- HOME

- SOLDIER RESEARCH

- WOLVERTONS AMATEUR MILITARY TRADITION

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE RIFLE VOLUNTEERS 1859-1908

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BATTALION 1908-1947

- The Bucks Battalion A Brief History

- REGIMENTAL MARCH

-

1ST BUCKS 1914-1919

>

- 1914-15 1/1ST BUCKS MOBILISATION

- 1915 1/1ST BUCKS PLOEGSTEERT

- 1915-16 1/1st BUCKS HEBUTERNE

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS SOMME JULY 1916

- 1916 1/1st BUCKS POZIERES WAR DIARY 17-25 JULY

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS SOMME AUGUST 1916

- 1916 1/1ST BUCKS LE SARS TO CAPPY

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS THE GERMAN RETIREMENT

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS TOMBOIS FARM

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS THE HINDENBURG LINE

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS 3RD BATTLE OF YPRES

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES 16th AUGUST

- 1917 1/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES WAR DIARY 15-17 JULY

- 1917 1/1ST BUCKS 3RD BATTLE OF YPRES - VIMY

- 1917-18 1/1ST BUCKS ITALY

-

2ND BUCKS 1914-1918

>

- 1914-1916 2ND BUCKS FORMATION & TRAINING

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS ARRIVAL IN FRANCE

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS FROMELLES

- 1916 2/1st BUCKS REORGANISATION

- 1916-1917 2/1st BUCKS THE SOMME

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS THE GERMAN RETIREMENT

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS ST QUENTIN APRIL TO AUGUST 1917

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS 3RD YPRES

- 1917 2/1st BUCKS ARRAS & CAMBRAI

- 1918 2/1st BUCKS ST QUENTIN TO DISBANDMENT

-

1ST BUCKS 1939-1945

>

- 1939-1940 1BUCKS MOBILISATION & NEWBURY

- 1940 1BUCKS FRANCE & BELGIUM

- 1940 1BUCKS HAZEBROUCK

- HAZEBROUCK BATTLEFIELD VISIT

- 1940-1942 1BUCKS

- 1943-1944 1BUCKS PREPARING FOR D DAY

- COMPOSITION & ROLE OF BEACH GROUP

- BROAD OUTLINE OF OPERATION OVERLORD

- 1944 1ST BUCKS NORMANDY D DAY

- 1944 1BUCKS 1944 NORMANDY TO BRUSSELS (LOC)

- Sword Beach Gallery

- 1945 1BUCKS 1945 FEBRUARY-JUNE T FORCE 1st (CDN) ARMY

- 1945 1BUCKS 1945 FEBRUARY-JUNE T FORCE 2ND BRITISH ARMY

- 1945 1BUCKS JUNE 1945 TO AUGUST 1946

- BUCKS BATTALION BADGES

- BUCKS BATTALION SHOULDER TITLES 1908-1946

- 1939-1945 BUCKS BATTALION DRESS >

- ROYAL BUCKS KINGS OWN MILITIA

- BUCKINGHAMSHIRE'S LINE REGIMENTS

- ROYAL GREEN JACKETS

- OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1965

- OXF & BUCKS LI INSIGNIA >

- REGIMENTAL CUSTOMS & TRADITIONS >

- REGIMENTAL COLLECT AND PRAYER

- OXF & BUCKS LI REGIMENTAL MARCHES

- REGIMENTAL DRILL >

-

REGIMENTAL DRESS

>

- REGIMENTAL UNIFORM 1741-1896

- REGIMENTAL UNIFORM 1741-1914

- 1894 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1897 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1900 DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1931 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1939-1945 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1950 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS

- 1960 OFFICERS DRESS REGULATIONS (TA)

- 1960 REGIMENTAL MESS DRESS

- 1963 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- 1958-1969 REGIMENTAL DRESS

- HEADDRESS >

- REGIMENTAL CREST

- BATTLE HONOURS

- REGIMENTAL COLOURS >

- BRIEF HISTORY

- REGIMENTAL CHAPEL, OXFORD >

-

THE GREAT WAR 1914-1918

>

- REGIMENTAL BATTLE HONOURS 1914-1919

- OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY INTRODUCTION

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919 SUMMARY

- 1/4 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 2/4 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 1/1 BUCKS BATTALION 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 2/1 BUCKS BATTALION 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 5 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 6 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 7 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 8 (SERVICE) OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1918 SUMMARY

- 1st GREEN JACKETS (43rd & 52nd) 1958-1965

- 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND) 1958-1965

- 1959 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1959 REGIMENTAL MARCH IN OXFORD

- 1959 DEMONSTRATION BATTALION

- 1960 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1961 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1961 THE LONGEST DAY

- 1962 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1963 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1963 CONVERSION TO “RIFLE” REGIMENT

- 1964 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1965 1ST GREEN JACKETS (43RD & 52ND)

- 1965 FORMATION OF ROYAL GREEN JACKETS

- REGULAR BATTALIONS 1741-1958

-

1st BATTALION (43rd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

-

43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1914

>

- 43rd REGIMENT 1741-1802

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1803-1805

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1806-1809

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1809-1810

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1810-1812

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1812-1814

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1814-1818

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1818-1854

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1854-1863

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1863-1865

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1865-1897

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1899-1902

- 43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1902-1914

-

1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919

>

-

1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1920-1939

>

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1920

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1921

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1922

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1923

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1924

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1925

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1926

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1927

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1928

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1929

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1930

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1931

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1932

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1933

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1934

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1935

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1936

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1937

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1938

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1939

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945 >

-

1 OXF & BUCKS 1946-1958

>

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1946

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1947

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1948

- 1948 FREEDOM PARADES

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1949

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1950

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1951

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1952

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1953

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1954

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1955

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1956

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1957

- 1 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1958

-

43rd LIGHT INFANTRY 1741-1914

>

-

2nd BATTALION (52nd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

- 52nd LIGHT INFANTRY 1755-1881 >

- 2 OXF LI 1881-1907

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1908-1914

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1914-1919

>

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919-1939

>

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1919

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1920

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1921

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1922

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1923

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1924

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1925

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1926

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1927

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1928

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1929

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1930

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1931

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1932

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1933

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1934

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1935

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1936

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1937

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1938

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI - 1939

-

2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945

>

- 1939-1941

- 1941-1943 AIRBORNE INFANTRY

- 1944 PREPARATION FOR D DAY

- 1944 PEGASUS BRIDGE-COUP DE MAIN

- Pegasus Bridge Gallery

- Horsa Bridge Gallery

- COUP DE MAIN NOMINAL ROLL

- MAJOR HOWARDS ORDERS

- 1944 JUNE 6

- D DAY ORDERS

- 1944 JUNE 7-13 ESCOVILLE & HEROUVILETTE

- Escoville & Herouvillette Gallery

- 1944 JUNE 13-AUGUST 16 HOLDING THE BRIDGEHEAD

- 1944 AUGUST 17-31 "PADDLE" TO THE SEINE

- "Paddle To The Seine" Gallery

- 1944 SEPTEMBER ARNHEM

- OPERATION PEGASUS 1

- 1944/45 ARDENNES

- 1945 RHINE CROSSING

- OPERATION VARSITY - ORDERS

- OPERATION VARSITY BATTLEFIELD VISIT

- 1945 MARCH-JUNE

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI DRESS 1940-1945 >

- 2 OXF & BUCKS LI 1946-1947 >

-

1st BATTALION (43rd LIGHT INFANTRY)

>

- MILITIA BATTALIONS

- TERRITORIAL BATTALIONS

- WAR RAISED/SERVICE BATTALIONS 1914-18 & 1939-45

-

5th, 6th, 7th & 8th (SERVICE) 1914-1918

>

-

6th & 7th Bns OXF & BUCKS LI 1939-1945

>

- 6th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI 1940-1945 >

-

7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI 1940-1945

>

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1940-JULY 1942

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JULY 1942 – JUNE 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JULY 1943–OCTOBER 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI OCTOBER 1943–DECEMBER 1943

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI DECEMBER 1943-JUNE 1944

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JANUARY 1944-JUNE 1944

- 7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1944–JANUARY 1945

-

5th, 6th, 7th & 8th (SERVICE) 1914-1918

>

- "IN MY OWN WORDS"

- CREDITS

1915-1916 THE SIEGE AT KUT-AL-AMARA

EXTRACTED FROM THE REGIMENTAL CHRONICLES OF THE OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY

EXTRACTED FROM THE REGIMENTAL CHRONICLES OF THE OXFORDSHIRE & BUCKINGHAMSHIRE LIGHT INFANTRY

Siege of Kut-el-Amara.

