right, and from then onwards to December were relieved by the 6th Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment (144th Infantry Brigade) every eight days.

Each Battalion on relief went back some four miles to the village of Couin.

On the way back to these billets from the trenches during the evening of January 27, 1916, the Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel C. P. Doig, D.S.O., sustained severe injuries through a fall from his horse, and Major L. C. Hawkins assumed command.

In January the Command of the 145 Brigade was taken over by Brigadier-General H. R. Done.

Towards the middle of the month the Battalion had to bid good-bye to K sector. It had done so much work on it in the way of defence and comfort that the order came as a bitter blow, the more so as the trenches they were to take over were in the last state of decay and were rapidly falling in everywhere. They lay more to the S.E. of Hebuterne, in very much lower ground than K sector.

They were warned that a bad state of affairs existed in this, G sector, and were told that the Battalion had been singled out for bettering it. The result was that every man was out to do his utmost with the spade and show some substantial improvement, and it was not long before a very marked change had been effected, and life was made a little more possible. Efforts to keep open the communication trenches Jena, Jean-Bart and Vercingetorix were positively heart-rending, and the results achieved, even in good weather, were in no way proportionate to the amount of work put on to

them.

In addition, the enemy artillery became daily more active, and their shooting, which was most exceptionally good, accounted for quite a number of casualties.

During the period that the Battalion held G sector, the enemy undertook several raids, though on no occasion did he succeed in entering the Battalion’s trenches. All these raids were preceded by extremely heavy bombardments, usually of about an hour’s duration.

In all these bombardments our trenches invariably suffered considerably, the more so when Minenwerfers were employed in large numbers, as these shells made the most gigantic craters, which completely obliterated all traces of dugouts and trench.

At the beginning of April 1916 the Battalion was relieved in G sector, and took over trenches between G and K sectors. These were better but by no means good.

Fighting patrols, with the coming of better weather, were now sent out more frequently, and brisk fighting in “No Man’s Land " resulted.

In May 1916, the Battalion was withdrawn from the front area, and sent back to rest at Beauval, where a fortnight was spent before moving to Agenvillers for a week. The most strenuous training was undertaken at these two places, and all manner of attacks practised, with a view to the coming British offensive.

During the march from Beauval to Agenvillers on June 2, the Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel L. C. Hawkins, was unfortunate enough to meet with a similar accident to that which befell Lieutenant-Colonel Doig, being thrown from his horse and seriously damaging his shoulder. Major L. L. C. Reynolds then assumed command, Captain A. B. Lloyd-Baker being appointed second in command.

On June 9, the battalion moved back to the line, and held the Hebuterne trenches during the preparations for the coming big offensive. But for these operations it had been decreed that the 48th Division was to be in VII. Corps reserve, with the result that zero day (July 1, 1916) found the battalion no nearer to the line than Couin Woods.

The casualties for this period were:

OFFICERS

Killed: 2

Wounded: 3

OTHER RANKS

Killed: 15.

Wounded: 156.

Missing: 1.

Proudly powered by Weebly