The Turkish prisoners taken at Ctesiphon, as well as our wounded, had been evacuated to Basra, and on the 5th December the Cavalry Brigade and the transport animals were sent down to Ali-al-Gharbi. Aware that he could expect no relief until fresh troops should arrive from overseas, and aware also that the Turks, in increased numbers, were hemming him in, Townshend prepared to stand a siege. The place had practically no defences, for although during the absence of the 6th Division up river a scheme of defence was mooted, for one reason or another little or nothing was done. There had been built a so-called fort consisting of mud walls, useless against artillery, and three or four equally useless block-houses, joined by a barbed-wire cattle fence, stretching across the neck of the river's loop. All this had to be altered, and henceforward strenuous digging went on day and night. Fortunately the enemy gave us time, for though he drew gradually nearer on the north, he did not force an attack.

By the 7th December, however, Kut was completely invested, and from that time only wireless messages told the outside world what was happening to the besieged garrison. From these it was learned that, on the 8th December, Nur-ud-Din went through the formality of calling on General Townshend to surrender; on the 9th drove in the British detached post on the right bank of the river, and then, for several days, bombarded Kut from all sides, and pushed infantry attacks against the northern defences, to be repulsed with heavy losses on each occasion. After the 12th December the enemy abandoned these costly attacks, and settled down to a bombardment and sapping operations, the particular objective being the Fort at the north-east corner of the defensive line. Between the 14th and 18th successful sorties were made by the garrison, and it was not until: the night of the 23rd/24th December that the Turks again made any strenuous effort to renew the assault.

On that night and the following day the Fort was subjected to heavy concentrated fire, with the result that the parapet was breached, and the Turks effected an entry. The success, however, was only momentary, for a counter-attack immediately ejected them, and they left behind them some 200 dead.

Not content with this rebuff, the enemy returned to the attack a little later, and at midnight (24th/25th) again entered the Fort. "The enemy," said General Townshend, in his wireless report, "effected a lodgment in the northern bastion, were ejected, came on again, and occupied the bastion. The garrison (Oxford Light Infantry and 103rd Mahrattas) held on to an entrenchment, and were reinforced by the 48th Pioneers and the Norfolk Regiment. The enemy vacated the bastion on Christmas morning, and retired into trenches from 400 to 900 yards in the rear, although the attack had been made from trenches only about 100 yards from the breach. The rest of Christmas Day passed quietly. The fort garrison, in excellent spirits, reoccupied the bastion.

The enemy's casualties estimated at about 700, our own at 190 killed and wounded."

This was the last attack made on Kut, for Nur-ud-Din, assured by the German Marshal, Yon. der Goltz, of the impossibility of the garrison breaking out, left sufficient troops to contain it, and on the 28th December commenced moving strong forces down to Sheikh Saad, in order to frustrate any attempt on the part of the British to relieve the beleaguered garrison.

During the four long months which followed the "gallant 6th Division," locked up securely, withstood with patience and resolution all the rigours of a siege— wondering often if the floods would prove a greater enemy than the Turks, yet hoping always that relief would come at any moment. Time after time were they disappointed, for the Turks, reinforced frequently, beat back every attempt of the relieving force to hew its way through, until at the end of April 1916 Kut was starved into surrender, and the 6th Division made prisoners of war.

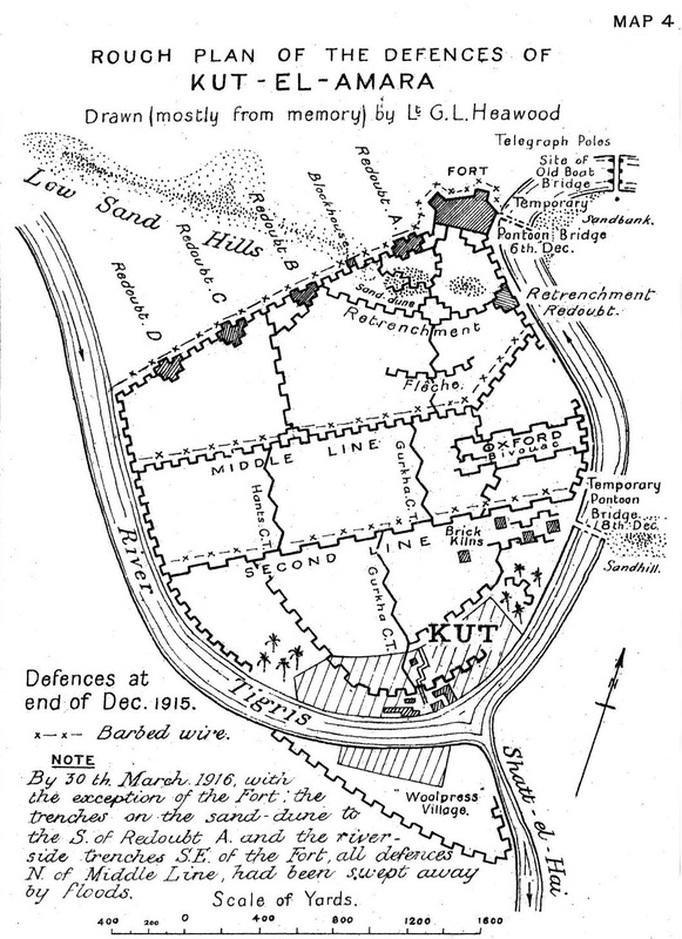

The following description of the retirement from Ctesiphon and the Siege of Kut-el-Amara was written in 1916, after his exchange as a prisoner of war, by Lieut. G. L. Heawood, 2/4th Wiltshire Regiment, who was attached to the 1st Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, and commanded Q Company from the 24th November 1915 until the surrender of Kut. We give his account first, because the time at which it was written down was nearest to the events recorded. The other accounts, also written from memory, were put together at somewhat later times.

Lieut. Heawood's Narrative.

On the evening of the 23rd November(Unfortunately, I was not present during the attack on the 22nd, as I was at Lajj with the boats, and could not get up to Ctesiphon until the battery wagons came down to refill.—G. L. H,) the British force bivouacked at a spot about the centre of what had been the Turkish first line. The spot was called High Wall, from the fact that there was a high and thick wall there forming three sides of a square, which the Turks had improved into a redoubt. Within the redoubt I remember seeing a very ancient mortar, on which there were some curious figures and letters. Ctesiphon Arch stood out about a mile away, and, with its surroundings, presented a most picturesque scene.

The Turks had retired for at least two miles, but there were still Arab horsemen about, and these began to hover around us as dusk came on. All that night and the following day our wounded (of which there were immense numbers) were collected and evacuated to Lajj, our base camp by the river, some eleven miles in rear.

Early on the morning of the 25th there was some slight trouble with Arabs, but a few shells from our guns dispersed them, and for the rest of the day we settled down to digging additional trenches. From the top of the High Wall one obtained a good view of the country to the north, and during the afternoon we could see in the distance large Turkish forces moving away towards the east. So far we subordinates knew nothing of the plans for the future, but at 6 p.m. orders were issued for a move in an hour's time, and all available carts with the force were redistributed to units. Anything that could not be taken with us was to be buried or destroyed, and the usual night-march regulations were to be stringently enforced—absolute silence, and no lights. By 7 p.m. we were on the move, and after some delay in getting units into their proper order of march, we settled down to our trek back to Lajj, where we eventually arrived at about midnight. Then followed the wearisome process of telling off the troops to their respective bivouacs, which Avas no easy matter in the dark, and was made worse by a heavy downpour of rain. Happily the cooks, who had marched ahead, had tea ready for us, and, better still, the blankets had not been unpacked before the rain came on, .so only the outer ones were wet. Warm tea and warm blankets helped us a lot. The Regiment bivouacked for the night about the north-east corner of the camp, but it was well on into the early hours of the morning before we had settled down and posted sentries on our part of the perimeter.

The 26th was spent in what seemed to us rather an aimless sort of way. Schemes for outposts were being got out; boats of wounded sent down the river; our cavalry out keeping touch with the enemy cavalry; but no one quite knew what was going to be done next. Late in the afternoon we took up a line of outposts, my company furnishing three piquets, so we had little rest that night. Next morning, however, we were relieved, and the cavalry and small day-groups of infantry kept a look-out. At midday (27th) we received our orders to march, and the advance parties got off about 2 p.m. We qurselves were among the last to move, and did not clear the camp until quite near dusk. Our cavalry still remained away on our flank and rear, and aeroplanes had been on the move up to the last moment; moreover, to further induce the Turks to believe that we were staying at Lajj, a considerable number of tents were left standing. The nighfs march' was a particularly dreary one, although, as matters turned out, it proved quite successful. Many things contributed to make it dreary : we had not been told how far it was proposed to go; we did not know what excitements there might be in store for us on the way; it was a densely dark night, the wind was getting up, and the clouds of the rainy season gathering round; halts were somewhat frequent; and once or twice we were sniped at by Arabs, in spite of our flank guards. When at last day broke, matters became pleasanter, and at about 8 a.m. (28th) we approached Aziziyeh, where we had spent a month in camp on our way up to Ctesiphon. General Townshend and his Staff stood at the entrance to the camp, and saw every regiment march in, and by 9 a.m. we had settled down in bivouac, and were glad of breakfast. We must have covered a very good 25 miles since leaving Lajj, and the fatigue of the march was immensely increased by the slow pace and the many unavoidable halts.

Most of that day and the following night we rested, and the 29th was spent chiefly in refitting the men and trying to evacuate stores from Aziziyeh. Much stuff had, of course, to be abandoned, as most of the boats had gone down-stream with wounded; but a certain amount was floated down the river, while things that could not be saved were destroyed.

On the morning of the 30th we made a very early start, all arrangements having been made the day before. Apparently there was an impression that we were becoming tolerably safe from a close pursuit; also, what with the fighting at Ctesiphon and the long night march to Aziziyeh, everyone was more or less tired out. Whether these were the reasons or not, I cannot say ; but we were given a march of only 8 miles or so, and went into bivouac on the river bank, about a mile beyond some mounds marked on our map as Um-al-Tumman (Umm-ath-Thumma), which soon after came to be known as "Ummle-Tummle," and, finally, as "Rumble-Tumble," but all this was after it had become identified with the most adventurous part of the retirement. Soon after we got in we started digging trenches round the camp, and others in the camp for shelter, and by nightfall everything was looking fairly bright. Ample food had been brought with us from Aziziyeh, and I remember that at "drumming-lip" that evening my company had any amount of bacon frying. There was also plenty of straw and hay close to our lines, which were in part of a deserted Arab village; so we had soft beds. Besides all this, we had received reinforcements before leaving Aziziyeh—half a battalion of the West Kents and the 14th Hussars, freshly arrived in the country—a welcome addition to the Indian Cavalry. So far there was every promise of our getting down to Kut by easy stages, but it was not to be, for just as we were settling down to a comfortable night, we heard the boom of a gun, and presently the distant rattle of musketry, followed by the bursting of a shell, evidently fired in our direction. This was the end of our comfortable night, for we were ordered into the trenches forthwith, and though nothing particular happened, spasmodic shelling went on throughout the night. Instead of getting away next day, we had to remain, as some of the steamers had run aground, and the enemy was reported to be coming down the banks in force.

Almost before daylight on the 1st December the transport moved out of camp towards the south. The 17th Brigade had been told off as rearguard, and I found myself extending my company out along the northern part of the camp, and watching masses of our cavalry moving away eastward into the desert in the grey light of early morning. The column was barely clear of the camp before it became evident that we were going to be attacked; bullets began to fall, but not very well aimed, although, as a matter of fact, a man of my company was wounded.

After a while things became more lively, and we fell back a little on to our two support companies, who were lining a magnificent nullah about 100 yards behind us. The companies of the other regiments fell back also, and soon the whole of the 43rd were extended along this nullah, covering the retirement of the other units. Meanwhile, our artillery was doing good work in keeping the enemy back, and we remained in position until his skirmishers had come within a few hundred yards, when we withdrew through the 22nd Punjabis, who were lined out ready to cover our withdrawal to another nullah 120 yards or so behind. These alternate retirements continued for some distance across some very open desert,,the 22nd Punjabis, with whom we worked all through, behaving splendidly. The other two regiments on our right retired in a similar: manner, and, with each retirement, we gradually increased the distance between ourselves and the Turks. The enemy's shrapnel fire! was rather trying, as it burst very accurately; but;we were remarkably fortunate in casualties, having very few, and being able to get nearly all the wounded back to the field ambulance.

After crossing the open stretch of desert we rejoined our guns, and held on while they limbered up and got away to a fresh position in rear. This manoeuvre—first the guns retiring and then ourselves —went on for some little time, and, whenever we had to wait for the guns to get back, the Turks pushed in closer, though we left them behind again whenever we retired. At last we so increased the distance, that it became safe for us to retire in artillery formation, but even then we had occasionally to form a firing line in a nullah. So the day went on, and we were beginning to think that there would be no end to it, when, much to our relief, we were reinforced by the 30th Brigade, who had been sent on two nights before in advance of the main body to Kut, but had been ordered back when the trouble began. They now co-operated with our Brigade, and before very long we reached a bend in the river, where we halted for about half an hour, while our wounded were put on a boat and sent off.

Meanwhile, much had been going on on the river itself, though, of course, unknown to us, fighting our way across country. It appears that the boats remjaining at Aziziyeh, in order to accompany us down stream, weighed anchor at daylight. They could not start earlier, owing to the particularly bad sand-banks which infest the reach of the river hereabouts, making rapid progress even by day quite out of the question. As it was, we lost at least two barges here—one an aeroplane barge, and the other an ordnance one. On the latter, most unfortunately for us, were all our regimental orderly-room papers and documents—a most serious loss, which produced endless work after reaching Kut, as all company papers had gone, including pay-sheets, nominal-rolls, etc. The two gunboats seem to have hung on too long, and the "Firefly" was knocked out by a shell through her boiler, after her commander had been wounded. The "Comet" stood by to help her, and took off her crew, but almost immediately ran aground, and soon shared the fate of the "Firefly," though not before the wounded had been transferred to a barge and towed away by a small tug. The crews got ashore and eventually joined our column,-amongst them being Colour-Sergeant H. Gibbs, the Machine-gun Sergeant of the "Firefly," who had been lent from the Regiment for this duty, and who afterwards became C.-Q.-M.-S. of Q Company.

However, to return to the river-bend at which we had halted. It was obviously not a spot at which to make a long stay, much as we desired a good rest, and soon we were on the road again, the 17th Brigade still in rear, though now more or less closed up, as our cavalry were protecting our flanks and rear. The track now lay inland across the desert, which, except for scattered low scrub bushes, was bare and dry. All the regimental horses (even the Colonel's) had been sent on with the transport, so everyone had to foot it. Occasionally a transport-cart, or one of the three motorcars which were in the country, turned back to pick up stragglers; for, as the day advanced, it became more and more difficult to keep the men going, in spite of their knowledge that if they dropped out they would have a short shrift from the merciless Arabs. I think that the poor little Gurkhas (belonging to the 30th Brigade) suffered most, as they are not built for forced marching, and they had had more than their share since they had been turned back to help us in the morning. Still, I may say here that they stuck it heroically, and the 30th Brigade lost not a single man taken prisoner all the way back to Kut.

Later, we were encouraged by the announcement that, after seven more miles, we should halt on the river bank, get water, and rest for three hours. Our spirits revived, and, after a rather weary drag, we found ourselves close in to the river again, near a clump of trees. Mules were off-loaded, water-drawers detailed, and equipment loosened. But fate was against us once more. Before the water-parties had reached the stream there was a rattle of musketry, and, though the offenders were only Arabs, our machine-guns were unable to suppress the firing. Our prospect of water and a rest had vanished, and within half an hour we were off again, on another slow night march. The night was black, and it was impossible to see men at any distance in front of one; consequently the pace averaged barely two miles an hour. Obstacles, such as dry nullahs or clumps of low scrub, constantly caused checks to the column, and it was no easy matter to keep even one's company closed up, especially as the men were more or less done up and only half awake. In this way we plodded slowly on until, at about 2 a.m. (2nd December), we saw bivouac fires ahead, and were told that we might lie down, as we were, in column of route. Food was not forthcoming, as the transport was a long way ahead; water, we were promised we should get soon after we started again. It was a bitter night, with a strong north wind, and our cotton uniform did not help us to keep out the cold. Three of us tried to make a fire, but it would not burn, so we gave up the idea, and sat round and dozed—but not for long, for soon the order came to be ready to move in five minutes. The mules were loaded up, and we were off again.

Soon after starting we passed over a brick bridge which spanned a large dry watercourse, and this the sappers blew up as soon as the column was; clear, thereby creating a considerable obstacle to the immediate passage of enemy guns. We now moved across the desert in parallel columns of companies, with the cavalry covering our inland flank and our rear. For breakfast the men were allowed to eat their emergency rations, but the promise of water remained only a promise. It grew harder and harder to keep the men going, as they were quite ready to fall out, and prepared to risk everything for a rest and a drink of water; but the N.C.O.'s were magnificent, and it was due to them that we managed to get along. Twice we approached the river and had to go on, but at last we actually halted at a watering-place, and the water-parties got down to the river bank. Even then it was questionable whether we should get our drink, as Arabs began sniping from the opposite bank. Oar machine-guns were soon at work, however, sweeping all visible ground, and the 18-pounders unlimbered and gave them a few well directed shells — things which the Arab dislikes intensely,

We had a rest of nearly three hours, and the men had time to "drum-up," i.e., make cocoa and boil up their emergency rations in their mess-tins. When we got under way again, we had about 9 miles to go to reach the outskirts of Kut, but dusk came on before we saw any signs of the place. The cavalry were drawn in, and we put out flank guards; then carts came out, some to pick up the most footsore of the tired men, and others with food—a somewhat scanty allowance, but most welcome. We waited for some time, and wondered why, until we learned that we would not enter the place until daylight, when we could go right in, and take up our allotted quarters without any trouble.

Quite early next morning (3rd December) we covered the last two miles, and, marching straight to our camping-ground, had a good hot breakfast, rolled ourselves up in our blankets, and slept until midday.

Of the next few weeks the chief memory that remains is one of digging. We seem to have dug all day and every day—in the glare of the sun, in the darkness of the night, and in the moonlight. We commenced these labours on our first afternoon, for although we were not technically surrounded for another three or four days, we prepared for the siege which was known to be inevitable. The ships with our wounded and the Turkish prisoners were all sent away down river, only the "Sumana," with one or two tugs and the 4.7-inch gun barges, remaining at Kut. Then the cavalry (less one squadron) were dispatched down to Ali-al-Gharbi, and on the 7th December we were invested. "I will now give a description of Kut and the defences when the siege commenced.

The town lies at the apex or toe of a horse-shoe bend of the river, and contains some very respectable buildings, including -a covered-in bazaar, a caravanserai, the Sheikh's house, two mosques (one with a fine minaret), and other large public and private buildings. These are all built of hard, mud bricks, have several stories, and generally a courtyard in the centre, with much woodwork, some of it, quaintly carved. There are palm gardens scattered about the town, and large palm groves at either end, while on the outskirts to the north-east are some old brick-kilns, solidly built, in the shape of small, squat towers, with broad and hollow bases' These eventually were much used by the artillery. Opposite the town and on the other side of the Tigris, the Shatt-el-Hai flows out southwards to the Euphrates, though it dries up in the summer South-west of Kut, and in the angle formed by the Tigris and the Hai, stands a small village (whose name I never saw in writing, but pronounced something like Woolpress), close to which was an old liquorice factory, with some liquorice stacks a little farther west.

North-east of the Hai, and two or three miles down the right bank of the Tigris, is another small Arab village, with more liquorice stacks, and close by there was a Turkish bridge of boats (by means of which the telegraph wires crossed the river), which,, of course, we removed. Across the neck of the river bend (i e across the heel of the horse-shoe), a line of five block-houses with barbed wire in the intervals and a large mud fort at the north-east end, had been put up after our original advance from Kut as a protection against Arab raiders. That was all we found by way of defences when we commenced preparations for the siege. In one respect we were certainly fortunate : large stores of grain were found in and about the town, and, of course, materially lengthened the siege.

The above defence arrangements might have been all very well against Arabs, but as the block-houses had nothing more than loop-holed walls above ground-level, they were quite useless against Turks with artillery; they were demolished, and a line of strong redoubts substituted. The Fort, however, was left standing as it was so big that to get rid of it would have entailed too much work and a waste of explosives; but it was strengthened considerably with dug-outs, trenches, and overhead cover. As a matter of fact it proved very useful, though attracting a good deal of the enemy's attention.

On the 4th December General Townshend issued the following :—-

Special order. Proclamation to the Troops.

" I intend to defend Kut-al-Amarah, and not to retire any further; reinforcements are beginning to be sent up from Basra to relieve us. The honour of our Mother Country and the Empire demands that we all work heart and soul in the defence of this place. We must dig in deep, and dig in quickly, and then the enemy's shells will do little damage. We have ample food and ammunition, but Commanding Officers must husband the ammunition, and not throw it away uselessly.

"The way you have managed to retire some 80 or- 90 miles under the very noses of the Turks is nothing short of splendid, and speaks eloquently for the courage and discipline of this force."

(This Order and General Townshend's Communiques (printed further on) were copied into a notebook by an officer in Kut, who was subequently exchanged as a prisoner of war. He succeeded in bringing his notebook away with him, and, on reaching India, had type-written copies made of the entries,—-G, L. H,)

On our first afternoon the Regiment dug trenches for about four hours along the river bank between the Fort and the brick kilns. That is to say, we entrenched our bivouac ground, and that night we only found river piquets, the remainder of us sleeping in the new trenches, where we were secure from sniping from the opposite bank of the river. Next morning we completed these trenches and added some improvements; but this was not to be our permanent home, for in the evening another regiment relieved us, and we dropped back to two dry watercourses, more or less at right angles to our former trenches. This new line faced north, with its right adjoining the southern end of the previous line, and its left on the track from the town to the Fort. The 63rd Battery R.F.A. dug themselves in on our left.

During the early part of this night we improved and made habitable these two parallel watercourses, and subsequently we improved them still further, as they became our headquarters until the end of the siege. In the front line there were three companies, R on the left, P on the right, and Q in the centre, while S Company was in the rear watercourse, or trench, behind Q and P Companies. The trenches were eventually roofed over, as were also the various dug-outs (between the two lines of trenches), such as the mess, dressing-station, orderly-room, quartermaster's stores, men's cookhouse, Company Officers' quarters, etc. Nominally, this was our bivouac ground, and it was the place to which we always came back, though we really seldom occupied it, as we were generally digging, or working, or holding trenches elsewhere. At this time the nights were very cold: bitter north-west winds, with an occasional frost; and the days also were quite chilly. .

The next bit of work we commenced was a communication trench to the Fort, while other regiments dug trenches along the barbed wire on the old block-house line. But that was before we were cut off from the outside world. From the 7th December business began in earnest; most movements above ground had to be done at the double, and all digging was got down a rough three feet by night, earth being thrown up on whichever side seemed most exposed, and then completed by day. The Turks started in by drenching the place with shells; I do not know how many hundred they fired at us in these early days; and a little later, when they got closer, they swept all the flat ground with machine-gun fire.

I think it was on the night of the 7th/8th that the enemy made his first attack—in actual fact more like a reconnaissance in force. He made for the Fort and adjacent trenches, and three of our companies went up and manned the trenches which we had originally dug from the Fort southwards along the river. A few men of the Regiment were wounded, but the attack soon dwindled, and we returned to our bivouac quite early in the night. It must have been the next day or the day after that an attempt was made, before the Turks closed in on the east, to establish a bridgehead post on the right bank of the river opposite the brick-kilns. The bridge of boats was towed to this point in the early morning, and a small force (from the 30th Brigade) was put across, while we assisted by lining the river bank just south-east of our bivouac. The attempt, however, was a failure owing to the resistance offered and the fire which the Turks kept up on the bridge. The withdrawal of the party was effected, and the bridge was partly recovered and partly demolished. After this the only post which we had on the right bank of the river was round the place which I write "Woolpress " in trenches across the angle between the Hai and the Tigris.

From this time onwards the Turks were continually advancing and making preliminary attacks on our northern front, while we used to man our trenches, generally for 48 hours in and 24 hours out, though the latter period was usually harder than the former, as it was mainly spent in digging communication trenches and making our portion of the inner defences, or what was known as "Middle Line." The Turks made no actual assault during these early weeks, but they drew closer in, and we had some very anxious nights, especially on one occasion when we got a regular alarm of a night attack and the artillery fired star shells, etc., for some time. During the daytime they occupied themselves with shelling our various defences and the town, sweeping our trenches repeatedly with machine-gun fire, and sniping with the greatest accuracy. It was, I think, on December 11th that poor Brown, who commanded P Company, was killed by a sniper's bullet in the head, and we lost several men in a similar way—happily, all quite instantaneous. But in the very narrowed circle within which we were living, losses like these were felt deeply, and Brown had always been the most lively member of the mess. We suffered also from shrapnel, for the enemy, being all round us, was able to fire into our rear from across the river.

Throughout December (and, indeed, almost up to the bitter end) everyone had the most absolute confidence in a speedy relief. General Townshend was, of course, always extremely, perhaps excessively, optimistic; and I think that even the pessimists could not threaten us with a later date than the end of January. Calculating on what we were told from time to time of the situation, we fully made up our minds that we should be relieved, if not by Christmas Day, at any rate within the following week or so. This particular time of year, we argued, being cold and still dry, was the very best for a force to operate in this country; the 6th Division had succeeded in advancing, even in September, over this very bit of country; our force at Kut was undeniably holding up a considerable enemy force, and thus giving material help to the relief column, even before the time came for us to sally out and join hands with them. In those days no one ever dreamed of our being so reduced in numbers and in strength of body as to make a sally all but impossible. Food and ammunition were then ample, though always regarded as precious and non-renewable. The hospitals, from the fact that a base depot for medical stores had been established at Kut when we advanced on Ctesiphon, were well supplied; and any drugs, etc., that did run out before the end were replenished by aeroplanes.

As Christmas approached, the Turks kept pushing their trenches nearer on the north, and both they and ourselves became a bit enterprising. We raided their advanced trenches one night, and brought back some Arabs who were digging for them; while just before Christmas their shelling grew more intense. All this pointed to their making a big effort soon, but we buoyed ourselves up with the thought that the relief force could not be very much longer.

On the night of the 23rd/24th there was almost continuous firing, and on the morning of Christmas Eve the enemy delivered an assault on the Fort. The Regiment moved up there and took over one side, but the Turks did not assault again until nightfall. They kept up intermittent shelling, however, during the day, and Naylor (S Company Commander) was wounded in the face by shrapnel. From about dusk they assaulted and bombed all through the night, principally at a point just to the right of Q Company. The Turks managed to obtain a footing in one bastion of the Fort, and against them a hasty barricade, of bhoosa bales, store-tins, flour-bags, and anything that came handy, was run up. The enemy was on one side and our people on the other, and a bombing match went on here during most of the night, all the heavier casualties of Christmas occurring at this spot.

Towards daybreak the Turks gave it up as a bad job, and began to withdraw, when, from where I was, we were able to fire at them as they retired round the bastion. Then came daylight, and we were able to take stock of our position. Turkish dead and seriously wounded lay thick right up to our trenches. We made an attempt to bring them in; but the Turks, from their trenches barely a hundred yards away, opened a heavy rifle-fire on us until we desisted. Our men succeeded in passing out water and food to them, but many died within a few yards of us, without our being able to do anything for them. For some reason the Turks themselves would not succour their wounded, as we saw some of them crawl back and get right on to their parapet, only to remain there for want of a helping hand from their friends. Presumably, they were afraid that we would fire on them if they showed themselves, though, of course, we had no such intention. We lost a number of men killed and wounded, and Mellor (commanding R Company) was seriously wounded in the wrist by a bomb. The few Turks captured were sent down to Kut, and as the morning advanced we began to feel confident that the enemy had more or less shot his bolt.

This was Christmas Day, though it did not seem much like it, except that the afternoon was quite peaceful and quiet— in fact, almost uncannily so. By the evening, however, although we had no more assaults, there was a certain amount of liveliness—rifles, machine-guns, and artillery, the latter firing at almost regular intervals throughout the night. After dark another effort to bring in the wretched Turkish wounded was made, and with considerable success. We got in all except those who could not be moved without a stretcher, and the use of stretchers was out of the question, as it was impossible to take them out and back even through the ruined walls of the Fort. Besides the wounded, our search parties brought in a certain number of unwounded and slightly wounded Turks, who were evidently anxious to surrender.

That night there was a lot of work to be done in the matter of reorganizing our lines and repairing the damage done by the bombardment and assault, and the work took days to finish really satisfactorily. The mud walls had either great holes or huge breaches, and piles of debris lay about in every direction. Roofing timbers, corrugated iron, equipment, stores, and everything else were lying buried under heaps of bricks and rubbish, thus completely blocking the old trenches, which in many parts were entirely obliterated. The most difficult task of all was getting out fresh barbed wire, practically the whole of the old wire having been destroyed by the bombardment. On the northern front in most places the enemy's trenches varied in distance from ours from eighty yards to only about fifteen yards (at the advanced saphead), and in these circumstances it was no easy matter to wire our front. At the worst places we made "spiders," and pushed them out over the parapet, but elsewhere there was nothing for it but to crawl out and use a muffled mallet as best we could. The days and nights now were all much the same—by day, deepening old trenches, clearing out after rain, or digging new trenches ; by night, completing work which could not be done with safety in daylight. There was now always a Regimental Officer on watch all night, his duty being, in addition to looking after his own company, to walk up and down the whole regimental line, with a Very pistol in his hand, ready to let off coloured lights or rockets. There were four of us available for this duty, and it was carried out in four-hour watches. As we were at work all day until late in the evening, this was rather a strain, but when Naylor returned from hospital we were able to get one night in four off duty, though frequently a very disturbed night, and always a short one, as we stood to arms each morning at 5.30.

The rough sketch which I have made shows approximately how the defences were shaping themselves by the end of the year.

Sketch Map No. 4.

Of course, there were a great many more minor trenches which I have been unable to put in, especially on the extreme west, which I never had an opportunity of visiting before the floods washed all the defences away.

The week following Christmas was somewhat tense, but in reality uneventful. The Turks were still as close as ever, and at first their sniping rather worried us but we soon got the upper hand at that game. The nights were sometimes a bit noisy, but by the end of the week we came to the conclusion that they were not intending another big assault, for we observed their columns behind their trenches moving in the distance across the desert in the direction of the Es Sinn positions, from which they had been turned out just three months before. The people in the Fort observation tower used to make careful notes of all these movements, and a confidential diary of what had been going on was sent round to us each evening. The rough road along which these Turkish troops moved from west to east was just within distant artillery range, but owing to the necessity of conserving ammunition, and to the length of the range, our guns did not fire at them often. Once or twice we tried rifle and machine-gun fire from the front line, but it was quite valueless. While these movements were in progress, and just after they ceased, the Turks sniped and shelled rather more vigorously than usual, presumably in order to show us that they were still in strength opposite to us.

The next excitement was the appearance of two aeroplanes (German Fokkers), which were very good, giving us any amount of trouble right to the end, and never being hit. Soon afterwards we had the cheering sight of our own machines coming up from down-stream, but they never managed to time their flight so as to meet and settle matters with the Fokkers.

The Turkish prisoners taken at Ctesiphon, as well as our wounded, had been evacuated to Basra, and on the 5th December the Cavalry Brigade and the transport animals were sent down to Ali-al-Gharbi. Aware that he could expect no relief until fresh troops should arrive from overseas, and aware also that the Turks, in increased numbers, were hemming him in, Townshend prepared to stand a siege. The place had practically no defences, for although during the absence of the 6th Division up river a scheme of defence was mooted, for one reason or another little or nothing was done. There had been built a so-called fort consisting of mud walls, useless against artillery, and three or four equally useless block-houses, joined by a barbed-wire cattle fence, stretching across the neck of the river's loop. All this had to be altered, and henceforward strenuous digging went on day and night. Fortunately the enemy gave us time, for though he drew gradually nearer on the north, he did not force an attack.

By the 7th December, however, Kut was completely invested, and from that time only wireless messages told the outside world what was happening to the besieged garrison. From these it was learned that, on the 8th December, Nur-ud-Din went through the formality of calling on General Townshend to surrender; on the 9th drove in the British detached post on the right bank of the river, and then, for several days, bombarded Kut from all sides, and pushed infantry attacks against the northern defences, to be repulsed with heavy losses on each occasion. After the 12th December the enemy abandoned these costly attacks, and settled down to a bombardment and sapping operations, the particular objective being the Fort at the north-east corner of the defensive line. Between the 14th and 18th successful sorties were made by the garrison, and it was not until: the night of the 23rd/24th December that the Turks again made any strenuous effort to renew the assault.

On that night and the following day the Fort was subjected to heavy concentrated fire, with the result that the parapet was breached, and the Turks effected an entry. The success, however, was only momentary, for a counter-attack immediately ejected them, and they left behind them some 200 dead.

Not content with this rebuff, the enemy returned to the attack a little later, and at midnight (24th/25th) again entered the Fort. "The enemy," said General Townshend, in his wireless report, "effected a lodgment in the northern bastion, were ejected, came on again, and occupied the bastion. The garrison (Oxford Light Infantry and 103rd Mahrattas) held on to an entrenchment, and were reinforced by the 48th Pioneers and the Norfolk Regiment. The enemy vacated the bastion on Christmas morning, and retired into trenches from 400 to 900 yards in the rear, although the attack had been made from trenches only about 100 yards from the breach. The rest of Christmas Day passed quietly. The fort garrison, in excellent spirits, reoccupied the bastion.

The enemy's casualties estimated at about 700, our own at 190 killed and wounded."

This was the last attack made on Kut, for Nur-ud-Din, assured by the German Marshal, Yon. der Goltz, of the impossibility of the garrison breaking out, left sufficient troops to contain it, and on the 28th December commenced moving strong forces down to Sheikh Saad, in order to frustrate any attempt on the part of the British to relieve the beleaguered garrison.

During the four long months which followed the "gallant 6th Division," locked up securely, withstood with patience and resolution all the rigours of a siege— wondering often if the floods would prove a greater enemy than the Turks, yet hoping always that relief would come at any moment. Time after time were they disappointed, for the Turks, reinforced frequently, beat back every attempt of the relieving force to hew its way through, until at the end of April 1916 Kut was starved into surrender, and the 6th Division made prisoners of war.

The following description of the retirement from Ctesiphon and the Siege of Kut-el-Amara was written in 1916, after his exchange as a prisoner of war, by Lieut. G. L. Heawood, 2/4th Wiltshire Regiment, who was attached to the 1st Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, and commanded Q Company from the 24th November 1915 until the surrender of Kut. We give his account first, because the time at which it was written down was nearest to the events recorded. The other accounts, also written from memory, were put together at somewhat later times.

Lieut. Heawood's Narrative.

On the evening of the 23rd November(Unfortunately, I was not present during the attack on the 22nd, as I was at Lajj with the boats, and could not get up to Ctesiphon until the battery wagons came down to refill.—G. L. H,) the British force bivouacked at a spot about the centre of what had been the Turkish first line. The spot was called High Wall, from the fact that there was a high and thick wall there forming three sides of a square, which the Turks had improved into a redoubt. Within the redoubt I remember seeing a very ancient mortar, on which there were some curious figures and letters. Ctesiphon Arch stood out about a mile away, and, with its surroundings, presented a most picturesque scene.

The Turks had retired for at least two miles, but there were still Arab horsemen about, and these began to hover around us as dusk came on. All that night and the following day our wounded (of which there were immense numbers) were collected and evacuated to Lajj, our base camp by the river, some eleven miles in rear.

Early on the morning of the 25th there was some slight trouble with Arabs, but a few shells from our guns dispersed them, and for the rest of the day we settled down to digging additional trenches. From the top of the High Wall one obtained a good view of the country to the north, and during the afternoon we could see in the distance large Turkish forces moving away towards the east. So far we subordinates knew nothing of the plans for the future, but at 6 p.m. orders were issued for a move in an hour's time, and all available carts with the force were redistributed to units. Anything that could not be taken with us was to be buried or destroyed, and the usual night-march regulations were to be stringently enforced—absolute silence, and no lights. By 7 p.m. we were on the move, and after some delay in getting units into their proper order of march, we settled down to our trek back to Lajj, where we eventually arrived at about midnight. Then followed the wearisome process of telling off the troops to their respective bivouacs, which Avas no easy matter in the dark, and was made worse by a heavy downpour of rain. Happily the cooks, who had marched ahead, had tea ready for us, and, better still, the blankets had not been unpacked before the rain came on, .so only the outer ones were wet. Warm tea and warm blankets helped us a lot. The Regiment bivouacked for the night about the north-east corner of the camp, but it was well on into the early hours of the morning before we had settled down and posted sentries on our part of the perimeter.

The 26th was spent in what seemed to us rather an aimless sort of way. Schemes for outposts were being got out; boats of wounded sent down the river; our cavalry out keeping touch with the enemy cavalry; but no one quite knew what was going to be done next. Late in the afternoon we took up a line of outposts, my company furnishing three piquets, so we had little rest that night. Next morning, however, we were relieved, and the cavalry and small day-groups of infantry kept a look-out. At midday (27th) we received our orders to march, and the advance parties got off about 2 p.m. We qurselves were among the last to move, and did not clear the camp until quite near dusk. Our cavalry still remained away on our flank and rear, and aeroplanes had been on the move up to the last moment; moreover, to further induce the Turks to believe that we were staying at Lajj, a considerable number of tents were left standing. The nighfs march' was a particularly dreary one, although, as matters turned out, it proved quite successful. Many things contributed to make it dreary : we had not been told how far it was proposed to go; we did not know what excitements there might be in store for us on the way; it was a densely dark night, the wind was getting up, and the clouds of the rainy season gathering round; halts were somewhat frequent; and once or twice we were sniped at by Arabs, in spite of our flank guards. When at last day broke, matters became pleasanter, and at about 8 a.m. (28th) we approached Aziziyeh, where we had spent a month in camp on our way up to Ctesiphon. General Townshend and his Staff stood at the entrance to the camp, and saw every regiment march in, and by 9 a.m. we had settled down in bivouac, and were glad of breakfast. We must have covered a very good 25 miles since leaving Lajj, and the fatigue of the march was immensely increased by the slow pace and the many unavoidable halts.

Most of that day and the following night we rested, and the 29th was spent chiefly in refitting the men and trying to evacuate stores from Aziziyeh. Much stuff had, of course, to be abandoned, as most of the boats had gone down-stream with wounded; but a certain amount was floated down the river, while things that could not be saved were destroyed.

On the morning of the 30th we made a very early start, all arrangements having been made the day before. Apparently there was an impression that we were becoming tolerably safe from a close pursuit; also, what with the fighting at Ctesiphon and the long night march to Aziziyeh, everyone was more or less tired out. Whether these were the reasons or not, I cannot say ; but we were given a march of only 8 miles or so, and went into bivouac on the river bank, about a mile beyond some mounds marked on our map as Um-al-Tumman (Umm-ath-Thumma), which soon after came to be known as "Ummle-Tummle," and, finally, as "Rumble-Tumble," but all this was after it had become identified with the most adventurous part of the retirement. Soon after we got in we started digging trenches round the camp, and others in the camp for shelter, and by nightfall everything was looking fairly bright. Ample food had been brought with us from Aziziyeh, and I remember that at "drumming-lip" that evening my company had any amount of bacon frying. There was also plenty of straw and hay close to our lines, which were in part of a deserted Arab village; so we had soft beds. Besides all this, we had received reinforcements before leaving Aziziyeh—half a battalion of the West Kents and the 14th Hussars, freshly arrived in the country—a welcome addition to the Indian Cavalry. So far there was every promise of our getting down to Kut by easy stages, but it was not to be, for just as we were settling down to a comfortable night, we heard the boom of a gun, and presently the distant rattle of musketry, followed by the bursting of a shell, evidently fired in our direction. This was the end of our comfortable night, for we were ordered into the trenches forthwith, and though nothing particular happened, spasmodic shelling went on throughout the night. Instead of getting away next day, we had to remain, as some of the steamers had run aground, and the enemy was reported to be coming down the banks in force.

Almost before daylight on the 1st December the transport moved out of camp towards the south. The 17th Brigade had been told off as rearguard, and I found myself extending my company out along the northern part of the camp, and watching masses of our cavalry moving away eastward into the desert in the grey light of early morning. The column was barely clear of the camp before it became evident that we were going to be attacked; bullets began to fall, but not very well aimed, although, as a matter of fact, a man of my company was wounded.

After a while things became more lively, and we fell back a little on to our two support companies, who were lining a magnificent nullah about 100 yards behind us. The companies of the other regiments fell back also, and soon the whole of the 43rd were extended along this nullah, covering the retirement of the other units. Meanwhile, our artillery was doing good work in keeping the enemy back, and we remained in position until his skirmishers had come within a few hundred yards, when we withdrew through the 22nd Punjabis, who were lined out ready to cover our withdrawal to another nullah 120 yards or so behind. These alternate retirements continued for some distance across some very open desert,,the 22nd Punjabis, with whom we worked all through, behaving splendidly. The other two regiments on our right retired in a similar: manner, and, with each retirement, we gradually increased the distance between ourselves and the Turks. The enemy's shrapnel fire! was rather trying, as it burst very accurately; but;we were remarkably fortunate in casualties, having very few, and being able to get nearly all the wounded back to the field ambulance.

After crossing the open stretch of desert we rejoined our guns, and held on while they limbered up and got away to a fresh position in rear. This manoeuvre—first the guns retiring and then ourselves —went on for some little time, and, whenever we had to wait for the guns to get back, the Turks pushed in closer, though we left them behind again whenever we retired. At last we so increased the distance, that it became safe for us to retire in artillery formation, but even then we had occasionally to form a firing line in a nullah. So the day went on, and we were beginning to think that there would be no end to it, when, much to our relief, we were reinforced by the 30th Brigade, who had been sent on two nights before in advance of the main body to Kut, but had been ordered back when the trouble began. They now co-operated with our Brigade, and before very long we reached a bend in the river, where we halted for about half an hour, while our wounded were put on a boat and sent off.

Meanwhile, much had been going on on the river itself, though, of course, unknown to us, fighting our way across country. It appears that the boats remjaining at Aziziyeh, in order to accompany us down stream, weighed anchor at daylight. They could not start earlier, owing to the particularly bad sand-banks which infest the reach of the river hereabouts, making rapid progress even by day quite out of the question. As it was, we lost at least two barges here—one an aeroplane barge, and the other an ordnance one. On the latter, most unfortunately for us, were all our regimental orderly-room papers and documents—a most serious loss, which produced endless work after reaching Kut, as all company papers had gone, including pay-sheets, nominal-rolls, etc. The two gunboats seem to have hung on too long, and the "Firefly" was knocked out by a shell through her boiler, after her commander had been wounded. The "Comet" stood by to help her, and took off her crew, but almost immediately ran aground, and soon shared the fate of the "Firefly," though not before the wounded had been transferred to a barge and towed away by a small tug. The crews got ashore and eventually joined our column,-amongst them being Colour-Sergeant H. Gibbs, the Machine-gun Sergeant of the "Firefly," who had been lent from the Regiment for this duty, and who afterwards became C.-Q.-M.-S. of Q Company.

However, to return to the river-bend at which we had halted. It was obviously not a spot at which to make a long stay, much as we desired a good rest, and soon we were on the road again, the 17th Brigade still in rear, though now more or less closed up, as our cavalry were protecting our flanks and rear. The track now lay inland across the desert, which, except for scattered low scrub bushes, was bare and dry. All the regimental horses (even the Colonel's) had been sent on with the transport, so everyone had to foot it. Occasionally a transport-cart, or one of the three motorcars which were in the country, turned back to pick up stragglers; for, as the day advanced, it became more and more difficult to keep the men going, in spite of their knowledge that if they dropped out they would have a short shrift from the merciless Arabs. I think that the poor little Gurkhas (belonging to the 30th Brigade) suffered most, as they are not built for forced marching, and they had had more than their share since they had been turned back to help us in the morning. Still, I may say here that they stuck it heroically, and the 30th Brigade lost not a single man taken prisoner all the way back to Kut.

Later, we were encouraged by the announcement that, after seven more miles, we should halt on the river bank, get water, and rest for three hours. Our spirits revived, and, after a rather weary drag, we found ourselves close in to the river again, near a clump of trees. Mules were off-loaded, water-drawers detailed, and equipment loosened. But fate was against us once more. Before the water-parties had reached the stream there was a rattle of musketry, and, though the offenders were only Arabs, our machine-guns were unable to suppress the firing. Our prospect of water and a rest had vanished, and within half an hour we were off again, on another slow night march. The night was black, and it was impossible to see men at any distance in front of one; consequently the pace averaged barely two miles an hour. Obstacles, such as dry nullahs or clumps of low scrub, constantly caused checks to the column, and it was no easy matter to keep even one's company closed up, especially as the men were more or less done up and only half awake. In this way we plodded slowly on until, at about 2 a.m. (2nd December), we saw bivouac fires ahead, and were told that we might lie down, as we were, in column of route. Food was not forthcoming, as the transport was a long way ahead; water, we were promised we should get soon after we started again. It was a bitter night, with a strong north wind, and our cotton uniform did not help us to keep out the cold. Three of us tried to make a fire, but it would not burn, so we gave up the idea, and sat round and dozed—but not for long, for soon the order came to be ready to move in five minutes. The mules were loaded up, and we were off again.

Soon after starting we passed over a brick bridge which spanned a large dry watercourse, and this the sappers blew up as soon as the column was; clear, thereby creating a considerable obstacle to the immediate passage of enemy guns. We now moved across the desert in parallel columns of companies, with the cavalry covering our inland flank and our rear. For breakfast the men were allowed to eat their emergency rations, but the promise of water remained only a promise. It grew harder and harder to keep the men going, as they were quite ready to fall out, and prepared to risk everything for a rest and a drink of water; but the N.C.O.'s were magnificent, and it was due to them that we managed to get along. Twice we approached the river and had to go on, but at last we actually halted at a watering-place, and the water-parties got down to the river bank. Even then it was questionable whether we should get our drink, as Arabs began sniping from the opposite bank. Oar machine-guns were soon at work, however, sweeping all visible ground, and the 18-pounders unlimbered and gave them a few well directed shells — things which the Arab dislikes intensely,

We had a rest of nearly three hours, and the men had time to "drum-up," i.e., make cocoa and boil up their emergency rations in their mess-tins. When we got under way again, we had about 9 miles to go to reach the outskirts of Kut, but dusk came on before we saw any signs of the place. The cavalry were drawn in, and we put out flank guards; then carts came out, some to pick up the most footsore of the tired men, and others with food—a somewhat scanty allowance, but most welcome. We waited for some time, and wondered why, until we learned that we would not enter the place until daylight, when we could go right in, and take up our allotted quarters without any trouble.

Quite early next morning (3rd December) we covered the last two miles, and, marching straight to our camping-ground, had a good hot breakfast, rolled ourselves up in our blankets, and slept until midday.

Of the next few weeks the chief memory that remains is one of digging. We seem to have dug all day and every day—in the glare of the sun, in the darkness of the night, and in the moonlight. We commenced these labours on our first afternoon, for although we were not technically surrounded for another three or four days, we prepared for the siege which was known to be inevitable. The ships with our wounded and the Turkish prisoners were all sent away down river, only the "Sumana," with one or two tugs and the 4.7-inch gun barges, remaining at Kut. Then the cavalry (less one squadron) were dispatched down to Ali-al-Gharbi, and on the 7th December we were invested. "I will now give a description of Kut and the defences when the siege commenced.

The town lies at the apex or toe of a horse-shoe bend of the river, and contains some very respectable buildings, including -a covered-in bazaar, a caravanserai, the Sheikh's house, two mosques (one with a fine minaret), and other large public and private buildings. These are all built of hard, mud bricks, have several stories, and generally a courtyard in the centre, with much woodwork, some of it, quaintly carved. There are palm gardens scattered about the town, and large palm groves at either end, while on the outskirts to the north-east are some old brick-kilns, solidly built, in the shape of small, squat towers, with broad and hollow bases' These eventually were much used by the artillery. Opposite the town and on the other side of the Tigris, the Shatt-el-Hai flows out southwards to the Euphrates, though it dries up in the summer South-west of Kut, and in the angle formed by the Tigris and the Hai, stands a small village (whose name I never saw in writing, but pronounced something like Woolpress), close to which was an old liquorice factory, with some liquorice stacks a little farther west.

North-east of the Hai, and two or three miles down the right bank of the Tigris, is another small Arab village, with more liquorice stacks, and close by there was a Turkish bridge of boats (by means of which the telegraph wires crossed the river), which,, of course, we removed. Across the neck of the river bend (i e across the heel of the horse-shoe), a line of five block-houses with barbed wire in the intervals and a large mud fort at the north-east end, had been put up after our original advance from Kut as a protection against Arab raiders. That was all we found by way of defences when we commenced preparations for the siege. In one respect we were certainly fortunate : large stores of grain were found in and about the town, and, of course, materially lengthened the siege.

The above defence arrangements might have been all very well against Arabs, but as the block-houses had nothing more than loop-holed walls above ground-level, they were quite useless against Turks with artillery; they were demolished, and a line of strong redoubts substituted. The Fort, however, was left standing as it was so big that to get rid of it would have entailed too much work and a waste of explosives; but it was strengthened considerably with dug-outs, trenches, and overhead cover. As a matter of fact it proved very useful, though attracting a good deal of the enemy's attention.

On the 4th December General Townshend issued the following :—-

Special order. Proclamation to the Troops.

" I intend to defend Kut-al-Amarah, and not to retire any further; reinforcements are beginning to be sent up from Basra to relieve us. The honour of our Mother Country and the Empire demands that we all work heart and soul in the defence of this place. We must dig in deep, and dig in quickly, and then the enemy's shells will do little damage. We have ample food and ammunition, but Commanding Officers must husband the ammunition, and not throw it away uselessly.

"The way you have managed to retire some 80 or- 90 miles under the very noses of the Turks is nothing short of splendid, and speaks eloquently for the courage and discipline of this force."

(This Order and General Townshend's Communiques (printed further on) were copied into a notebook by an officer in Kut, who was subequently exchanged as a prisoner of war. He succeeded in bringing his notebook away with him, and, on reaching India, had type-written copies made of the entries,—-G, L. H,)

On our first afternoon the Regiment dug trenches for about four hours along the river bank between the Fort and the brick kilns. That is to say, we entrenched our bivouac ground, and that night we only found river piquets, the remainder of us sleeping in the new trenches, where we were secure from sniping from the opposite bank of the river. Next morning we completed these trenches and added some improvements; but this was not to be our permanent home, for in the evening another regiment relieved us, and we dropped back to two dry watercourses, more or less at right angles to our former trenches. This new line faced north, with its right adjoining the southern end of the previous line, and its left on the track from the town to the Fort. The 63rd Battery R.F.A. dug themselves in on our left.

During the early part of this night we improved and made habitable these two parallel watercourses, and subsequently we improved them still further, as they became our headquarters until the end of the siege. In the front line there were three companies, R on the left, P on the right, and Q in the centre, while S Company was in the rear watercourse, or trench, behind Q and P Companies. The trenches were eventually roofed over, as were also the various dug-outs (between the two lines of trenches), such as the mess, dressing-station, orderly-room, quartermaster's stores, men's cookhouse, Company Officers' quarters, etc. Nominally, this was our bivouac ground, and it was the place to which we always came back, though we really seldom occupied it, as we were generally digging, or working, or holding trenches elsewhere. At this time the nights were very cold: bitter north-west winds, with an occasional frost; and the days also were quite chilly. .

The next bit of work we commenced was a communication trench to the Fort, while other regiments dug trenches along the barbed wire on the old block-house line. But that was before we were cut off from the outside world. From the 7th December business began in earnest; most movements above ground had to be done at the double, and all digging was got down a rough three feet by night, earth being thrown up on whichever side seemed most exposed, and then completed by day. The Turks started in by drenching the place with shells; I do not know how many hundred they fired at us in these early days; and a little later, when they got closer, they swept all the flat ground with machine-gun fire.

I think it was on the night of the 7th/8th that the enemy made his first attack—in actual fact more like a reconnaissance in force. He made for the Fort and adjacent trenches, and three of our companies went up and manned the trenches which we had originally dug from the Fort southwards along the river. A few men of the Regiment were wounded, but the attack soon dwindled, and we returned to our bivouac quite early in the night. It must have been the next day or the day after that an attempt was made, before the Turks closed in on the east, to establish a bridgehead post on the right bank of the river opposite the brick-kilns. The bridge of boats was towed to this point in the early morning, and a small force (from the 30th Brigade) was put across, while we assisted by lining the river bank just south-east of our bivouac. The attempt, however, was a failure owing to the resistance offered and the fire which the Turks kept up on the bridge. The withdrawal of the party was effected, and the bridge was partly recovered and partly demolished. After this the only post which we had on the right bank of the river was round the place which I write "Woolpress " in trenches across the angle between the Hai and the Tigris.

From this time onwards the Turks were continually advancing and making preliminary attacks on our northern front, while we used to man our trenches, generally for 48 hours in and 24 hours out, though the latter period was usually harder than the former, as it was mainly spent in digging communication trenches and making our portion of the inner defences, or what was known as "Middle Line." The Turks made no actual assault during these early weeks, but they drew closer in, and we had some very anxious nights, especially on one occasion when we got a regular alarm of a night attack and the artillery fired star shells, etc., for some time. During the daytime they occupied themselves with shelling our various defences and the town, sweeping our trenches repeatedly with machine-gun fire, and sniping with the greatest accuracy. It was, I think, on December 11th that poor Brown, who commanded P Company, was killed by a sniper's bullet in the head, and we lost several men in a similar way—happily, all quite instantaneous. But in the very narrowed circle within which we were living, losses like these were felt deeply, and Brown had always been the most lively member of the mess. We suffered also from shrapnel, for the enemy, being all round us, was able to fire into our rear from across the river.

Throughout December (and, indeed, almost up to the bitter end) everyone had the most absolute confidence in a speedy relief. General Townshend was, of course, always extremely, perhaps excessively, optimistic; and I think that even the pessimists could not threaten us with a later date than the end of January. Calculating on what we were told from time to time of the situation, we fully made up our minds that we should be relieved, if not by Christmas Day, at any rate within the following week or so. This particular time of year, we argued, being cold and still dry, was the very best for a force to operate in this country; the 6th Division had succeeded in advancing, even in September, over this very bit of country; our force at Kut was undeniably holding up a considerable enemy force, and thus giving material help to the relief column, even before the time came for us to sally out and join hands with them. In those days no one ever dreamed of our being so reduced in numbers and in strength of body as to make a sally all but impossible. Food and ammunition were then ample, though always regarded as precious and non-renewable. The hospitals, from the fact that a base depot for medical stores had been established at Kut when we advanced on Ctesiphon, were well supplied; and any drugs, etc., that did run out before the end were replenished by aeroplanes.

As Christmas approached, the Turks kept pushing their trenches nearer on the north, and both they and ourselves became a bit enterprising. We raided their advanced trenches one night, and brought back some Arabs who were digging for them; while just before Christmas their shelling grew more intense. All this pointed to their making a big effort soon, but we buoyed ourselves up with the thought that the relief force could not be very much longer.